If you don’t know who to root for in today’s Super Bowl between the L.A. Rams and the Cincinnati Bengals, and you’re a loyal Austin music fan, you might want to go with the Rams. Cincy is the home town of Afghan Whigs, whose leader Greg Dulli was involved in two incidents that helped put two great venues out of business.

The later one is better known. In December ‘98, Dulli got in a fight with a Liberty Lunch stagehand, was knocked out, and hit the back of his head on the concrete floor, which sent him to Brackenridge with a fractured skull. His lawsuit against the Lunch was eventually dropped, but the club got a black eye in the national music press, with bands vowing to never play there. Liberty Lunch was bulldozed eight months later, an eventuality on prime real estate owned by the city, but the Dulli episode may have greenlit the demise. (Even though witnesses said he was the instigator.)

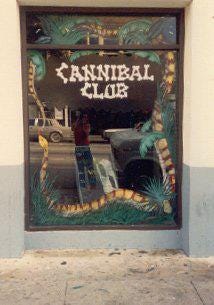

Seven years earlier, a fluke incident involving Dulli was a key piece in the 1991 closing of the Cannibal Club. During a sweaty Whigs show on June 15, 1991, the singer attempted to cool down the crowd with water from a plastic pitcher, but it slipped from his hand and struck a young woman on the forehead, which required stitches. “It was an accident and he was very sorry,” Cannibal Club owner Brad First said. The woman sued the club and won a judgement. “I didn’t have any insurance or any money, so the constable or sheriffs could come by at any time and clean out the cash registers,” First said. Unprepared for the first such visit, the Cannibal lost hundreds of dollars in bar sales, which could’ve gone towards back taxes due to the TABC. After that, First started hiding the money at regular intervals, but the constable kept showing up and taking what he could.

That was pretty much the end of the Cannibal, which closed a few months later. But in two years the club put on a lot of great indie rock shows, and some legendary, thematic hoot nights organized by Mike Hall. “Jesus Christ Superhoot,” “Exile on Sixth Street” and “Roky Erickson vs. Daniel Johnston” drew as well as touring shows by the likes of Ween, Nine Inch Nails, Flaming Lips and Social Distortion.

Red River lost something when First closed the Cave Club in early 1988, and he looked for his next venue, one with air-conditioning this time. He worked at SXSW that March, handling venues downtown, and one of them was Club Coyote, a struggling offshoot of Wylie’s (get it?) at 306 E. Sixth Street. Owner Jerry Creagh saw First, whose track record included Club Foot, as the right person to take over the room, while he retained the master lease. Upstairs was The Loft, a cool “after hours” hangout with occasional bands.

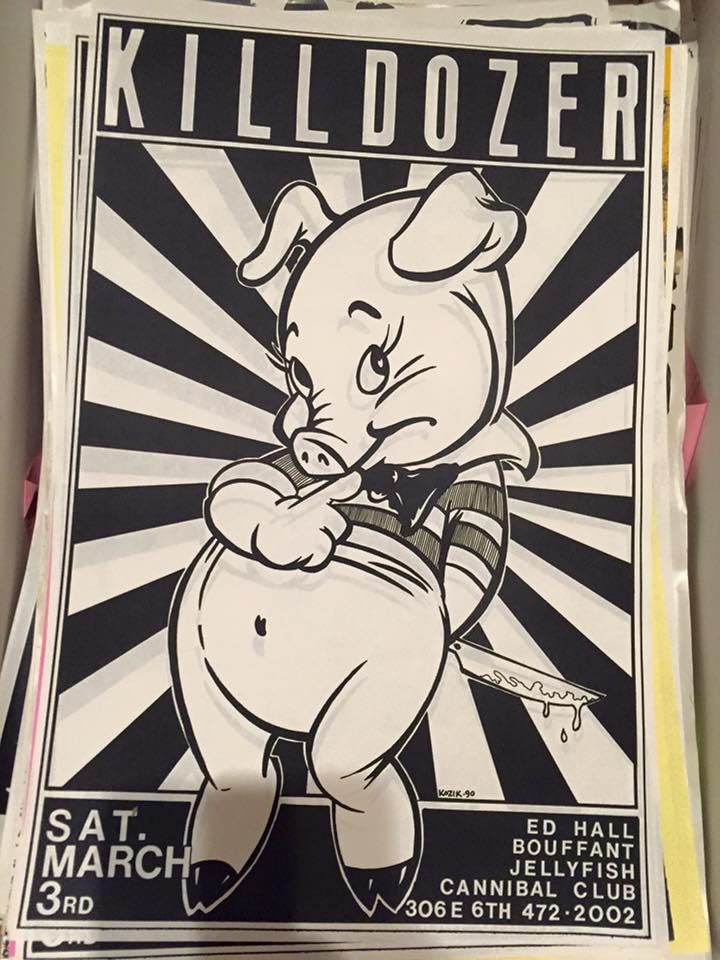

First named his new venue Club Cairo, and when The Loft closed the next month, he took over the upstairs and put in pool tables and a separate bar. The old Cave Club gang, including poster artist Frank Kozik, had a cool new place to hang out.

The liquor license remained in Creagh’s name, but the TABC came down on that arrangement after a few months and said the club needed a separate license. With an angel investor putting up the required $10,000 bond, First got it in his name and Cairo became the Cannibal in April 1989, opening with Grains of Faith and Last Straw.

The Cannibal let musicians in free to support other bands, plus many worked there, including Wammo as DJ, bartenders Max Crawford and John Nelson (Poi Dog Pondering), Kathy McCarty (Glass Eye) and Kay Klier (Bad Mutha Goose). It felt like the musicians ran the place, which was fine by Brad and bar manager Amanda Bowman, who came over from Wylie’s.

With the four-year-old Black Cat Lounge finding itself through residencies across the street, and former bartender Danny Crooks guiding Steamboat into its glory years, with Vallejo, Pushmonkey, Del Castillo, Mr. Rockit Baby and others, Sixth Street had the best live original music scene in town for the first time ever in 1989.

With his TABC problems, First figured that if he changed the Cannibal Club name it might stave off the collection police- and it did for a few months. The Jelly Club, with bands upstairs, and the Jar Bar, with cocktails in mason jars downstairs, seemed to be working until Emo’s opened in May 1992, with the same sort of bands and no cover charge. “That was the knife in the heart,” said First, who closed the Jelly/Jar the next month.