Austin's Posterfarians of the '60s and '70s

Clubs close, bands break up, but posters endure as history to admire. And collect.

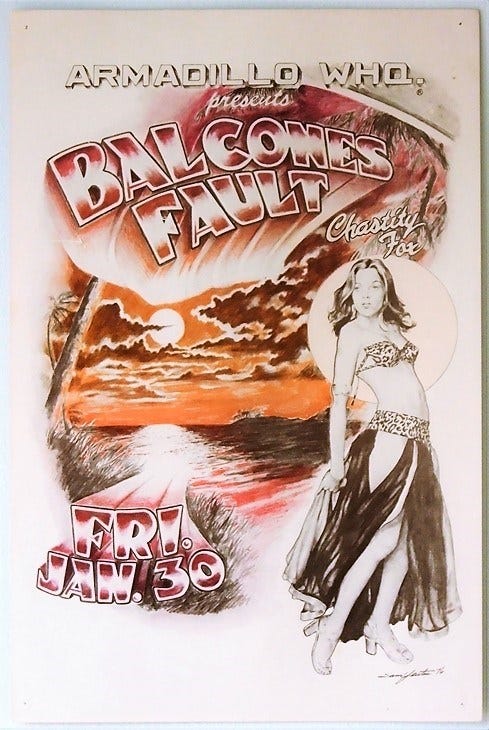

Great music inspires creativity of all kinds, so during Austin’s counterculture heyday- from the opening of the Vulcan Gas Company in 1967 to the closing of the Armadillo World Headquarters on the last day of 1980- a concert wasn’t a reality until it was advertised with a mind-blowing poster. The images and information went together like words and music to create a siren song for fans.

The flat artifacts of anticipation have become, in most cases, the last thing standing. Clubs close and are torn down. Bands break up. But posters endure as history to admire. Original posters from the Vulcan and Armadillo can fetch thousands of dollars- and they used to tape them up in windows and staple them on telephone poles. You want to drive an old Austin hippie crazy, tell him or her how much those posters from their garage sale in 1987 are going for today.

It’s Austalgia at its best. The worst thing about seeing a band in a club is that when the show’s over, it’s over. (Also, sometimes one of the best things.) But a poster is a lasting excuse to daydream back to when you were skinny and your only care was scraping up $67.50 for that month’s rent.

Clubs catering to a range of genres—from the hippie-blues-country mix at the Vulcan, Armadillo, and Soap Creek Saloon, to the blues at Antone’s, and the new wave scene at Raul’s and Club Foot—hired such poster artists as Micael Priest, Danny Garrett, Kerry Awn, Guy Juke, Ken Featherston and Sam Yeates to make their shows seem cooler.

The pioneers of the Austin poster scene were Gilbert Shelton, the original Vulcan art director, and Jim Franklin, who would replace him in ’68, when Shelton moved to San Francisco and launched his underground comic sensation The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers. A spirit of unity among the artists far outweighed any competition, Franklin said. “There was no trace of jealousy or animosity,” he said. “That comes with lesser talents. We just loved art and felt like we were all in it together.”

Though the accepted chronology has Austin artists following San Francisco’s lead, the first ’60s underground comic was actually produced in Austin by artist and historian Jack “Jaxon” Jackson in 1964. Jackson’s 42-page God Nose, xeroxed in the State Capitol print shop after hours, came out four years before the first Zap Comix hit the streets of San Francisco. Jackson and fellow Austinites Shelton, Dave Moriaty and Fred Todd started Rip Off Press, home of the Freak Brothers and Fat Freddy’s Cat, in S.F. in Jan. 1969.

Images of armadillos set Austin apart from the Haight-Ashbury scene of national obsession. Cartooning for UT’s Texas Ranger magazine in the mid’60s, Glenn Whitehead was the first in town to obsess on the armadillo, but Franklin turned it into the mascot for Austin’s hippie-slacker weirdness. In 1968, he was hired to draw a poster for a “love-in” concert at Wooldridge Park and was thumbing through a zoological guidebook when he came across an armadillo. That was the critter, that rat with aluminum siding, that years before had nearly scared the life out of a 10-year-old Franklin when one ran between his legs on a hunting trip with his dad. Franklin drew a ’dillo smoking a joint, giving Austin’s poster scene it’s whimsical, surreal identity. The armadillo slept during the day, coming out at night, and it always had its nose in the grass.

Spencer Perskin of Shiva’s Head Band loved the poster so much he named his label Armadillo Records and hired Franklin to draw the logo, as well as the cover of Shiva’s debut LP on Capitol. Was there any question what the new hippie music hall on Barton Springs Road would be called in 1970?

The image was what mattered for Franklin and the others, with the details of time and place included at the poster’s bottom or edge. “The music was the castle, separated by a moat,” Franklin said. “Then came the village, the marketplace. Every time I drew a poster, it was made so that the information could be cut out and the rest could stand alone as a work of art.”

The star artist of La Porte High School, near Galveston Bay, Franklin attended the Kansas City Art Institute between his junior and senior years. His studies continued at the San Francisco Art Institute before moving to New York City in the early ’60s. That’s where you went to become a famous artist. But it was a chance meeting in Galveston with musician/beatniks Ed Guinn and Travis Rivers that lured Franklin to the capital city in 1965. In September of that year, Austin was the first audience to accept electric Bob Dylan. There was something special about to break in the most liberal city in Texas.

People have made millions of dollars off the art of Franklin, from his posters to his paintings, yet not much came back to him, as he maintains the spartan existence of an artiste. For a time he lived in a former Albertson’s grocery store on William Cannon with like-minded souls. He’s lived at the Vulcan, the Ritz and the Armadillo- home is just a place to sleep when you’re not making art.

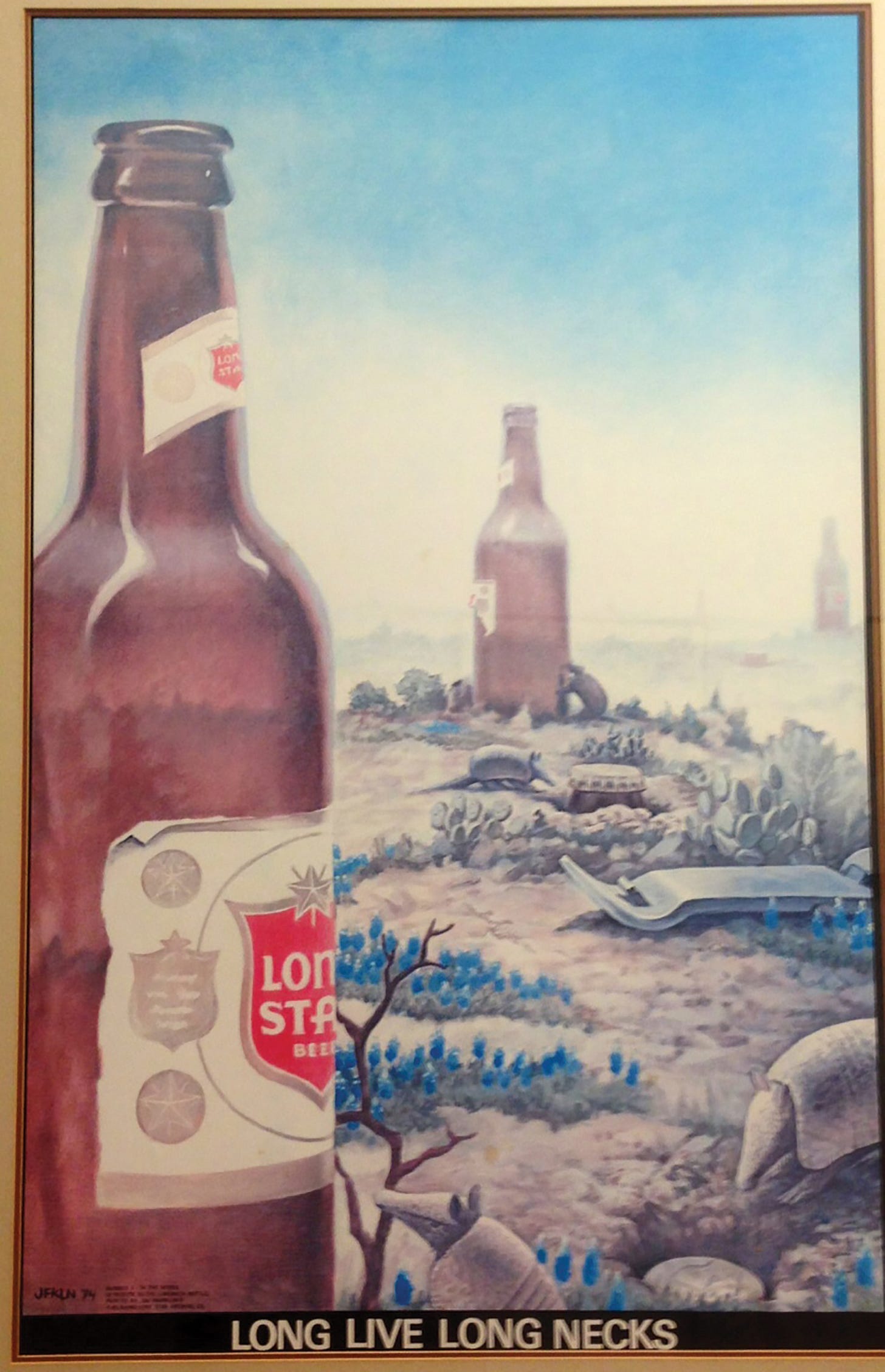

Perhaps Franklin’s most valuable contribution was not visual, but with words. In 1974, he was hired to do a painting promoting Lone Star Beer, and he needed a tag. “Long Live Long Necks” he wrote on the bottom of the painting, a stroke of cultural branding printed on thousands of bumper stickers, and solidifying Lone Star as THE beer of the cosmic cowboy lifestyle. The next year Lone Star sponsored a new live music TV show called Austin City Limits.

Read about the murder of Ken Featherston and other infamous nights in Austin music.

Looking back at VGC posters, it is curious that Jim did not incorporate Armadillos in them, save for the self-portrait in https://technologists.com/VGC/1969/IMG_0281.JPG. My personal favorite of his Armadillo works is 1970 UT student art show (https://technologists.com/photos/1970/fullsize/JFKLNstudentshow.jpg). Hub City Movers played the opening night, my wife Caroline had sculptures and paintings on exhibit, but she and I did not meet until some time later.

Jim Harter deserves at least a passing mention. He did VGC posters and a couple of early AWHQ posters before moving to San Antonio. He is best known for his series of Dover Press clip art books used by thousands of illustrators from myself to the Cheers TV show gang.