“Big Tex” was Daniel Johnston as a guitar evangelist

Bishop McDonald was a surprise cult artist and collage-maker like none other

The Butthole Surfers were the kings of drug-fried musical insanity in Austin in the ‘80s, but an even more off-the-wall act was playing twice a week in East Austin at the time, to fanfare barely contained inside the walls of a dingy church in the basement of a record store.

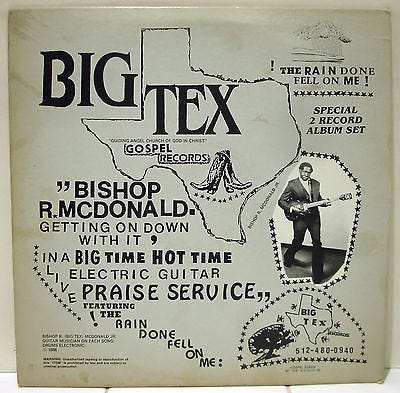

Bishop Ray McDonald Jr. strapped on an electric guitar at the Guiding Angel Church of God In Christ at 1916 E. 10th St. and raged his hardcore gospel blues to the beat of a drum machine, and at the urging of a clump of Pentecostal parishioners. Luckily, some of those frenzied services are preserved on McDonald’s Big Tex label, which put out a couple albums in the 1980s.

All that crazy tongue-people music would be forgotten today if “Rock Daniels,” McDonald’s almost unidentifiable cover of a Sister Rosetta Tharpe song, wasn’t included on the collection Fire In My Bones: Rare + Raw + Otherworldly African-American Gospel, which came out on Tompkins Square in 2011. Curator Mike McGonigal was hipped to McDonald by Friends of Sound Records in South Austin, where he searched for obscure gospel sides whenever he was in Austin from Portland, Ore.

McDonald sold his albums Electrifying Gospel and The Rain Done Fell On Me (a double LP), as well as those of other regional and national gospel acts, at his Big Tex record shop on E. 10th St. A traveling COGIC evangelist based in Houston, McDonald settled in Austin in the early ’80s to help take care of his aging parents and founded the Guiding Angel church. The McDonald family came from Bellville, about an hour west of Houston, then moved to Brenham before the kids grew up and scattered.

McDonald’s primitive music sounds like he’s been dead for years, like it was recorded in the ‘50s, but the good Reverend was still living in Austin’s far eastern “Hogpen” neighborhood (named so because many residents raised livestock on their large lots until fairly recently), when I tracked him down in 2015. He said he was 68, but when he passed a few months later, his given age was 84. But even frail and near-blind, Ray Jr. still had the musical set-up in his collage-wrapped living room: a cheap Roland synth for drums, an electric Epiphone guitar and a little Fender amp. “I mess around with my music every now and then,” he says. “But I don’t got it like I useta.” He tried to play something, but gave up after 10 seconds and put the guitar down.

McDonald spent a couple years in Huntsville prison from age 18-20 for theft, then turned his life around and traveled all over the country as a “fire-rock” preacher. At night he'd collect magazines that featured African Americans and cut out photos for his collages. “I took a little bit from every place I been, every magazine or newspaper,” he said. McDonald put all his collected words and images together in the pamphlet The USA Montage Treasure of Black Song Legends Plus!, which, like all McDonald’s works is right with intention and passion, but short on a professional polish.

One of McDonald’s 12 x 15-inch collages is titled “Austin Texas History” and it covers such local notables as longtime Ebenezer Baptist Church music director Virgie DeWitty, World War II hero Doris Miller, pioneer gospel announcer Elmer Akins, the Bells of Joy hitmakers and Austin’s 1940s mother and sons gospel act, the Famous Humphries Singers. The upper right hand corner commemorates COGIC pioneer Luvenia Taylor, who established 18 missions in Central Texas before she passed away in 1929. Google is entirely unaware of Ms. Taylor or her assistant Sister Brown, but if there’s anything Rev. McDonald knows, it’s COGIC history. One of his finest works of cut-and-glue-and-type is a 27 x 40 inch sheet filled with cut-out heads of Church of God In Christ leaders.

His father was a laborer, a house-party blues guitarist, who wasn’t religious, McDonald said. But his mother Elizabeth (maiden name: Bynum) was a true believer and took her nine children to church with her.

McDonald said he tried concentrating on music as a career when he moved to Dallas in the ’70s, but “everybody kept telling me ‘that’s rock n’ roll. That’s not gospel.’ But I make it about the Lord.”

Usually starting off with a sermon, in McDonald’s calm, descriptive style, he kicks into drive when he starts flailing on his electric guitar and screaming barely intelligible lyrics, while the congregation sings them back to him tenfold. It’s all so raw, going back to the birth of “Holy Ghost baptism” at the Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles in 1906.

McGonigal said “Rock Daniels,” which begins with a Bible recitation from McDonald’s then-wife Lucinda (who did taxes for hire at the record shop), was a favorite of many listeners of Fire In My Bones. “I love how his guitar playing was just the same riff over and over again, but you still want to listen to it multiple times in a row,” said McGonigal. “I love how you can see the process in his work- in the pasteups for his cover art, and in the tape splices on his recordings.” McDonald is the pure outsider artist, the visionary with limited means and education. He didn’t know he was on a CD until the hipster kid across the street told him about Fire In My Bones.

He was a humble man, a lone wolf, a living link to the Pentecostal pioneers who found the best way to praise the Lord through music is to lose themselves in the spirit. He couldn’t do it like he useta, but Ray McDonald Jr. died knowing newer generations were discovering his “electrifying, but not shocking” Wednesday night and Sunday morning wailing sessions from 30 years earlier.

Rev. McDonald’s “Rock Daniels” leads off this great gospel radio show.

Perfect read for a Sunday morning. Thank you, Michael.