"A school and not an asylum"

Gospel music pioneer Arizona Dranes learned to sing and play at the Black blind school in Austin

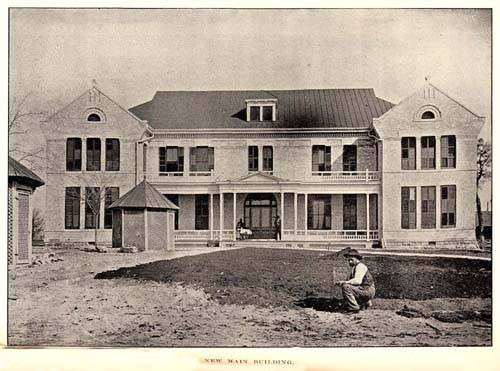

When the Institute for Deaf, Dumb and Blind Colored Youth opened on Oct. 17, 1887, with 17 pupils and two teachers at 4101 Bull Creek Road, it was hailed by the Texas Legislature as proof that the state was compassionate to its least fortunate.

Founded with a $50,000 appropriation from the Texas Legislature under Gov. Lawrence “Sul” Ross to buy 108 acres and build a school and dormitories about two and a half miles northwest of the capitol, the school became an area of research to me in 2007, when it was discovered that gospel music pioneer Arizona Dranes (1889- 1963) learned to play the piano there. A barrelhouse thumper, who made what are considered the first true gospel recordings in 1926 in Chicago, Dranes attended the institute from ages 7 to 23.

Born in Sherman, 260 miles to the north, Dranes was almost certainly sponsored by Sherman teacher J.W. McKinney, who taught at the Frederick Douglass School, where Dranes would’ve attended if she wasn’t blind. Also the head of the black Masonic Lodge of Texas, McKinney spoke at the Austin blind school’s 1902 commencement (when Dranes was 13), urging students to make full use of whatever gifts God had given. He ended his speech with a downplay of the era’s racism.

“The fact that you are here, my friends, surrounded by all the comforts and facilities at public expense, these spacious buildings and beautiful grounds furnished for you, gives lie to (the belief that) whites have no regard for the rights of blacks,” he said.

Head of the music department at the blind school in 1897 and 1898 was pianist Maud Cuney, a former fiancee of W.E.B. Du Bois, who went on to become a noted musicologist under her married name Cuney-Hare. She was one of the first to explore the African roots of American music, and published the first book of Creole songs in 1921. Her landmark 1936 book Negro Musicians and Their Music was, sadly, released months after she died of cancer at age 61.

Joining the faculty in 1900 was mixed media artist Mattie B. White, who taught deaf students to paint and embroider and blind students to crochet and weave baskets and rugs. Also a African American historian, she led the drive to designate Emancipation Park in East Austin and helped popularize the Juneteenth celebration. White taught at the deaf and blind school for 40 years.

Curriculum records kept at the Texas State Library show that Dranes was no musical primitive, as previously believed by biographers, but classically trained in voice and piano at the school. Playing music was considered a good way for the blind to make a living, in addition to broom making and basket weaving.

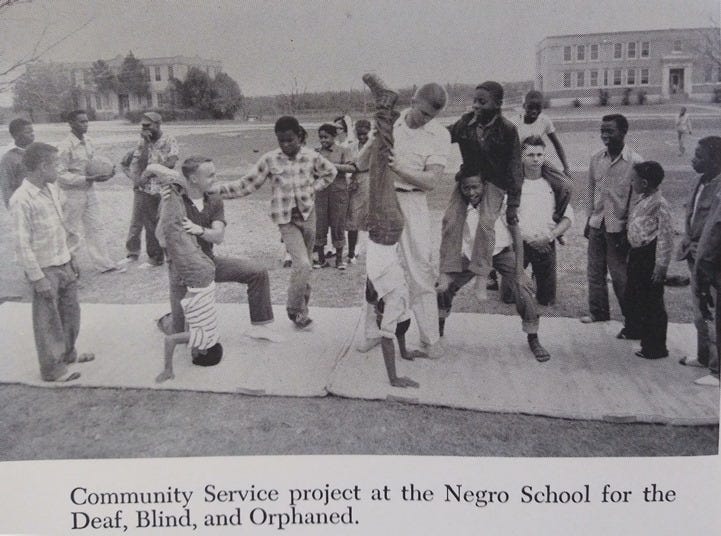

In 1943, the Institute combined with the Colored Orphans Home and was renamed Texas Blind, Deaf and Orphans School. It remained on Bull Creek Road until 1961, when the school moved to 601 Airport Boulevard, the former location of the Montopolis Drive In movie theater.

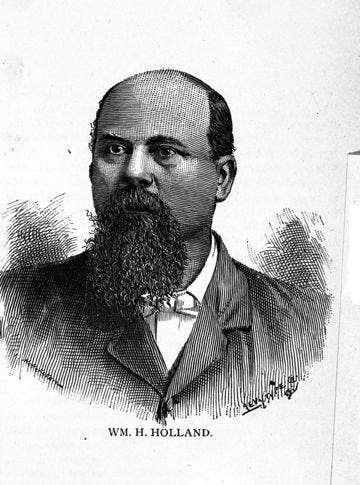

The impetus behind the school’s creation in 1887 was William H. Holland, a state representative born into slavery near Marshall in 1841. Holland’s freedom was paid for in the 1850s by his white father Captain Bird Holland, a hero of the Mexican War, who would later become the Texas secretary of state. The Captain sent William and his other sons from slaves, Milton and James, to Ohio to be educated.

During the Civil War, the sons fought on the side of the Union, while their father was an officer in the Confederate Army, killed in action in 1864 at the battle of Mansfield, Louisiana.

Elected to the Texas House of Representatives in 1876 from Waller County, public education of all Texans was Holland’s dominant platform. Citing an amendment to the state’s constitution that “Separate schools shall be provided for the white and colored children, and impartial provisions shall be made for both,” Holland challenged that since whites had Texas A&M, a similar college should be provided for blacks. As a consequence, the Fifteenth Legislature established “Alta Vista Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas for Colored Youth” in late 1876. Holland is known as “The Father of Prairie View A&M,” which is what the school’s name was changed to a few years later.

Holland was superintendent of the Institute of Deaf, Dumb and Blind Colored Youths from 1887- 1897, then was reappointed from 1904 until his death in 1907.

In another interesting Dranes connection to Austin, she was converted to Pentecostalism in 1922- at age 33 – by preacher J. Austin Love, who grew up the son of a laborer and teacher at 808 E. 11th St. near where Franklin’s Barbecue is today. Reverend Love met Dranes in Wichita Falls, where he founded the town’s first Church of God In Christ, in 1922. When the preacher was called to Fort Worth the next year to open the White Street Holiness Church, he took his prized piano-playing parishioner Dranes, whose musical career was launched in Fort Worth.

She’s known as the inventor of “the gospel beat,” putting secular styles to spiritual music. But at the blind school in Austin she was taught classical music, bringing tecnique to the “tongue people” on Pentecostalism.

Here’s Arizona Dranes doing “I Shall Wear a Crown”

My chapter on Dranes in Ghost Notes: Pioneering Spirits of Texas Music

I'm fascinated by her story as told by Cocoran and Timothy Dodge. Read both of the books written by them. For her time in Austin to only be uncovered in 2007, some 90 years after her time in Austin, speaks to the many records that remain un-discovered. Add to this the great stories of William Holland (and his bothers), as well as many others whose lives crossed paths with Arizona Dranes speaks volumes to the struggles and compassions of the times. I first got into her life and William Holand through research into the Institute on Bull Creek Road after the State sold the land. I'd also read that William Holland was the first black Travis County Commissioner - in the 1870's. Truly remarkable stories. Thanks Michael.

Thank you.