David Garza plays for the man (not for long)

From Twang Twang to the land of Largo, the muse has him in the rear view mirror

If you were David Garza, early 2001 was the part of your career where you got up at 8 a.m. and went to a room at Atlantic Records and played your guitar and sang for an audience logged on to the label's Web site. This was when the big record companies were finally starting to embrace the internet, but they hadn’t quite figured it out. But when the 30-year-old Austinite went through that routine as a promotion for his new album Overdub, he found himself also playing for a congressman who was looking into the merger between America Online and Atlantic's parent company, Time Warner.

"I guess he wanted to see a musician in action as part of his investigation," said Garza, who was all too aware of the climate of legal touchiness in this era of Napster. "I'm sure his report compared me to T. Rex," he added with a laugh, referring to one of the many acts, including Prince, Bryan Ferry, Beck and Jeff Buckley, to which Garza found himself constantly compared, though not always in a complimentary manner.

Atlantic had won Garza’s services in a bidding war caused by a SXSW showcase at Steamboat in 1996. But five years, and two albums later, that deal was running on fumes. The critically-acclaimed 1998 LP This Euphoria did not sell, so Atlantic got handsy on the followup, which made control freak Dah-veed a little crazy.

Garza envisioned Overdub as a rock n’ roll record, with Living Colour’s rhythm section of bassist Doug Wimbish and drummer Will Calhoun on every track. "I wanted it to sound like a band record, rather than my usual style where, you know, here's a boombox recording from the bathroom and this one is outside with me hanging from a tree," Garza said. But Atlantic nixed that record and sent him back to the studio for 10 more tracks in which David plays all the instruments. They still didn't hear a hit, so Garza went back in and delivered "Say Baby," a cynical number about making concessions to radio. "Soul is a four-letter scam," he sings in his lanky falsetto, "the DJ won't spin your jam until you say baby, baby, baby, baby, baby."

Atlantic made it the single. This re-recorded album had almost no chance of breaking through and Garza could only throw up his hands.

"They treat the producer me differently than they do the artist me," Garza told me on the phone from the Lower East Side apartment he was being put up at for a month as he did the promo grind and lived for his weekly Wednesday solo gig at the Mercury Lounge. "As the producer I don't like to turn in a record and then be told it's not there yet. But as a songwriter I love another chance to get back in the studio." The label sends a car for the artist, but for the producer they only send tapes back for more work.

Wondering what happened to the creative control he was promised, Garza was bitter, but also understanding. Overdub had to sell or jobs were in jeopardy. "This is pretty much the ball game here," Garza said. "I'm working for AOL, dude. You think they want to lay back and give me a chance to organically grow as an artist?" And so Garza went where they told him to go and did what they told him to do, even if he sometimes didn't agree. They probably did the same shit with Foreigner.

When he sang "I was born in the shadow of a stadium" on the new "God's Hand," Garza was talking about Texas Stadium, former home of his beloved Dallas Cowboys and a couple of Texxas Jam concerts of yore. Garza's parents, who met as teen-agers in Rio Grande City and went to UT together, moved to Irving in '67, just after David's dad returned from Vietnam. He got a good job as a management consultant with the federal government and sent his four kids (David's got two older brothers and a younger sister) to Catholic school. "When I was in high school I begged my parents to send me to the Arts Magnet school (which would prep such talents as Erykah Badu, Norah Jones, Roy Hargrove, Edie Brickell and Earl Harvin), but they wouldn't hear it," said David, who evolved from metalhead to jazz prodigy in junior high. Every year in high school he made it to the All-State Jazz Competition in San Antonio as the best guitarist and would usually room with trumpet player Hargrove.

Another group of Magnet grads would have a big impact on Garza's formative years. "I used to hang around with Edie (Brickell) and the New Bohemians when I was 16, 17 years old," Garza said. "We'd jam for hours, man.” A scholarship to study music at UT brought David to Austin, where he would make an impact faster than you could say "Twang Twang Shock-A-Boom."

It was 1989 and Austin is still a college town. A period of overdevelopment and overextention in the mid-'80s had come to an end when the oil biz tanked, banks collapsed and the real estate boom went bust. Landlords were voluntarily lowering rents. Bands were living together in old houses in Hyde Park and musicians could get by on just one part-time job. It was a good time to be poor, this last glimmer of Austin Bohemia.

It was a good time to be David Garza, whose band Twang Twang Shock-a-Boom was a local sensation, selling out Liberty Lunch and moving carloads of their tapes. "To be 18 years old and playing with two incredible musicians (drummer Chris Searles and bassist Jack Haley) and getting the kind of response we were getting from the audience was just the best feeling," Garza said.

It almost made up for the backlash from longtime Austin bandwatchers, who couldn't understand how a trio of wide-eyed nouveau hippies and their songs about fish sticks and knobby knees could outdraw such established Austin acts as Jimmie Dale Gilmore, Lou Ann Barton, Poison 13 and Dino Lee. Critics were especially brutal. Suddenly, everyone was the scene treasurer, knocking Twang Twang for not paying their dues.

"I was definitely thought of as some sort of carpetbagger from Dallas," Garza said. "It was like you weren't allowed to have an audience unless you used to flip burgers at the Armadillo." Instead of breaking into the existing scene, Twang Twang became a scene unto itself. On their perfect Thursday afternoons, the all-acoustic trio would turn the UT's West Mall into a modern love-in, the fresh-faced followers singing along or clapping a rhythm for bongo man Searles to play off of. It was Up With People in Birkenstocks, a hootenanny with homework. Poi Dog Pondering had laid the groundwork for the busker paradise when they started playing on the Drag and in the West Mall a couple years earlier, but Twang Twang took it to the next level.

Columbia Records flew them up to audition in the boardroom, but the trio choked without their audience’s energy. They were still stars back home, but Garza quit in 1990, after just a year of Twangin’ and bangin’.

He wanted to do his own thing without having to consult with bandmates. But for awhile there, Garza looked like he had made a mistake of David Caruso-esque proportions. "There were only about 100 people there for my first solo show at Liberty Lunch and I kept wondering what happened to the other 900 people who used to come see us." He was ribbed for his insistence on using the Spanish pronunciation of his name, so Garza ran with it and called his band Dah-veed.

But if he seemed to have fun with the potshots on the surface, the criticism hurt deep down. "Every creative person has a fragile ego, but I couldn't let (the detractors) know they were getting at me," he said. I slung some arrows his way, but I didn’t think they were poison. After I’d written a glowing review of This Euphoria, I asked Garza if we were even yet. “I’ll let you know when the scars heal,” he said.

His shield was always the studio, where there was no one to tell him his lyrics were childish and his outlook inane. In the studio there was only the sound of his own voice and the work of his hands. There was also the road, where Garza could strut out from under the weight of preconceptions back home. Touring hard (he went through four vans in seven years) and writing prolifically, Garza was able to cultivate a cottage industry. Before there was Bob Schneider and his DIY ethic and gleeful genre-hopping there was David Garza, who has never let a grassroots approach mask his grand ambitions.

"He doesn't need all that pushing and marketing. He'll get it because that's what the major label people do. It's their jobs," said Craig Ross, whose association with Garza goes back to his production on an early Twang Twang cassette. "If it all fell apart tomorrow, if the major label deal went away and he had to start all over David would be fine."

It did and he was.

Overdub bombed and heads rolled and David Garza kept writing songs, kept producing records. He’s a music man, pure and simple.

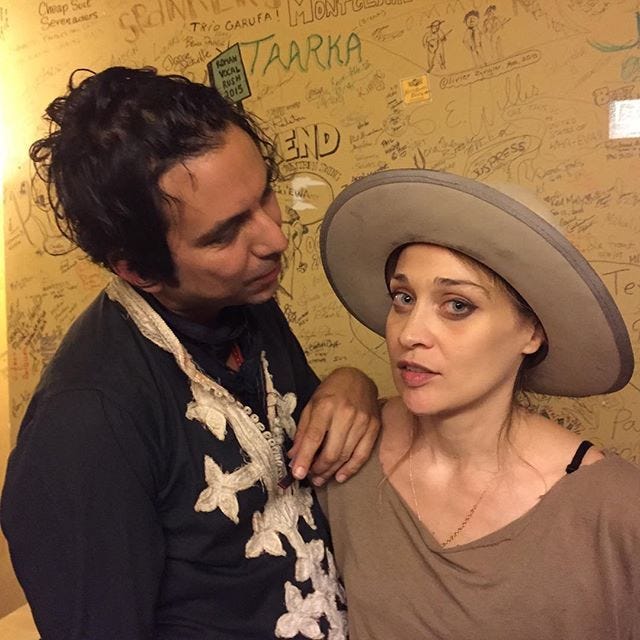

And last year a record he co-produced, Fiona Apple’s Fetch the Bolt Cutter, won the Grammy for best alternative album. Garza not only also played guitar, keyboards, percussion and sang background on the record Pitchfork called “an unyielding masterpiece” in a 10/10 review, he designed the album cover!

Garza’s association with Apple goes back to 2005, when he opened shows on her tour and also played in her band. He became a regular performer at hip Hollywood hangout Club Largo, where people like Jackson Browne, Chris Thile and his idol John Paul Jones of Led Zeppelin have sat in. He’s also toured with Gaby Moreno, playing piano and guitar, and produced the solo debut from Nina Diaz (Girl In a Coma) in 2016.

He makes the drive from L.A. to Austin, which will always be home, about three times a year because he finds it relaxing and creatively invigorating. The mid-point is his favorite recording studio- Sonic Ranch in Tomatillo, just east of El Paso- where he’s always welcome to record.

David Garza is as busy as he wants to be. When he was talking, in 2001, about people possibly losing their jobs if Overdub tanked, he wasn’t talking about his own.