Clubland Paradise: Black Cat Lounge 1985-2002

Sixth Street clubhouse went from biker bar to high schooler hangout

Austin has had some remarkable clubowners, and still does, but there’s never been one like Paul Sessums, a biker who grew up in Austin, married an artist and raised their children in a raging nightclub in the heart of Sixth Street. When Sessums would stand on the sidewalk and rail about this and that, leaning on a parking meter as his pulpit, all was right in his world as long as the guitars were ringing through the doors of the Black Cat.

Wife Roberta den-mothered the lost, as little Sasha picked up empty beer bottles. Paul Jr. (“Martian”), a former punk rocker in Criminal Crew, designed the t-shirts that everyone wore, including Timbuk3 on The Tonight Show. Sasha ran the club in the late ‘90s, after her parents semi-retired to Palacios, on the Gulf Coast.

The night Sasha was arrested for refusing to turn down the band after repeated noise complaints, Paul Sr. was both proud and livid. The next night there was a big hand-made sign that said “Shhh! People are trying to sleep.” Another one declared Austin “the Dead Music Capital of the World.”

The thing sometimes overlooked about all the legendary Austin music clubs is that their calendars had a lot of filler, with maybe six or seven happening shows a month. Even the Armadillo had its cricket nights. But the all-ages Black Cat was almost never dead, seven nights a week, even if the music that night was not your thing. It was a whole scene, lorded over by a biker in a beret with a devilish smile.

Bands that played the Black Cat had to do 3-4 hour sets, no breaks, and for that they were paid handsomely. Paul gave them all the door, which for top acts like Soulhat, Joe Rockhead, Little Sister, Johnny Law, and Ian Moore, could be as much as $3,000 a night if they turned the house. Which isn’t hard to do when you’re playing for four hours. The only rule was no whining.

Evan Johns and the H-Bombs were the first group to draw music fans to that biker bar at 313 1/2 E. Sixth, the original BC location. The tip jar was on a pulley overhead, and if you’d been there awhile and hadn’t tipped, Sessums would make the jar dance over your head until you threw in some coin. The Black Cat moved to the bigger 309 E. Sixth, and that’s where it really took off. When Sessums was told he needed a permit to sell hot dogs in his club, he gave them away, for years, until the health department shut the free weiners down. They took away dinner to many.

The first real sensation was Two Hoots and a Holler, who packed the place every Monday night from ’89 to about ‘91. They had the songs and the attitude and major frontman talent in Ricky Broussard. One night Broussard decided to take a break after landing wrong on one of his trademark leaps, and Sessums was in his face. “What’s the matter, is your pussy sore?” The pair had to be separated. And that was it. The lucrative “Two Hoots and a Hotdog” residency, for both club and band, was over. But that was Paul. He didn’t seem to care about money. The Black Cat was never a SXSW venue. It never had a phone and didn’t advertise.

Paul Sessums was not a joiner, and when the East Sixth Street Merchants Association would host a street fair, he’d undercut their $4 beer cups by selling ice cold tallboys from a table in front of his club for $1.50 each. It was never considered breaking even when Sessums got a chance to stick it to the man.

Another financially-quirky thing the Black Cat did in the beginning was have the band’s set start the minute the doors opened. Paul could’ve sold more beer by letting the milling crowd in an hour earlier, but he didn’t like people waiting around in his joint. Plus, it made the bands start on time. This rule changed in the ‘90s glory years, when cover charges started and it took longer to get the crowd inside.

The Black Cat nurtured many different scenes in its 17-year-run. It was the home of country, rockabilly, funk, jamband, blues, soul and whatever you’d call Flametrick Subs with Satan’s Cheerleaders. The club was also the first on Sixth to regularly book hip-hop- every Thursday night in 1990- when a short-term transplant from D.C. named Citizen Cope made his stage debut.

When Paul Sessums died in a single car accident near Bastrop in 1998, the Black Cat opened for business as usual at 10 p.m. that night. There were signs in front- one proclaiming that the Black Cat didn’t sell martinis or cigars (this was during the swing fad)- but no memorial of the founder’s passing. But that’s how Paul Sr. would’ve liked it. He never could stand crybabies.

The Black Cat Lounge burned down in 2002 and has never been rebuilt, or relocated.

We would park our motorcycles in front, get a bucket of 6 ice cold long necks and sit on the curb.

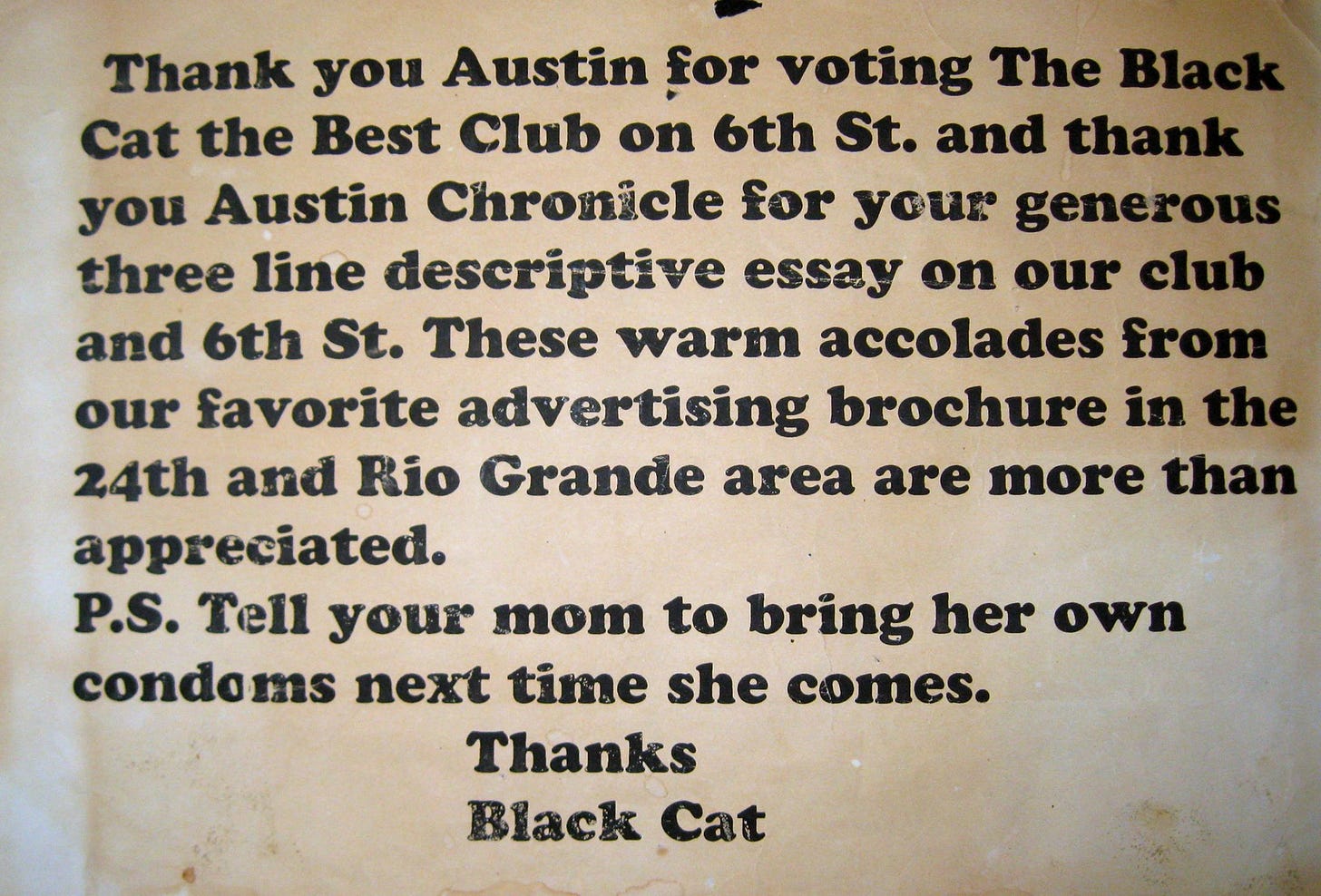

I liked the sign in the window at the first location:

No Cover

No Requests

Almost as much as I liked parking my Beemer next to Paul's Moto Guzzi in that long line of HD stuff the Bandidos rode.