Willie and the Coach: Listen or Leave

Longhorn legend Darrell Royal was a big fan of sad songs

As the party roared across the courtyard of the AT&T Hotel at UT in March 2011, the namesake of the Darrell K Royal Songwriters Homecoming sat in an otherwise empty amphitheater with his wife, Edith. The iconic Texas football coach, who would be 87 in four months, was saving his strength for the music. He sat there an hour before showtime, third row center, staring at the stage full of guitars, and smiled. Soon such top flight singer-songwriters as Don Schlitz (“The Gambler”), Mike Reid (“I Can’t Make You Love Me”), Michael Martin Murphey (“Wildfire”) and Larry Gatlin (“All the Gold in California”) would be performing the sort of songs that have long provided a sanctuary for the coach who is also the fan.

“What Coach loves to do more than anything else in the world is to sit around and listen to a bunch of songwriters sing sad songs,” Willie told Third Coast Magazine in 1986. The old Villa Capri was a favorite spot of these “pickin’ parties,” as was Royal’s suite after bowl games, or at the coach’s house. Imagine the thrill for a music fan to have Kris Kristofferson, Rita Coolidge and Charlie Rich singing “Why Me” in his living room one Sunday at dawn after an all-nighter.

“We used to call ‘em ‘red light parties,'” said Gatlin, who met Royal in 1973. “Darrell would have a red light in the room where we’d play and if you were in the audience talking or making any noise, the light would go on.” The message was simple and unyielding: Listen or leave. Even whispering was not tolerated.

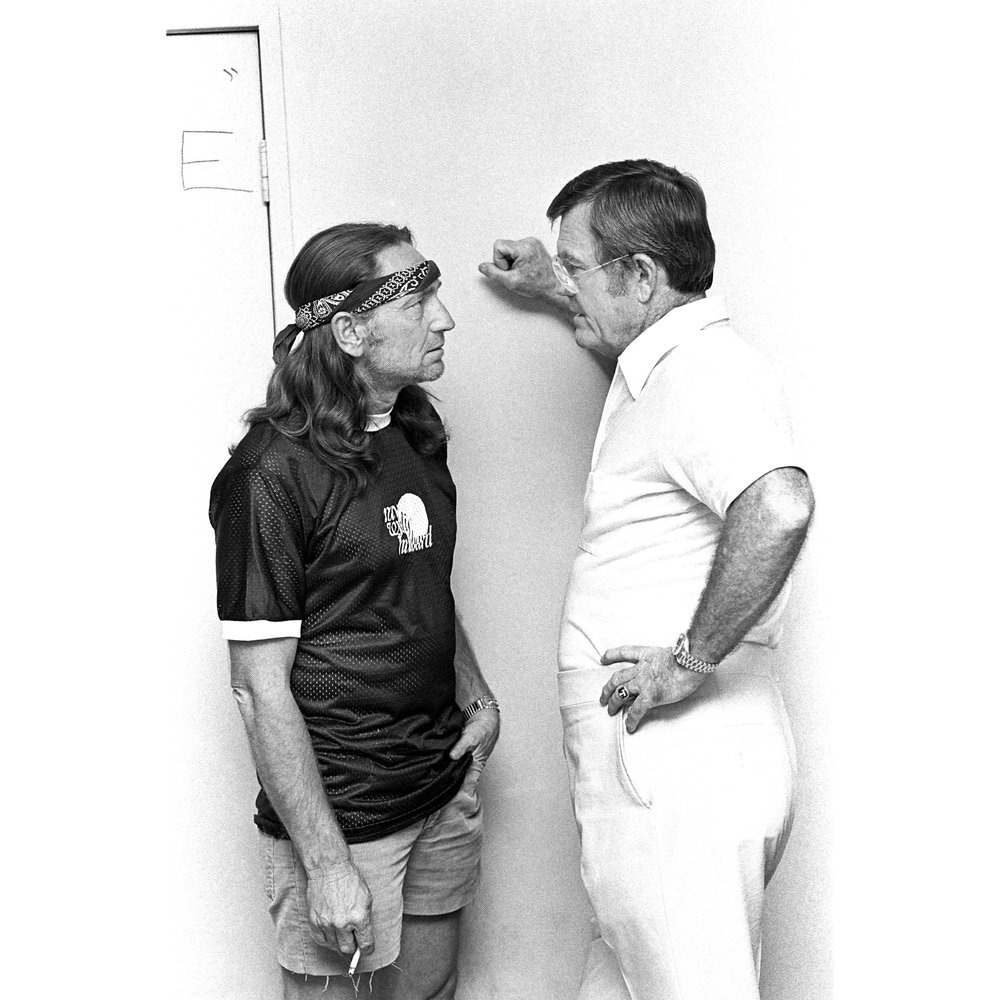

“The words meant something to him,” Spike Dykes, the longtime Texas Tech coach, told ESPN Magazine in 2012. Getting his start on Royal’s staff from ’72-’76, Dykes witnessed, firsthand, the connection with Willie. “You had these two people who you would think, by looking at them, were complete opposites. But they both grew up in the Depression in small towns. So they had similar backgrounds.”

Coach Royal was also a wordsmith, with such notable quotables as, "I was so poor that I had a tumbleweed as a pet." Another: "The real make of a man is how he treats people who can do nothing for him." Royalisms about football especially endure: “Three things can happen when you throw the ball and two of them are bad.” And “dance with the one that brung ya.”

When the Coach passed away in Nov. 2012 at age 88, Willie lost perhaps his greatest supporter. Royal’s embracement of the pot-smoking, pigtail wearing Willie went a long way in making the “outlaw country” icon okay to football fans not usually known for tolerance and acceptance. And the universal appeal just kept spreading.

They went back to the late ’50s, when Royal, hired to coach the Longhorns in 1957 at age 32, never missed a country music package show at the old City Coliseum. Headlined by the likes of Johnny Cash, Buck Owens and George Jones, the shows often found Nelson, a hit songwriter whose jazz phrasing kept him off country radio, way down on the bill.

“I just bought my ticket and sat out in the audience, and no one paid any attention if I was coming or going,” Royal told Third Coast writer Brad Buchholz. “But then we won some football games, and I guess I became more visible.” Soon, the promoters were bringing the young coach and his wife back to meet the performers.

They hit it off instantly with Nelson, who had short hair and wore a suit back then, and often caught his club gigs at Big G’s in Round Rock and the Skyline Club and the Broken Spoke in Austin.

It wasn’t until 1967, however, that Royal became a full-fledged Willie-phile. The Longhorns football team stayed at the Holiday Inn on Town Lake on the nights before home games, and it just so happened that one Friday, Nelson and his band were at the same hotel.

Willie left a message at the front desk, letting Royal know what room he was in, and the coach popped in for a visit before a team meeting. As Royal was leaving, Willie gave him a copy of The Party’s Over, an album he’d just cut. “To Darrell Royal, one of country music’s best friends,” Willie signed it.

“So I took the album home and listened to it alone, where I could really listen to it,” Royal told Buchholz. “I became a real Willie fan right then, as soon as I took the time to really listen.” Royal played the album for everyone he could. This Willie Nelson guy, he’d say, is really something special. This was five years before Willie played the Armadillo.

Royal invited Nelson to play concerts for the team before three consecutive Cotton Bowl appearances, which included the win against Notre Dame which cemented the 1969 national championship.

At a guitar pull following the Longhorns’ 1973 Cotton Bowl victory over Alabama, Royal introduced Nelson to a young harmonica player he’d seen play with B.W. Stevenson. And Mickey Raphael has been with Willie ever since. “How much are we paying that kid?” Willie asked drummer Paul English, who handled band finances, when Raphael first started sitting in. We’re not paying him anything, replied English, to which Willie said, “then double his salary!”

Royal’s love of country music goes back to his boyhood in Hollis, Okla., where he would escape the Great Depression by spending hours in the garage listening to Jimmie Rodgers, the Chuckwagon Gang and Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys on his brother’s radio.

“The big appeal of country music,” Royal told the Alcalde student magazine in 1969, “is the simplicity and honesty of it. All the songs are about some ol’ boy who’s down on his luck or made a mistake he’s gonna have to pay for. Things that have happened to all of us at one time or another.”

In the late ’40s, when he played quarterback and defensive back for the Oklahoma Sooners under Bud Wilkinson, football became his focus. But Royal would always kick back with some ol’ Hank Williams or Ernest Tubb after the games.

Royal retired from coaching football in 1976, with consensus national championships in ’63 and ’69, because it was doing the same thing over and over, with only the players changing. The wins became expected and the losses hurt too much. But his love of words and melodies that move, and the people who create them never wavered.

“Darrell will do anything for you,” said Gatlin. “He drove me to rehab in December 1984 and saved my life.” When Willie’s house near Nashville burned down in 1971, Royal threw a private concert to raise money to pay his band, which was off the road and living in Bandera. Royal rented the Back Door, a joint behind Cisco’s Bakery, and charged $25 a couple, a huge amount back then. Nelson was astonished that the show sold out.

What’s more, the audience was pin-drop quiet when Nelson sang. Coach Royal, then the most prominent man in Austin next to Lyndon B. Johnson, made sure of that.

Texas “got” Willie, especially Austin. It was where he needed to be.

There was pressure from UT officials for the clean-cut Royal, who forbid his players from even wearing sideburns, to distance himself from the dope-smoking longhair who got the hippies and rednecks together at the Armadillo World Headquarters. But the coach wouldn’t hear of it. He saw the giving side of Nelson, who never smoked marijuana around Royal during his coaching days.

Royal hid a satisfying smile a few years later when, after Red Headed Stranger and Stardust made Nelson an international superstar, the same UT officials asked Royal if he could get Nelson’s autograph for them. “I don’t know him that well,” Royal told them, coldly, according to the book Conversations with a Texas Football Legend.

Tragedy hit the Royals in April ‘73, when 27-year-old daughter Mirian, an aspiring artist and mother of two, was killed when her car collided with a UT shuttle bus on W. 7th near Mopac. She was in a coma for 19 days before succumbing. Willie showed up at the Royals’ house but couldn’t find the words of solace until he played “Healing Hands of Time.” He’d sing it again for Darrell and Edith nine years later, after youngest son David died in a motorcycle accident a couple blocks from Mirian’s crash. A song could always reach Darrell Royal deeper.

When Willie’s oldest son William Hugh “Billy” Nelson Jr. committed suicide on Christmas Day 1991 at age 33, Darrell Royal did his best to comfort him. (Billy’s daughter Raelyn Nelson, who was four when her father died, rocked out on the recent Outlaw Country Cruise.)

Football and music. Golf and music. Words and music. With songs finding a home in his heart, there’d always been harmony in the remarkable life of the kid from Oklahoma who grew up to be a Texas football legend. Darrell Royal was coaching Austin, too, when he said, “listen up, everybody. You just might learn something.”

Correction: an early version misidentified the man, far left, in the guitar pull photo as Roger Miller. It’s Mickey Newbury. Also, that’s Steve Gatlin to Willie’s left.

Michael, I knew most of this, but it's the first time so much of it was in one place. I saw Willie sit in with some friends' band when he moved to Austin after the fire. At that point, I did not know who he was, until my friends began listing songs he had written. I was shell-shocked! Then I attended two of the first four picnics and was astounded! ... You made me smile, you made me laugh, you made me cry. You da man, Michael!

I had heard twisted versions of this from some twisted versions themselves. Never knew their friendship went so far back. Ray Benson told a story once about a night at the Armadillo after Mirian died when Coach came to a show. He felt like this was when the hippies and the rednecks first came together and accepted each other under the umbrella of the coach and the red-headed stranger. Also, that pic of Roger Miller looked like Bill Anderson at first. Bill wouldn’t be playing a nylon string guitar though.