Austin's most historically significant recording

How Mike Levy led to my meeting with R.H. Harris of the Soul Stirrers, which started my second career as a "rock n' roll detective"

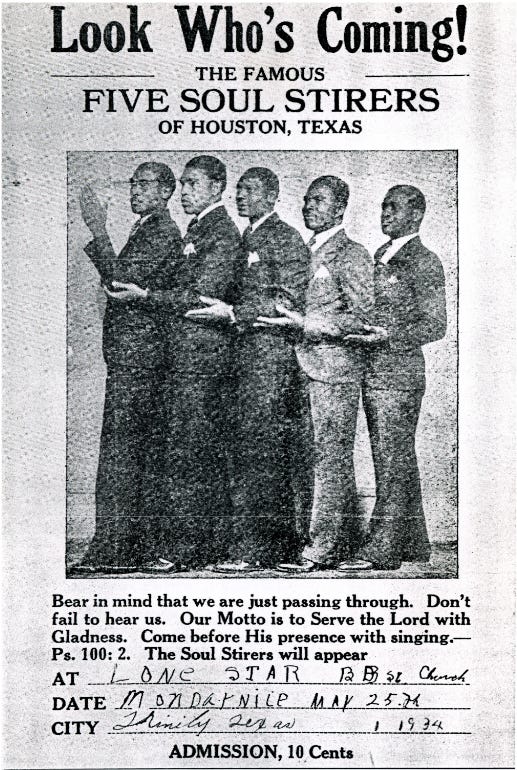

The Soul Stirrers are best known today as the Chicago gospel group that launched the career of Sam Cooke in 1951, but the group is actually from Trinity, Texas, by way of Houston. The Stirrers revolutionized gospel quartets by adding a fifth member- a second lead singer- which upped the intensity when the two leads traded verses while keeping the four-part harmony intact. Before the Soul Stirrers, gospel quartets were mainly barbershop or jubilee groups doing old spirituals like “Down By the Riverside.” But the Stirrers came out to “wreck a house” with their hard gospel style and, in the process, influenced every quartet to follow.

Only Lubbock’s Buddy Holly and the Crickets, the model for the Beatles, T-Bone Walker of Oak Cliff, who invented the language of electric blues guitar, and free jazz pioneer Ornette Coleman from Fort Worth are more influential Texas acts than the Soul Stirrers.

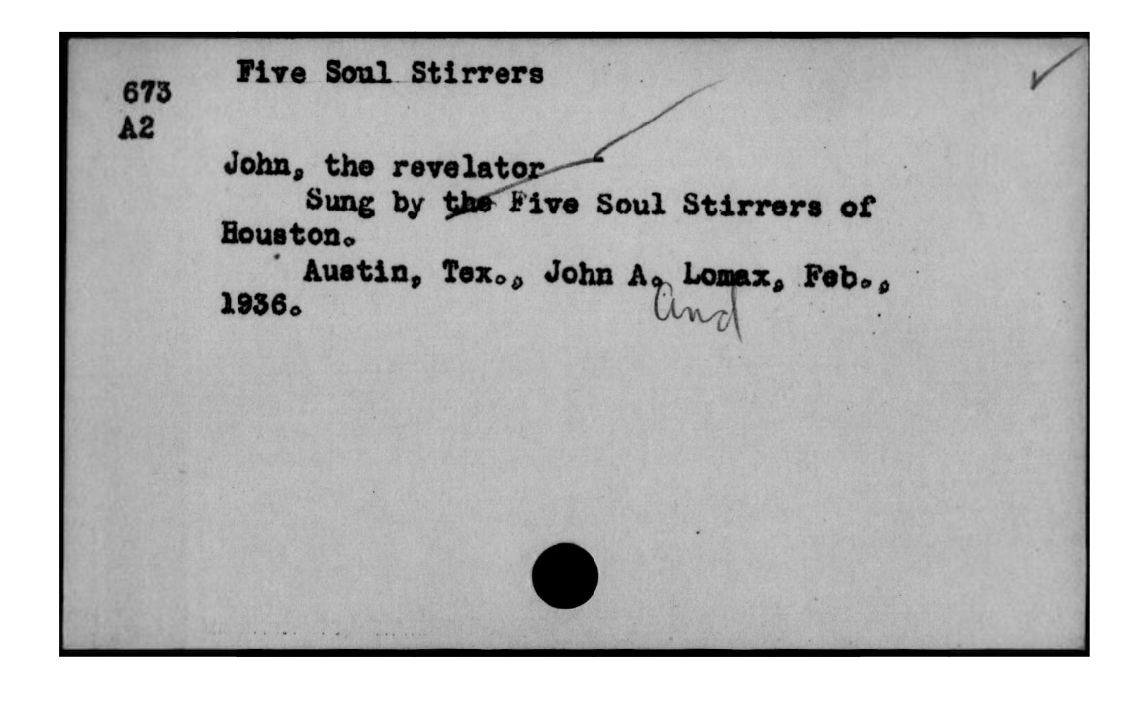

Gospel historians sometimes credit the Golden Gate Quartet as the precursors to the heightened emotionalism of quartets, but the Soul Stirrers actually recorded a year before those Norfolk heavyweights. They made their recording debut in Austin, with John Lomax and his son Alan running the sessions for the Library of Congress. Billed The Five Soul Stirrers of Houston, the group recorded four songs on Feb. 12, 1936: “Lordy Lordy,” “John the Revelator,” “Standing At the Bedside of a Neighbor” and “How Did You Feel When You Came Out of the Wilderness.” These were all songs previously recorded by others, but no one did them with the thrust of the Stirrers, whose performance Alan Lomax called “the most incredible polyrhythmic music you’ve ever heard.”

Those Library of Congress recordings have been preserved in D.C., but never commercially released. But as a representation of what the five singers- E.R. Rundless, W.L. LeBeau, A.L. Johnson, S.R. Crain and O.W. Thomas- were doing onstage at the time, the recordings track a transformative moment in the evolution of spiritual sound. “No other recordings from that era are anywhere close in style,” wrote gospel historian Ray Funk, who pinpoints a Stirrers innovation as the harmony based around a higher tonal center- with “piercing falsetto” and a lighter bass- than the popular quartets from Birmingham Alabama.

It’s unknown where the Soul Stirrers sang for the Lomax recording machine, but John Wheat of the Briscoe Center for American History says the likely location was the big house at 400 E. 34th Street where John Lomax lived with second wife Ruby Terrill and kept his recording equipment. That’s also the residence, torn down in the early ‘70s, where Lead Belly stayed for a spell after his release from Louisiana’s Angola State Penitentiary in 1934.

A name missing from the 1936 Stirrer credits is Cooke’s mentor R.H. Harris, who everyone called “Pop,” not only because his premature balding made him look older, but because many consider him the father of gospel quartet singing. Harris replaced group leader LeBeau, who became a minister, the next year.

In a 1986 interview on a cassette kept at the Texas History Museum on E. 11th St., Harris takes credit for introducing the falsetto to gospel quartets, but Rundless was already using that high-pitched technique when the Lomaxes got it down. The 5 Stirrers were also were doing dual lead vocals in 1936, an innovation credited to Harris. There’s no question Pop Harris took the gospel quartet to new soulful heights, but he was less an originator than a master.

“He perfected a beautiful melismatic style full of breathless, sweeping glissandos, never matched by anyone, before or since,” gospel historian Opal Louis Nations wrote of Harris in 2003.

Here’s a photo I took of Rebert Harris and wife Mary in Chicago in July 2000, followed by the story about how I came to meet my favorite male gospel singer two months before he passed away at age 84.

Before I devoted myself to history, I was prone to hysteria, as a rock critic in love with the notion that opinion can’t be proven incorrect. There was no right or wrong, only interesting or boring. I could be outlandish or just like everybody else. I was tagged a contrarian, with which I totally disagree. I considered myself more like a roast comedian with a backstage pass.

When I was a young writer, I didn’t really know anything so I relied on a fearless attitude to get folks to read my stories. But with age and experience comes knowledge that can entertain in a much more satisfying way. And history has a very definite right or wrong. Making sure your information is accurate requires a work ethic akin to, as Kurt Vonnegut described the writing discipline, inflating a blimp with a bicycle pump. Anybody can do it, but most give up. Sometimes obsession is the talent.

The negative things in your life eventually become positive if you give them time and mileage. That’s another thing I had to learn. In April 2000, the Austin American-Statesman announced that it was suspending my popular local celebrity/society column “Austin Inside/Out,” mainly for its mean-spirited tone. My mea culpa column was written by the managing editor with my byline to give me a flogging I felt was way out of line. I would’ve quit but I had a six-year-old and needed the health insurance.

My column’s demise had been building since Michael Dell’s people called the publisher to protest a line on Dec. 31, 1999. I wrote that “the Dell family will be celebrating Y2K six hours later than the rest of us, but it wasn’t some Jewish holiday thing- they’re in Hawaii.” Our Jewish publisher was hopping mad, but I didn’t see what was wrong with the item. I was put on notice, but I couldn’t help myself.

Last straw status goes to two items: 1) my account of a Texas Monthly photo shoot in which the art director, speaking of clothing, said “there are too many whites over here and too many colors over there.” Everybody laughed because she pointed to a section of mostly white people hanging out over here and then black people hanging out over there, and singer Malford Milligan joked “I haven’t been called colored in awhile.” Everybody laughed. It was all in fun, but there were charges of racial insensitivity in my retelling. TM’s Mike Levy had wanted me fired since Emmis bought his magazine and kept him on as publisher, which I compared to buying a house and keeping the previous owner’s Rottweiler. OK, maybe I was a little mean-spirited. But I was totally accurate in the whites/colors thing. Even Andy Langer backed me up.

But the second reason was all my fault. Being overworked during SXSW- eight columns and two features in seven days- was no excuse to the editors. I fucked up by reporting that Matt’s El Rancho was towing cars, when, actually, they had just threatened to do so, and had an attendant patrolling their empty lot. “Matt’s is towing cars,” a friend told me when I got to Maria’s Taco Xpress that Sunday morning, making sure I didn’t park there. But I didn’t check it out. I tried to make it funny by suggesting that the mighty Matt’s, which was closed until late afternoon, was jealous of their little taqueria neighbor, which was attracting thousands a day to the music and tacos. A lawsuit threat was no laughing matter, so I called every tow yard in town to see if they’d snatched any car from Matt’s parking lot that day, and couldn’t find a one. I had to eat my balls.

My editor Melissa Segrest was sympathetic, taking me aside and suggesting that I use the effort previously devoted to three columns a week for one substantial piece. “Take your time and write the story you didn’t have the time to write,” she said. “Travel if you have to.” God bless her!

A few weeks previously, I had discovered that vintage gospel singer Rebert “R.H.” Harris was still alive in Chicago. In the summer of 2000, I redeemed my Statesman shame coupon to fly up there to interview the frail 84-year-old who mentored “The Man Who Invented Soul.”

The interview turned into a visit. Harris had just had a stroke and didn’t talk much, so there wasn’t anything to build a story around. I had history, but no quotes. Harris passed away a few weeks later and when The New York Times obit contained inaccuracies and understatements, I had to do everything I could to correct this injustice. That the death of this gospel legend caused hardly a blip in the music press was all the motivation I needed to drive to Trinity and interview people who knew him. The subsequent Statesman cover story started a whole new chapter for me.

That’s why I opened my book All Over the Map: True Heroes of Texas Music, which The Times of London called “the work of a rock and roll detective,” with the story of R.H. Harris and the Soul Stirrers. They started something in Austin in 1936, and they started something in me.

MORE READING

My liner notes to Sam Cooke: The Complete Keen Years 1957-1960

I just ordered a copy of one of your books this morning. I'm late to the party but really enjoy your storytelling.

Thank you for the note, for all of them: are their any photographs of the 400 E 34th Street house mentioned therein? Thank you again.