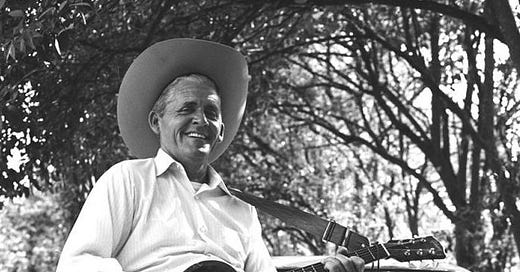

The real Bill Neely

Son of a sharecropper brought authentic Texas music to an Austin scene that craved it

Janis Joplin was who the people came to see at the July 1970 KT Jubilee at a party barn in Oak Hill, but others who celebrated Kenneth Threadgill from the stage included Shiva’s Head Band (whose manager Eddie Wilson was an organizer), plus nascent bluesman Mance Lipscomb, folklorist Stan Alexander, and Bill Neely, a white former sharecropper who put some blues in his country.

Threadgill had a special kinship with Neely, seven years his junior, whose life also changed after an encounter with Jimmie Rodgers as a teenager. Neely was a 13-year-old farm kid from North Texas who saw Rodgers play in a tent in 1929, then shadowed him afterwards. “Why are you following me, kid?” Rodgers asked. “I want to learn how to play guitar,” said Neely. So Rodgers showed him a C-chord, and gave him his thumbpick. “You’re the only one to ever play this guitar besides me,” said “the father of country music.” You can’t not be a guitar picker after that.

Bill soon after got his first guitar, a red Stella, and practiced endlessly until he was good enough to play the honky tonks. On Saturdays, he and older brother John would hitchhike 30 miles south to Deep Ellum, where the streets were full of blues and country and gospel.

Neely rode the rails for three years during the Depression, occasionally coming back to McKinney, where his family settled. The boxcars were often so filled with better-life-seekers, including families with kids, that the riders had to get off whenever there was a big hill ahead, so the train could make it. “We’d have to walk up the hill, then get back on the train on the other side,” he recalled in a 1973 interview.

In the Army during WWII, Neely got married when he got out and moved to Austin in 1948 to do carpentry work for his wife’s brother, a home builder. The twins, Wanda Kay and Wilma Gay, were born the next year in Oregon. “Daddy was a ramblin’ man,” said Wilma Crocker. “You never knew where you’d wind up.” They ended up in Dallas for almost 10 years, where Neely worked as a street sweeper, then the family returned to Austin in the early ‘60s. Neely worked as a truck driver for the Austin State Hospital, and never missed a Wednesday night open mic at Threadgill’s.

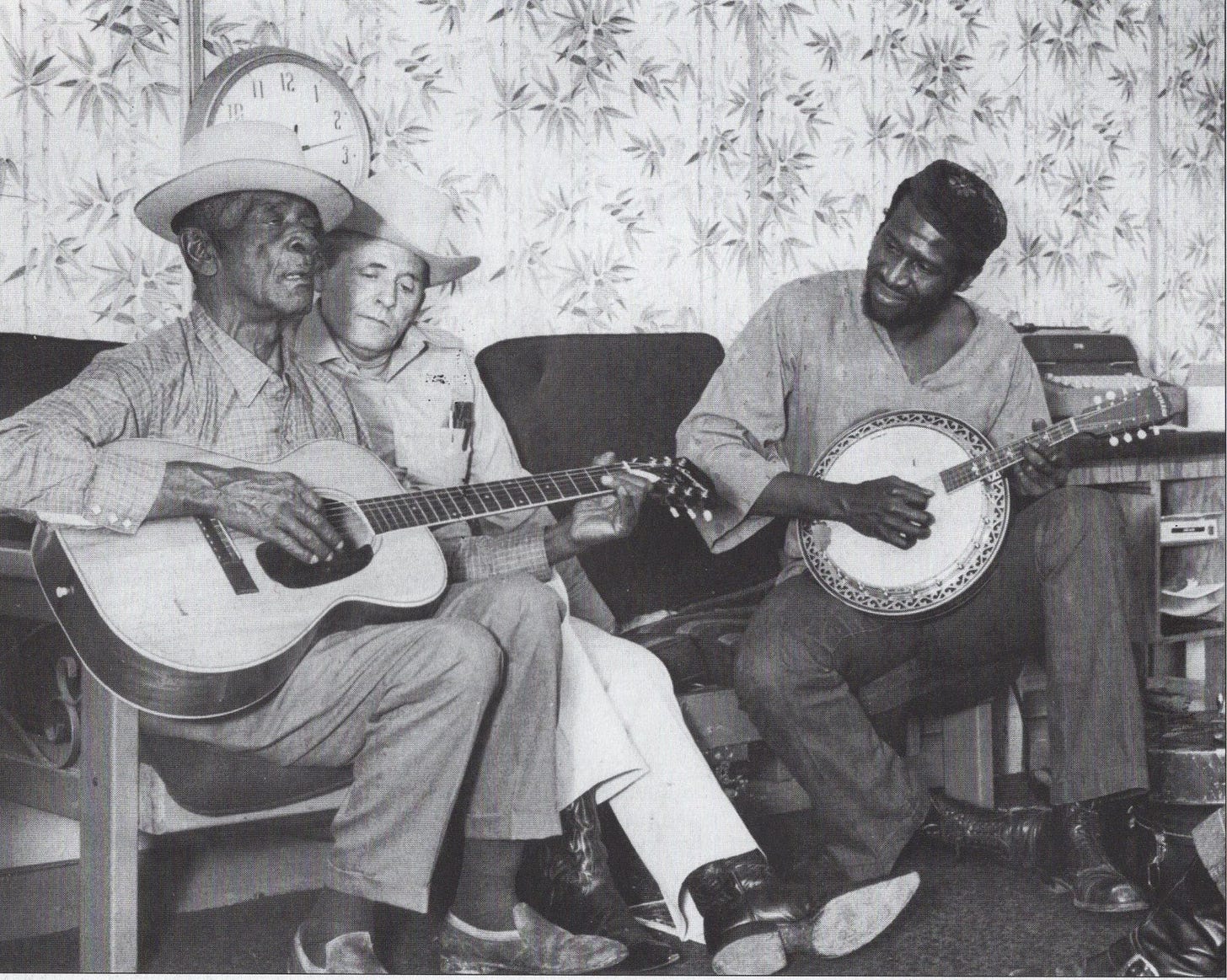

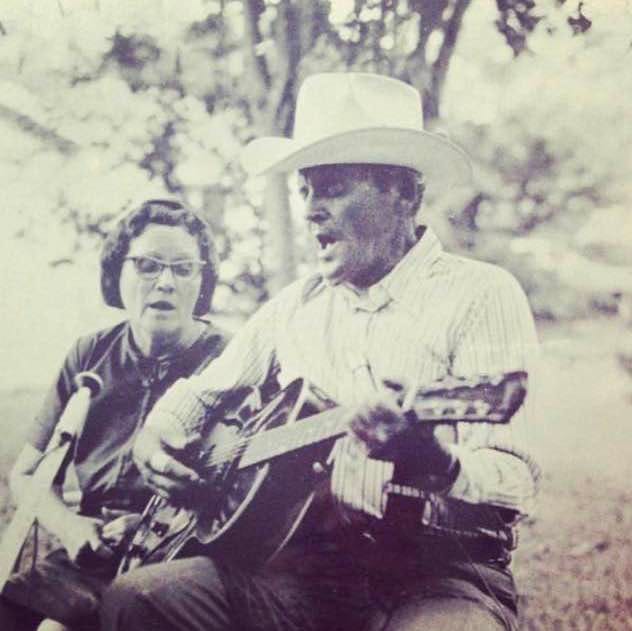

Neely had his first recognition as a musician in 1963 when Johnny Rexx cut his song, “Don’t Waste Your Tears Over Me” for the Starday label. It was just a “jukebox hit” in Texas, but inspired Neely to take his music more seriously. The 47-year-old was fueled by the encouragement he received from Threadgill’s, where he met Mance Lipscomb, a deep bluesman from East Texas who was finding an audience with folk revivalists and blues-loving hippies. Lipscomb and Neely both played bass parts with their thumb, while fingerpicking with the other fingers.

“Mance was already gone when I got to Austin in ‘77,” said J.C. George, who played bass for Neely and Threadgill for about five years, “but Bill talked about him all the time.” Neely visited Lipscomb in Navasota and stayed a few days, the two playing and singing on the front porch for hours.

Like Lipscomb (1895-1976), Neely brought grit to an Austin music scene in the ‘60s full of copy bands aimed at college students. He played the Split Rail before Threadgill and then, with his State Hospital co-worker Larry Kirbo on guitar, Neely did all the folk clubs. He was authentic enough for the roots police at Arhoolie Records, which put out Blackland Farm Boy in ’74. A career highlight was representing Central Texas at the Folklife Festival in D.C. in 1976.

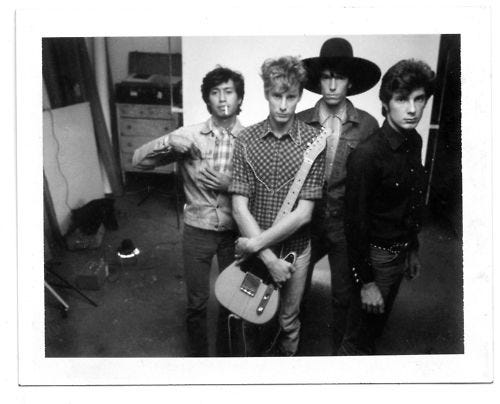

When hotshot L.A. “cowpunk” band Rank and File relocated to Austin in 1981 they were looking for real Texas music and found it in Neely, who opened for them at the Shorthorn Bar on North Lamar.

“He was like a bit of history I could go and talk to,” said Alejandro Escovedo, whose first Austin band was Rank. Both had wives named Bobbi, and Bobbi Escovedo worked at Threadgill’s where Neely played often. “He was always trying to sell me stuff- guitars, Western shirts, cars,” said Alejandro. “My daughter Maya’s first bike was bought from Bill Neely.”

Indeed, Neely often carried a wad of cash in case a bargain showed up. Reselling for profit was another way to make money after he retired. Mandolin player Ben Hogue, who played with Threadgill and Neely before a career building custom guitars and mandos, scored a special piece of jewelry from Neely: a gold ring with a pearl on top that Janis Joplin gave to Neely’s friend Julie Paul, and now belongs to Hogue’s daughter. “I recall paying $120 for it, which was pretty big money for me,” says Hogue, who was making about $300 a week as a trim carpenter at the time.

Neely remained a child of the Depression throughout his life, in music and survival wits. “I was pretty poor,” recalls George, and whenever I’d go over to his house (near 51st and Airport), he’d always make sure there was bacon and biscuits on the stove. He knew what it was like to go hungry.” Neely also knew how to cook- his job in the Army, and several times afterwards.

Neely passed away March 22, 1990 at age 73, just three weeks after he’d been diagnosed with leukemia. He had just come back from two weeks in Paris, performing and mentoring at the House of World Cultures, proudly recognized as one of the original purveyors of American roots music.

But he didn’t have to go overseas to be appreciated, as new generations of young Austin acts sought him out since the ‘70s. He was to High Noon’s guitarist Sean Mencher what Rodgers had been to Neely. “Bill was the perfect marriage of country and blues, the two prominent styles in Austin,” said Mencher. Another fan was Dan Del Santo, the KUT “world beat” DJ who included Neely’s rural country blues with other indigenous styles he played.

One of Neely’s pallbearers- all younger musicians- was J.C. George, who spent a long time at the open casket, because his goodbye included slipping a pick on Neely’s thumb when no one was watching. “I just thought it was the right thing to do,” says George, 71, who carries on the country blues tradition, playing bass with Jake Penrod and His Million Dollar Cowboys.

Bill Neely’s life in music began when Jimmie Rodgers gave him a thumbpick, and “learnt me my first chord,” as Neely put it. He deserved to go out the same way.

LISTEN

35 minutes of Bill Neely interviewed by Chris Stachwitz in 1973.

And here’s a track from Neely’s 1974 LP on Arhoolie, reissued in 2001 as Texas Law and Justice. Lost Art Records released a Neely CD in 2002 titled Austin's Original Singer-Songwriter, culled from a 1985 KUT Live Set with Larry Kirbo and 4 songs from a 1965 recording by Tary Owens with John Moyer on bass.

Wonderful tribute to a humble Texas original who truly can’t be replaced…only commemorated.

I never met Mr. Neely but I did spend a lovely evening with the Texas Songster, Mance Lipscomb, not too long before he passed. Here's a brief account of that evening:

https://1drv.ms/w/s!Ar3l1VHxW5j4l1f38_Ch7FBEIWtm?e=ElrlMO