Austin became known as a town of free spirits and cheap living in the ’70s and ’80s, but it took a lot of hard work on the ground floor from people like Rod Kennedy to build the Groover’s Paradise that became the Slacker’s Playground. It always started with a love of songs that came from the heart.

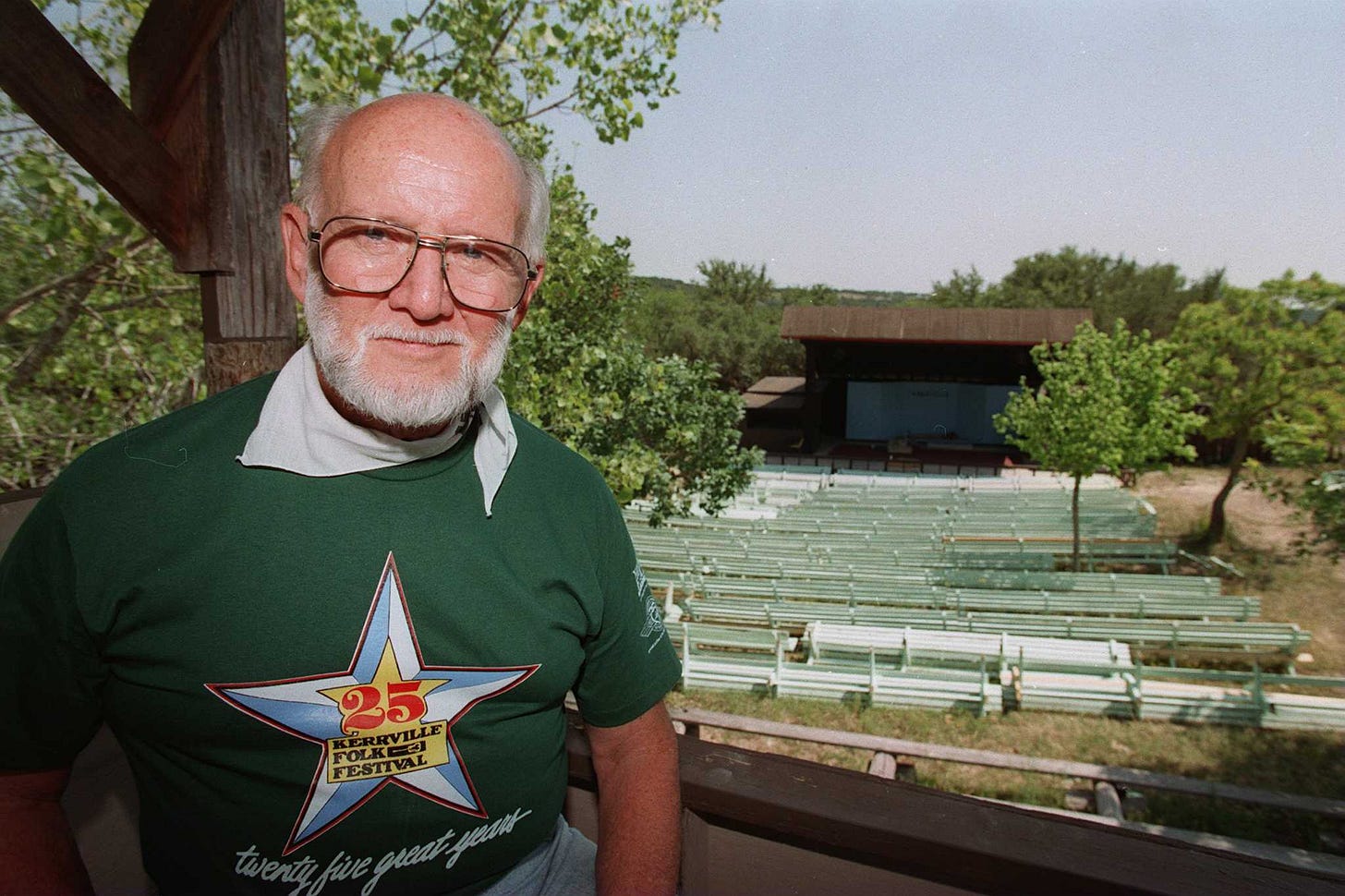

At the 2009 Kerrville Folk Festival at the Quiet Valley Ranch, Kennedy, who founded the event in 1972, was seen standing in front of the empty stage in the middle of the day. “He didn’t know anyone was watching,” said Lloyd Maines, who was sitting under a tree, waiting to teach a songwriting class. “He just stopped and stood there looking toward the stage for a long while.”

In the silence, the veteran promoter no doubt heard music. Kennedy could look back on his five-plus decades in the entertainment business, during which he produced more than 1,500 shows, with great satisfaction. In a town full of talkers, Kennedy, who passed away in 2014 at age 84, was a do-er.

When the Batman TV series with Adam West was a national phenomenon in 1966, leading to a quickie movie, Kennedy flew out to L.A. to convince executive producer William Dozier to have the film’s world premiere in Austin at the Paramount Theater. On July 30, 1966, the entire cast, except Burt “Robin” Ward, whose wife was having a baby, paraded down a Congress Avenue lined with 30,000 fans. Kennedy beefed up the Batman parade with floats announcing the next week’s start of Aquafest, of which he was a director. The event was national news!

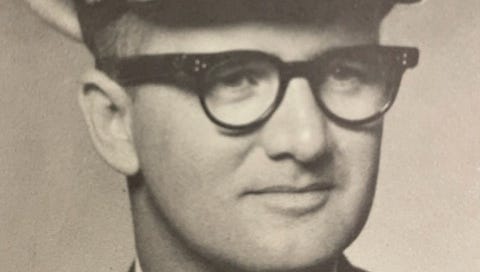

But Austin was in the news two days later, all over the world, when Charles Whitman went on a tower rampage, killing 16 people and ushering in the mass murder-by-gun era in America. That the killer was an ex-Marine especially saddened Kennedy, a proud jarhead who fought in the Korean War.

Austin soared one day, and came crashing down the next, like the up-and-down flow of concert promotion Kennedy learned to accept in a career celebrated with a three-hour tribute concert at the Paramount Theater on his 80th birthday. Such Kerrville favorites as Robert Earl Keen, Ruthie Foster, the Flatlanders, Eliza Gilkyson, Bobby Bridger, Randy Rogers, Terri Hendrix and more performed for “the Rodfather” one more time.

A week before that 2010 show, I visited Kennedy at his condo in Kerrville, where he talked about a profession that began for him as the 16-year-old “boy singer” for the Bill Creighton Orchestra in Buffalo, N.Y. Kennedy didn’t have to haul an instrument, so he was drafted to handle stagehand chores, and within a matter of months was booking the band.

“I was hooked from that point on,” said Kennedy, who loved to sing, especially in barbershop quartets, but found early on that his place was behind the scenes. He moved to Texas in the late 1940s with his mother Dorne when she got a job as a buyer for Palais Royal, an upscale clothier based in Houston.

After his time in the Marines, Kennedy moved to Austin to attend the University of Texas. After graduating in ’57 with a fine arts degree, he stayed and booked jazz, gospel, country, classical, rock, Tejano, Broadway shows, ballets, in addition to the singer-songwriters in Kerrville, where the main stage bears his name.

The first concert under the auspices of “Rod Kennedy Presents” was the 1962 hometown return of Carolyn Hester at Austin Civic Theater Playhouse at 5th and Lavaca. A rising star of the Greenwich Village folk scene, signed to Columbia by John Hammond before he signed her one-time harmonica player Bob Dylan, Hester had not played Austin since 1959 at the Black Angus. The two shows, featuring brother Dean Hester as opening act, sold out, but the guest list was a bitch and Kennedy lost $35. He would get better at saying no.

Under Kennedy’s stewardship, the Kerrville Folk Festival grew from an indoor event that attracted 2,800 people (including a longhaired Lyndon Baines Johnson) over three days into an 18-day event that annually draws more than 30,000 “Kerrverts.” That is, when it doesn’t rain. Downpours limited seven of the first 19 outdoor festivals, leading to the “Kerrville Flood Fest” nickname.

Kennedy was well-established as an Austin promoter in 1972 when organizers of the Kerrville-based Texas State Arts & Crafts Fair asked him to put on a music festival at night to keep the crowds in town. After attendance at Kerrville Municipal Auditorium doubled to 5,600 after the first year, the folk festival moved outdoors in 1974, after Kennedy bought 63 acres nine miles from Kerrville for about $47,000.

Kennedy’s career impacted not only live music, but radio, in Central Texas. As a 24-year-old freshman at UT in 1954, Kennedy used a school project to spearhead efforts to raise money for a campus radio station that would become a reality four years later when KUT-FM went on the air. Weeks after graduating, Kennedy and his new bride Nancylee (the great-grandaughter of former UT president William Prather) bought the KHFI classical music station he had managed while in college for $21,000. Austin’s first FM station, KHFI switched to an adult contemporary format in 1965 and donated all its classical records to KMFA-FM, which went on the air in 1967. When KHFI went into the TV market with UHF channel 42, Kennedy produced The Younger Set, a half-hour live music program that aired at 6 p.m. Tuesdays for 22 weeks beginning in Oct. ’66 with Tim Lively and the Profits as house band.

The roots of Kerrville were planted at the Zilker Hillside Theater in 1964, when Kennedy began booking and hosting the KHFI-FM Summer Music Festival over six nights in July. Monday was Folk Night and featured another homecoming performance by Carolyn Hester, two months after she was on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post. Also on the bill that first year was John Lomax Jr., Lightnin’ Hopkins and Segel Fry.

Teaming up with Newport jazz and folk festivals founder George Wein, Kennedy co-promoted the Longhorn Jazz Festival at Disch Field in 1966 and inside at Municipal Auditorium the next year when it rained. (Kennedy was “the Drought Killer.”) The jaw-dropping lineups included Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Coleman Hawkins, Dave Brubeck, Stan Getz, Jerry Mulligan and Nina Simone, plus homecoming sets from Teddy Wilson and Kenny Dorham. John Coltrane was booked for the first LJF, but had to cancel due to ongoing gum problems. His last-minute replacement, the Miles Davis Quintet, with Herbie Hancock on piano and Tony Williams on drums, would’ve stole a lesser show.

During the festival, Kennedy got a call from the Downtowner Hotel at 11th and Trinity, where the acts stayed. “Thelonious Monk trashed his hotel room,” said Kennedy, who made the jazz legend pay $400 after he admitted swinging from the chandelier.

The Longhorn Jazz Fests lost about $20,000 a year, but Kennedy was great at lining up sponsors- 25 Austinites pledged $1,000 each to bring to town an event that would showcase the live music potential here.

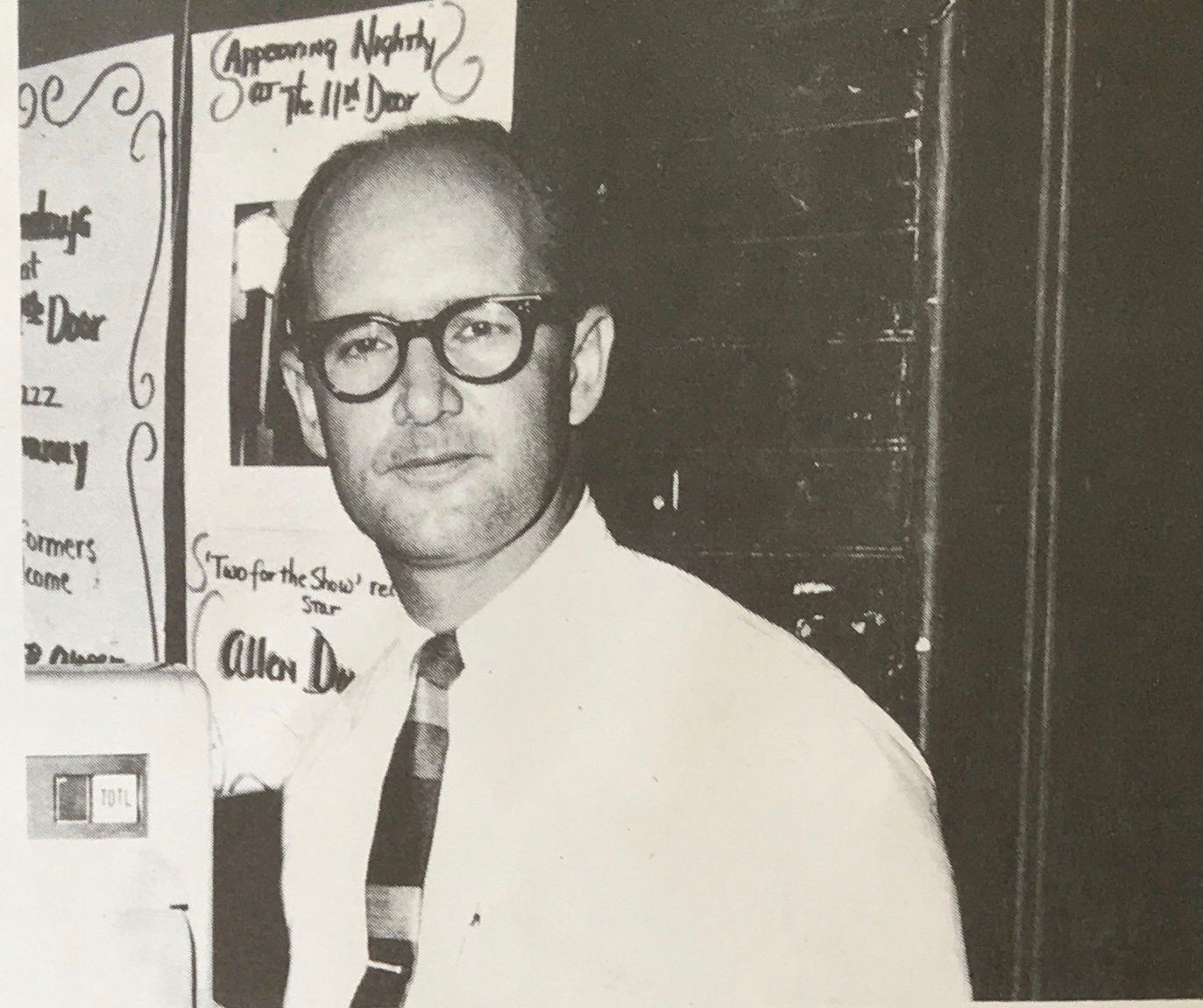

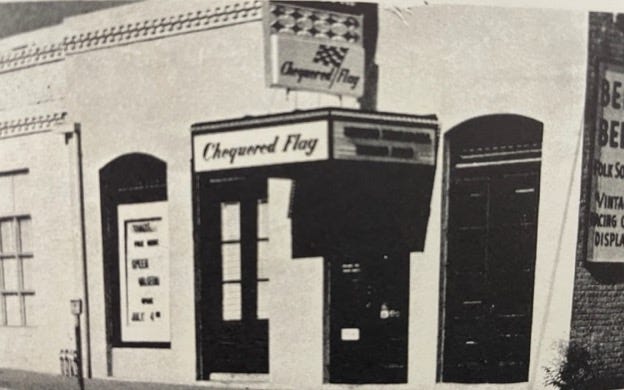

Kennedy’s Chequered Past

Enamored with folk singer Allen Damron, “who reared his head back and sang Pete Seeger songs like they were his own,” he wrote in shelved memoir An Ounce of Difference, which eventually became 1999’s Music from the Heart. Kennedy thought about buying the 11th Door, but decided to build his own folk club at the former Bureau of Water Engineers offices at 1411 Lavaca St.

The Chequered Flag debuted in Sept. 1967 with car racing décor and dipped roast beef sandwiches, reflecting his upbringing in Buffalo. He put the Texas Speed Museum next door to display his collection of vintage Porsches, Ferraris and Maseratis, plus other cars on loan. Kennedy won several races as a driver.

Damron managed the Flag, which was planted in the name of folk authenticity when Woody Guthrie died just two weeks after it opened, and Woody acolyte Segel Fry threw together a brilliant tribute concert. A six-set run by Ramblin’ Jack Elliott in Feb. ’68 solidified the club’s stature. The 11th Door closed that month.

Besides Hester, who packed it five consecutive nights, the Flag featured regular appearances by Jim Schulman, who had a wide repertoire of Israeli folk songs, Jerry Jeff Walker, Three Faces West, Josh White protégé Big Bill Moss, Townes Van Zandt, Frummox, Michael Martin Murphey and a kid from Dallas named Willis Alan Ramsey making his Austin debut. Kennedy also brought in jazz titans Teddy Wilson, Arnett Cobb and Jo Jones.

“A Marine doesn’t fail” was Kennedy’s motto, but the Chequered Flag was becoming an expensive hobby, so it was announced that the club would close in Sept. 1970. Instead, Damron and Fry took over from Kennedy and extended the run to June 1971. One of the last nights featured a screening of Tobe Hooper’s Peter, Paul & Mary doc The Song Is Love, which the Austinite directed right before Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Talk about range.

A conservative owner of sports cars running a folk club in the ’60s may seem incongruous, but Kennedy had always been a model of duality. He could be “a crusty old bird,” as musician Bob Livingston led a memorial piece, but he also helped nurture hundreds of singer-songwriters in his organic setting. His best friend of 40 years was the liberal singer Peter Yarrow of Peter Paul & Mary, yet, until switching parties in 2008 to back Barack Obama for President, Kennedy was an avowed bootstraps Republican.

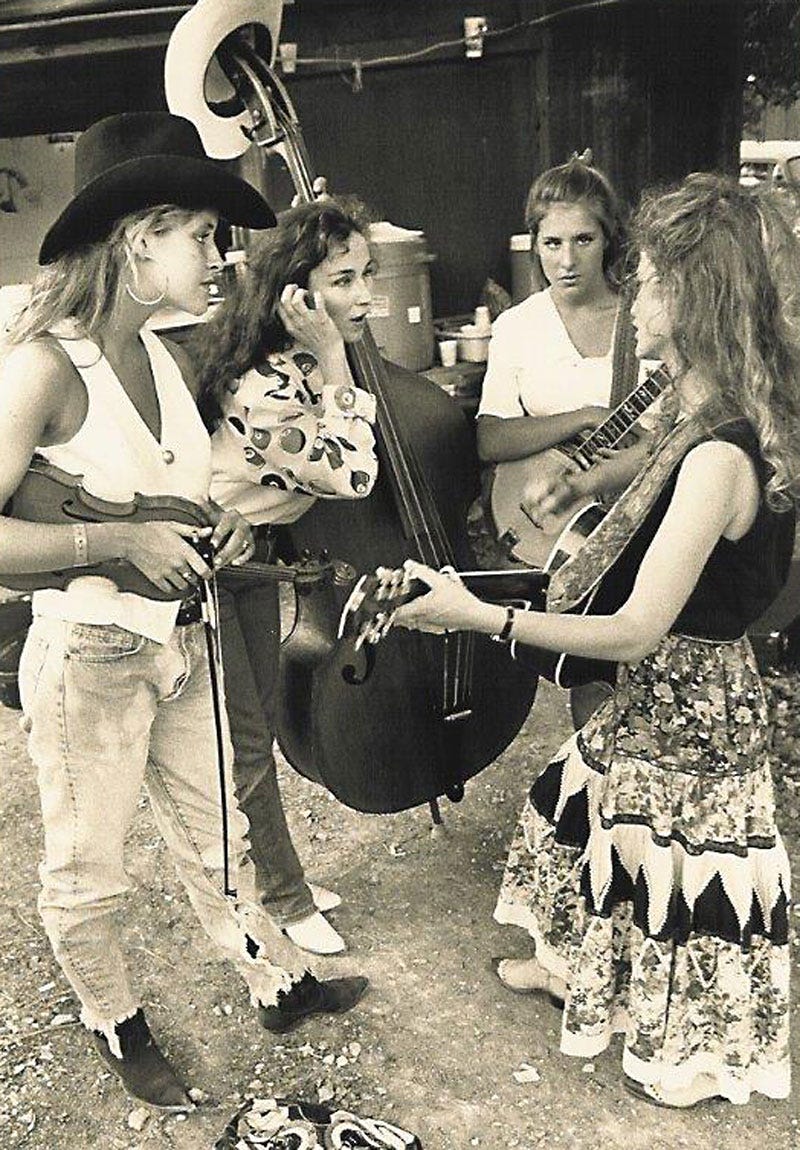

But this right winger also kept his mind open. Because so many young songwriters came to his shows with their guitars, hoping to audition, Yarrow convinced Kennedy to add a New Folk songwriter competition to Kerrville. Winners through the years have included Eric Taylor, Lucinda Williams, Steve Earle, Slaid Cleaves, Hal Ketchum, BettySoo, Tom Russell, Adrianne Lenker of Big Thief, and future political consultant Mark MacKinnon. The New Folk winners concert is always a highlight of Kerrville.

“Rod is that sensitive listener who has the determination to just plow through when things get tough,” said Gary Hartman, former director of Texas State University’s Center for Texas Music History.

Kennedy laid down the rules that kept Kerrville unique: no talking in the audience during a performance, no recorded music between sets, and get that drum circle the fuck out of the campgrounds! There was a “no star” system, where each act got paid the same and the lineup was listed without headliner.

Sometimes the best music was from folks who paid to get in. Unbooked Michelle Shocked got a career without permission when a British label owner recorded her campfire set in 1986 with a Walkman and sold 100,000 records. But the campfires have fallen victim to the burn ban in recent years, replaced by compounds, where campers try to outdo each other with their setups.

I visited Kerrville Folk for the first time in 2022, for the 50th anniversary. I’m not sure Hardline Rod would approve of the psychedelic afterhours blowout it has become. If you’re tripping, it’s a heavenly scene. What’s better than a lusty “Ooh La La” singalong at 5 a.m.? I was thinking sleep, but didn’t have that option.

But Kennedy would’ve loved the heartfelt endurance of “Welcome Home” as the Kerrville salute that sets the festival’s tone. As uptight as the head Kerr-ator could be, he believed in the spirit of music to connect.

Kennedy worked hard and expected the same of those in his employ, even the unpaid. (There’s no better group of volunteers than those who run Kerrville). He also demanded respect for musicians. There was that infamous night at emmajoe’s in the early ‘80s when Kennedy flattened a drunk Blaze Foley, who was causing a ruckus during a folksinger’s set. There had already been bad blood between the two, with Kennedy banning Foley from Kerrville for liberal use of profanity onstage. The 6’4” singer-songwriter crashed the festival in drag the next year.

“I was pretty intimidated by Rod when I met him in 1981,” said Robert Earl Keen. “Not just because of his reputation, but because he ran something that I very much wanted to be a part of.” Keen said that when he was one of five New Folk winners in 1983, “it validated music as a career choice for me.” Many more can say the same.

Kennedy retired from Kerrville in 2002, leaving the producer’s seat to his longtime protégé Dalis Allen, who passed it on to Mary Muse in 2015. He still got a check every month from the Kerrville nonprofit (“My title is consultant, but nobody listens to me anymore.”) and sold Enlyten dietary supplements. Above all, though, he still listened for great songs until the very end. “Music changed my life,” said Kennedy. “When I was in the Marines, I had a mission that had nothing to do with feelings. You’re just not aware of anything else. But I’ve heard songs that made me cry.”

Michael, What a superb article about Rod Kennedy and the Kerrville Folk Festival. Thank you so much

Hope to see you soon at the 51st Kerrville Folk Fest - May 25 - June 10, 2023!!

All the best - Mary Muse

Had the privilege of being introduced to Mr. Kennedy by Chesley Millikin in Ramblin' Jack Elliott's tent at a folk festival in the California Wine Country in the 90's. I graduated from UT in 1987, and knew of Rod, but never imagined meeting him in CA. Told him I wanted "to be like him when I grew up." He gave me his business card, which I still have and never used. Still have not attended the KFF. Should have gone to that 50th in 2022 like you, Michael.. Great story here! P.S. Austin singer-songwriter Kris McKay's dad was the General Manager of KHFI in the 1980's.