Clubland Paradise: Sixth Street '70s- '90s

Antone's led the way in '75, but Steamboat and Black Cat kept it going

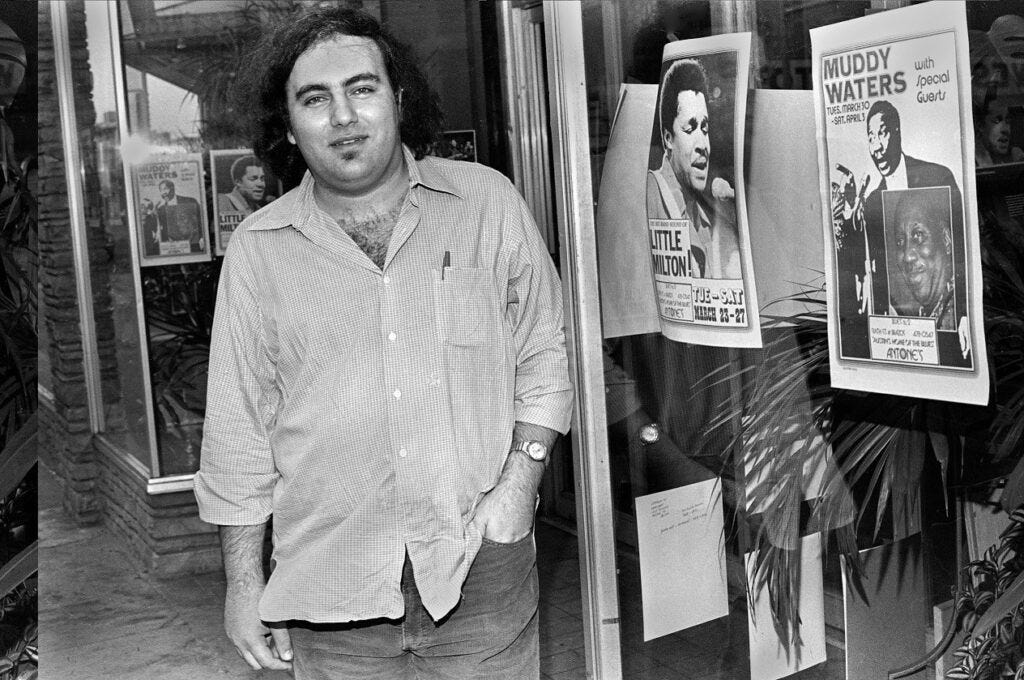

ANTONE’S #1 1975- 1979

There’d already been blues on Sixth, with Brooks’ Home Cooking (418 E. Sixth) much more than a restaurant, and the Lamplite Saloon (currently Blind Pig Pub), where the Fabulous Thunderbirds played their first gigs in 1974 with original singer Lou Ann Barton. Hell, John Lee Hooker played the Ritz in March ’75. But no club elevated the blues scene like Antone’s, which opened at 141 E. Sixth on July 15, 1975. The former Levine’s department store became “Home of the Blues” almost overnight.

Port Arthur native Clifford Antone was a blues fanatic who wanted to meet all the living Chicago legends, so he opened a club that would treat them like royalty. Antone’s hosted the likes of Muddy Waters, Albert King, Albert Collins, Eddie Taylor and Jimmy Reed for five nights in a row, giving them a break from the road. The audiences would be filled with blues-crazed young musicians, who got to hang out with their idols after the show. That’s how Stevie Ray Vaughan met Albert King, and the mutual appreciation began.

But the City Council voted to bulldoze the musical classroom in 1979, along with the rest of the 100-year-old Bremond Building, which included the great Cajun restaurant Moma’s Money, O.K. Records, Ed’s Shine Parlor, and Don Politico’s Tavern. In its place came a parking garage for the Littlefield Building.

Antone’s moved far north, the first of five relocations through the years. Though the club’s longest tenure was at 2915 Guadalupe St. (1982- 1997), some say the original, which also served those Famous Antone’s Po’ Boys from Uncle Jalal’s Houston shops, has never been topped.

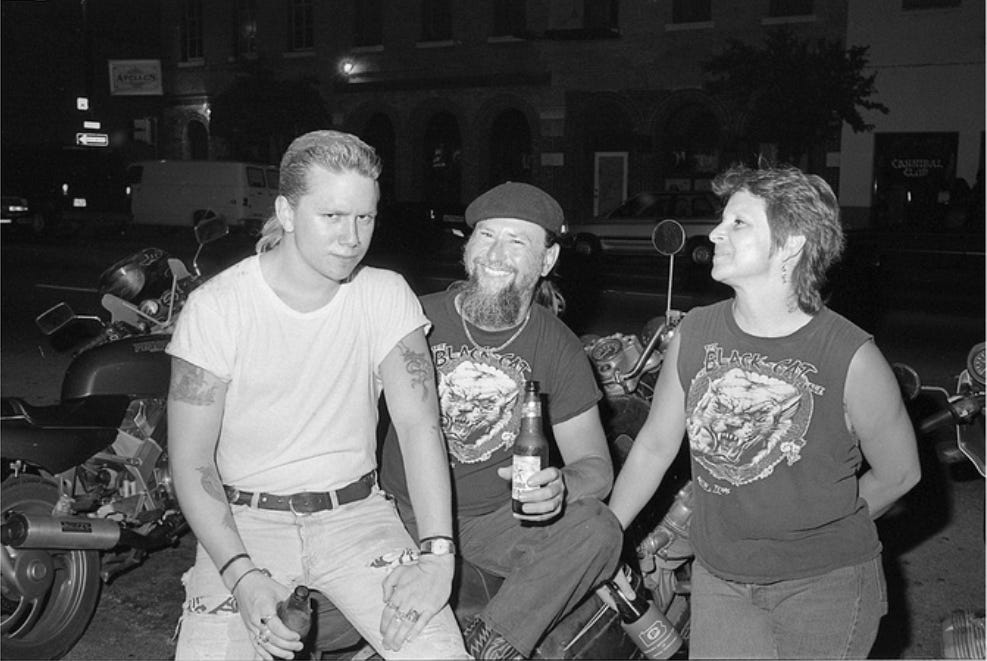

BLACK CAT LOUNGE 1985-2002

Austin has had some remarkable club owners, and still does, but there’s never been one like Paul Sessums, a biker who grew up in Austin, married an artist and raised their children in a raging nightclub in the heart of Sixth Street. When Sessums would stand on the sidewalk and rail about this and that, leaning on a parking meter as his pulpit, all was right in his world as long as the guitars were ringing through the doors of the Black Cat.

Wife Roberta den-mothered the lost, as little Sasha picked up empty beer bottles. Paul Jr. (“Martian”), a former punk rocker in Criminal Crew, designed the t-shirts that everyone wore, including Timbuk3 on The Tonight Show. Sasha ran the club in the late ‘90s, after her parents semi-retired to Palacios, on the Gulf Coast.

The night Sasha was arrested for refusal to turn down the band after repeated noise complaints, Paul Sr. was both proud and livid. The next night there was a big hand-made sign that said “Shhh! People are trying to sleep.” Another one declared Austin “the Dead Music Capital of the World.”

The thing sometimes overlooked about all the mythical Austin music clubs is that their calendars had a lot of filler, with maybe six or seven happening shows a month. Even the Armadillo had its cricket nights. But the all-ages Black Cat was almost never dead, seven nights a week, even if the music that night was not your thing. It was a whole scene, lorded over by a biker in a beret with a devilish smile, who gave bands weird sound advice: “Turn up the bass 23% and turn down the guitar 8%.”

Groups that played the Black Cat had to do 3-4 hour sets, no breaks, and for that they were paid handsomely. Paul gave them all the door, which for top acts like Soulhat (with Frosty the drummer), Joe Rockhead, Chris Duarte, Little Sister, Johnny Law, and Ian Moore, could be as much as $3,000 a night if they turned the house. Which isn’t hard to do when you’re playing for four hours. The only rule was no whining.

Evan Johns and the H-Bombs were the first act to draw music fans to that biker bar at 313 1/2 E. Sixth, the original BC location. The tip jar was on a pulley overhead, and if you’d been there awhile and hadn’t tipped, Sessums would make the jar dance over your head until you were shamed to throw in some coin. The Black Cat moved to the bigger 309 E. Sixth in ‘88, and that’s where it really took off. When Sessums was told he needed a permit to sell hot dogs in his club, he gave them away, for years, until the health department shut the free weiners down. They took away dinner to many.

The first real sensation was Two Hoots and a Holler, who packed the place every Monday night from ’89 to about ‘91. They had the songs and the attitude and major frontman talent in Ricky Broussard. One night Broussard decided to take a break after landing wrong on one of his trademark leaps, and Sessums was in his face. “What’s the matter, is your pussy sore?” The pair had to be separated. And that was it. The lucrative “Two Hoots and a Hotdog” residency, for both club and band, was over. But that was Paul. He didn’t seem to care about money. The Black Cat was never a SXSW venue. It never had a phone and didn’t advertise.

Paul Sessums was not a joiner, and when the East Sixth Street Merchants Association would host a street fair, he’d undercut their $4 beer cups by selling ice cold tallboys from a table in front of his club for $1.50 each. It was never considered breaking even when Sessums got a chance to stick it to the man.

Another financially-quirky thing the Black Cat did in the beginning was have the band’s set start the minute the doors opened. Paul could’ve sold more beer by letting the milling crowd in an hour earlier, but he didn’t like people waiting around in his joint. Plus, it made the bands start on time. This rule changed in the ‘90s glory years, when cover charges started and it took longer to get the crowd inside.

The Black Cat nurtured many different scenes in its 17-year-run. It was the home of country, rockabilly, funk, jamband, blues, soul and whatever you’d call Flametrick Subs with Satan’s Cheerleaders (Sasha’s favorite band.). The club was also the first on Sixth to regularly book hip-hop- every Thursday night in 1990- when a short-term transplant from D.C. named Citizen Cope made his stage debut.

When Paul Sessums died in a single car accident near Bastrop in 1998, the Black Cat opened for business as usual at 10 p.m. that night. There were signs in front- one proclaiming that the Black Cat didn’t sell martinis or cigars (this was during the swing fad)- but no memorial of the founder’s passing. But that’s how Paul Sr. would’ve liked it. He never could stand crybabies.

The Black Cat Lounge burned down in 2002 and has never been rebuilt, or relocated. Or recreated.

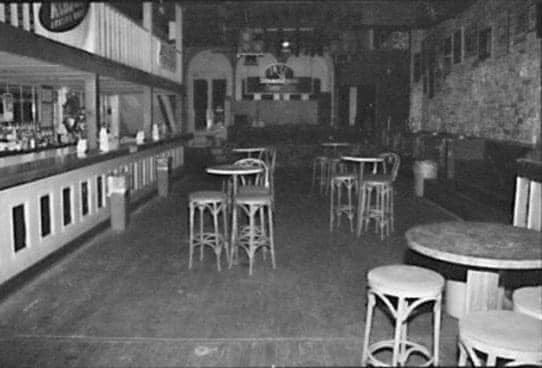

STEAMBOAT 1978-1999

The first real rock club on Sixth Street, Steamboat was originally a restaurant/bar like the original Steamboat Springs on Burnet Road, owned by Sonny Neath and managed by Lorraine Vick.

Steamboat II opened in 1978 at the former location of Billy Shakespeare’s disco, which had backgammon in the basement. Though it was never really the cool club, Steamboat on Sixth was a consistent positive on the scene for 21 years until it was priced off the block in 1999.

Stevie Ray Vaughan recorded In the Beginning there April 1, 1980 (it aired live on KLBJ-FM) and regulars included Eric Johnson, Van Wilks, Extreme Heat and the Bizness. It was a cover band paradise where a pre-Grammy Christopher Cross sang “Sister Golden Hair” just six months before America was opening for him on a national tour.

In the mid- ‘80s, Steamboat owner Craig Hillis and manager Hank Vick started regularly booking national acts like Los Lobos, Red Hot Chili Peppers and Jason and the Scorchers. But the club’s glory years were in the ’90s when bar manager Danny Crooks took over booking and built a scene on local bands like Joe Rockhead/Ugly Americans (with Bob Schneider), Vallejo, Little Sister, Pushmonkey, Ian Moore, Breedlove, Sunflower and many more. It was an old-fashioned rock box, where you went to hear loud music and tried to find someone to sleep with. And you got drunk. If it wasn’t happening at Steamboat, the Black Cat was just a block away.

Crooks eventually bought this clubhouse in 1996, but had only three years before his landlady gave him 60 days to vacate. She leased the building to a nightclub group from San Antonio at a rent 2 1/2 times higher than the $3100 a month Crooks was paying.

On Steamboat's last night, Sept. 26, 1999, reunited headliners Joe Rockhead led amped-up club regulars in trashing the place, spray-painting the walls, smashing mirrors and bathroom fixtures and demolishing the stage and sound booth. "I don't think Danny's going to get his deposit back," KLBJ FM's Bob Fonseca said the next morning.

"The new owners said they were going to gut the place," said Crooks, who was already home when the carnage erupted. "We just helped 'em get started."

Antone’s was the first renowned club on Sixth in 1975, and Steamboat had the longest run, but the Black Cat left the greatest mark, from 1985 through the ‘90s. The Sessums family made Sixth Street weird and wild and outlaw. But the Black Cat was also a place where you could leave your 17-year-old daughter and her friends to see Soulhat (as you parked across the street until they were safely inside.)

Cover photo of Black Cat Exterior by Bill Leissner, who will be a main photo contributor to the book. So happy to share his crucial documentation of the Austin music scene of the ‘80s.

Not relevant to the story, but thanks for publishing that picture of JKC at Steamboat. That’s me in the lighting booth on the mezzanine - no one was obsessed with photographing their lives then, so surprises like this are a real treat.

More great stuff. Sometimes you just stumble into a great place and time and Austin was it for awhile. Keep those stories coming.