Austin Music Is a Scene: the Setup

Preface to history book coming Spring 2024 (hopefully)

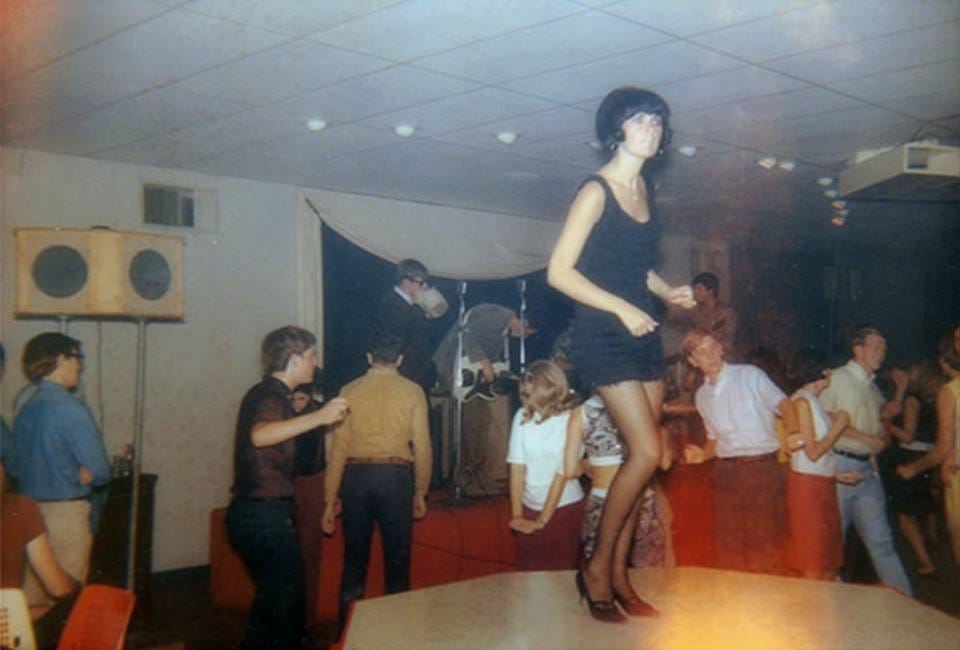

PREFACE: WELCOME TO CLUBLAND PARADISE

by Michael Corcoran

Just as a scene is not only the music, clubs are much more than stages and walls. They are the folks who work there and go there and play there. I knew these were my people the night I arrived at age twenty-eight. After I found Austin, I had to chuckle inside when someone called Hawaii paradise.

The natural beauty of my home state was nothing compared to the former dry cleaners, pizza parlors, and used furniture stores where I saw Lou Ann Barton, Little Joe y la Familia, the Offenders, Albert Collins, the Commandos, Dino Lee, and Herman the German in my first couple weeks in town.

Forget the white sand and ocean blue, my favorite Beach was on the north shore of the University of Texas, where Daniel Johnston played between acts for five dollars a song—good money for a McDonald’s janitor.

I loved how the scenes intersected, how you’d see some of the same people at Voltaire’s punk basement as you would at a LeRoi Brothers show. Everyone seemed to know (and secretly envy) everyone else, which made Austin perfect for the kind of music/gossip column I was made for. That I was the ultimate outsider (“He’s from fucking Hawaii!”- Charlie Sexton in Creem, 1986), writing as an insider, was a joke many didn’t care for.

My acerbic “Don’t You Start Me Talking” column in the Austin Chronicle from 1985-88 made me some enemies—I was voted “The Worst Thing to Happen to Austin Music” in 1986 by the readers of the Chron— but everybody read it. I was clickbait before the click.

The way I saw it, Austin was a city full of itself (was?), and it was my job to bring it down a few pegs. “Every overinflated balloon needs a prick” is how Brian Beattie of Glass Eye described my role. But Austin wasn’t wrong about itself. This is the only place I had to move away from, in 1988, because the good times were getting out of hand.

This is a city people have flocked to since the ‘60s for the quality of stimulation, which is the quality of life. The Austin icebreaker: “What boring town are you from?” The Austin cliché: “You got here too late.” Nah, I’d counter, you peaked too soon. I couldn’t imagine any time and place being more alive than this Clubland Paradise in the ’80s.

The present was so good I had little interest in the past, aggressively ignoring every three-name act that rated a chapter in Jan Reid’s The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock (1974).

When I was a young writer, I didn’t really know anything so I relied on a fearless attitude to get folks to read me. But with experience and research comes knowledge that can entertain in a more satisfying way. In the past few years, I’ve become consumed with history I never thought much about before.

When old timers taunt new arrivals with tales of the city’s glorious past, they lay a cattle guard to that history. But the lucky ones are actually those who just got here. (“Huh? You must also love those assholes that try to squeeze into a full elevator.”) There’s no sad sense of UBT—Useta Be There—for those who’ve always had to dial 512 for local calls. There’s not a CVS in town that can make them cry.

Yes, it used to be better here. So what? Living in this city is like sex, in that what happened in the past has only sentimental value, which when it comes to sex is no value. Who would you rather be, the old guy hunched over his cereal who made out with Farrah Fawcett one night at the Jade Room, or the insufferable hipster in the trucker hat who goes home to that hot barista, the one with only two tattoos?

There’s nothing like the first stroll in your new town, which for me and Austin was Sunday, April 1, 1984. I was walking down South Congress (which wasn’t nearly as seedy as developers will have you believe), when I happened upon the grand opening of the costume store Lucy in Disguise with Diamonds. The party spilled out onto the sidewalk, while zydeco music pumped out of the speakers. What a cool town!

Baptised by Buttholes

Next stop was the Continental Club, where the sign said, “Butthole Surfers $3.” I was the first one in the door at 9 p.m., and it was just me and owner Mark Pratz for awhile. Cheryl Newlin, a bartender on her day off, was the second person in. My first friend in Austin!

They didn’t have opening acts in Hawaii clubs, so when Happy Death came onstage at about 10:00 p.m. I thought they were the Butthole Surfers. I was surprised to see another band set up afterwards.

And wonderfully unprepared for the strangeness that would follow. Not many people have seen the Butthole Surfers without knowing a thing about them. This was before all the visual insanity—the penis re-attachment films and the flaming cymbals and the stripper who covered her teeth in aluminum foil. It was just the music, and it was both abrasive and hypnotic. As Gibby yelped and howled his brilliant gibberish, my brain was locked in on the primal stand-up rhythms of Teresa and King, and I’ve been chasing that beat ever since.

“This guy just moved here from Hawaii,” Cheryl introduced me around after the show.

“Why the hell would you leave Hawaii to come here, man?” growled Xalapeno Charlie Duggan, who owned a legendarily spicy Mexican restaurant on Barton Springs Road.

“I’m into bands, not beaches,” I answered.

“Well, then, welcome to Austin,” he said with a handshake.

This history starts with yodeling tavern owner Kenneth Threadgill, the granddaddy of them all, whose performance and encouragement of Austin music dates to the 1933 repeal of Prohibition. Then we step back even further to the German singing societies, which preceded the Volstead Act by several decades. Beer has always played a big part in the history of Austin music.

We end with the launch of South by Southwest, whose registration line would become Ellis Island of the New Austin. SXSW was born in March 1987, the month Kenneth Threadgill died at age seventy-seven of a pulmonary embolism.

You’d think the end of one era in Austin and the beginning of another couldn’t be more succinctly defined, but six years earlier— April 1, 1981—Austin’s first punk club, Raul’s, closed for good on the night hip hop made its live concert debut here. As Sugarhill Gang, Grandmaster Flash, and other acts drew 3,000 to Municipal Auditorium on a Wednesday, rap perched to replace punk as the sound of rebellion in Austin and around the world.

Austin music is not defined by genres, however. Sammy Allred of the Geezinslaw Brothers, the second Austin act (after folk singer Carolyn Hester) to sign with a major label in 1963, used to say, “Austin music is not a sound. It’s a scene.”

Yellow lights on South Lamar . . . capital punishment . . . “Don’t Move Here” t-shirts. What are things that don’t deter?

Austin’s a mulligan town, a do-over land of opportunity for those with low expectations. Some moved here for jobs. They’re called Round Rock residents. But most of us came because we loved the party, you know, the vibe. It started as a room full of conversations on Goodwill couches and someone pulled out a guitar and everyone sang “Blister in the Sun.” We needed only songs and Tamale House #3 to survive.

In the 1970s, Austin had the cheapest cost of living of the one hundred largest cities in the United States. Today, it’s one of the highest. The average one bedroom in Austin costs more to rent than did the Armadillo World Headquarters!

The only Austin we get is the one we got, so let’s make the best of it. Let’s ditch the once-accurate “Live Music Capital of the World” like an itchy scarf. A better city slogan: “Austin: It’s the People!”

Clubs come and go, but what’s always made this community special are the folks who understand how lucky they are to be in the middle of all that soulful music. They were schooled in the essentials by the deejays—Lavada Durst, Joe Gracey, Tony Von, Larry Monroe, Dan Del Santo, Paul Ray, Jody Denberg, and more—and graduated to the clubs, where they worked hard and partied harder to keep this thing of ours going. This book is dedicated to the musicians, the club owners, the bartenders, the fans, the sound techs, the journalists, the scenesters, the faces we used to see out in the clubs who passed away too soon. It could’ve been us, but they took the hit. Death is especially cruel when you’ve got somewhere to go.

I don’t know which quote I love best. “Some moved here for jobs. They’re called Round Rock residents.” - hilarious and true! Or “They were schooled in the essentials by the deejays—Lavada Durst, Joe Gracey, Tony Von, Larry Monroe, Dan Del Santo, Paul Ray, Jody Denberg, and more…” - they were the best and we should all be thankful for them.

Well written opening sir, quite insightful I think and it has a touch of the smartassness that makes you you. The pictures are awesome, I remember some of the places well though I don't think I ever glimpsed the old Soap Creek in the Hills in the daylight. Dodging the craters in the road up there was quite the sport in the dark.