Domino Records, Austin's first label of note

In the summer of 1957, ten Austinites took a night school course on song marketing at the YWCA on Guadalupe Street and ended up partnering with their instructor to start a record label and music publishing company. Each pledged $5 a week to meet expenses.

These moonlighting accountants and housewives and state workers and salesmen would put out regional hits from their office above a drugstore at 607 W. 12th St. and watch two of their acts — the Slades and Joyce Harris — lip sync on American Bandstand.

But by 1960, the original 11 label owners had dwindled to three. At the end of 1961, there were none.

This is the story of Domino Records, Austin's first label of note, which made some noise, but little money, in the years between the Elvis explosion and Beatlemania. It was an era when independent record labels flourished because, unlike the stodgy hierarchy-layered major labels, the children of Sun Records were quick to embrace rock 'n' roll as an exciting mix of black and white cultures.

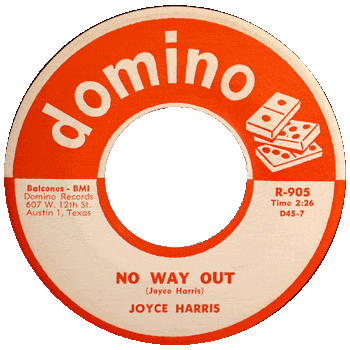

Domino went even further with Joyce Harris and the Daylighters: a white female singer backed by a black rhythm and blues band. Race was not an issue, however, because anyone who heard "No Way Out" (which critic Dave Marsh has listed as one of the greatest singles ever made) would swear the Etta James-like singer was black.

"I remember the first time we played together, thinking, 'Now this is what I'm talking about," said Harris, a New Orleans native who had cut several singles with her younger sister Judy at Cosimo Matassas' legendary recording studio in the French Quarter. "The Daylighters took me right back to the New Orleans thing."

The band was led by Smithville native Clarence Smith, who changed his name to Sonny Rhodes, switched to lap steel guitar and was still performing until he passed away in 2021. Rounding out the group were Willie Cephas on guitar, Ira Littlefield Jr. on drums, George Underwood on bass and Mack Moore on piano.

Harris and the Daylighters never played in public, only on records, so she was adamant about regular rehearsals before they stepped into the studio.

"One night, the Daylighters didn't show up, and so I got in my car and went looking for them," recalled Harris. There was a place over on "the Ends," slang for East 12th Street, where the Daylighters liked to hang, and sure enough the musicians were coming out of the White Swan when Harris pulled up. "Don't you remember, we've got a rehearsal?" she said. "Get in." But bandleader Smith and the other three hesitated. In Texas in 1961, black men didn't get in a car with a white woman, but Harris would have none of that. "Get in!" she said again, her tone amplified, and the band eventually complied, though it was an uneasy, slumped-down, drive across town.

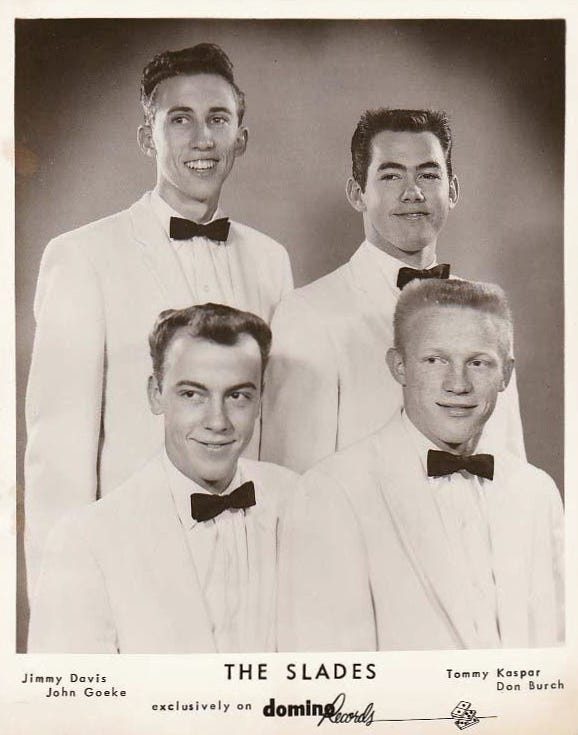

Though Harris and the Daylighters were the most flamboyant artists on Domino, the Slades were the label's signature act. A white doowop group of McCallum High students past and present, the Slades were the first artists signed to the label — on the basis of a live performance at a Girl Scout function, according to the liner notes of The Domino Records Story compilation, which was reissued by Britain's Ace Records in 1998. They were originally called the Spades, taking their name from a deck of cards, but when the group had a minor hit with first single "Baby"/"You Mean Everything To Me," several DJs in urban areas refused to play the song because "spade" was sometimes used as a racial slur. (Roky Erickson's first band was called the Spades five years later.)

Renamed the Slades, Don Burch, Tommy Kaspar and John Goeke, augmented by bassist Bobby Doyle, were poised for a national breakout in 1958 with "You Cheated." Initial pressings on Domino had sold more than 10,000 copies just in Texas, so several larger labels were circling for the rights. Hollywood-based Dot Records, which was doing well with Pat Boone, emerged at the top of a bidding war, but the night school record label project instead decided to release "You Cheated" on their own. They struck a deal with a Los Angeles "one-stop" to press and distribute the 45s.

"That decision led to the demise of Domino," said Ray Campi, a rockabilly singer signed to the label in 1958. It turned out that the one-stop had oversold its distribution capabilities, so while copies of "You Cheated" by the Slades were sitting in a warehouse, L.A. producer George Motola assembled a group of black singers, including Texans Jesse Belvin and Johnny "Guitar" Watson, to copy the tune note for note. To add to the confusion, the group was called the Shields. The cover version, distributed by Dot, beat the original to the charts, landing at No. 12 on Billboard. The Slades version stalled at No. 42.

Since Domino owned the publishing of the song, the company made money off the Shields, but the missed opportunity to break out its top act was demoralizing, said Joyce Webb, who sang backup on "You Cheated" and released several catchy singles under her own name on Domino. Webb, the 1958 Austin High prom queen, was discovered by Domino while lip syncing the hits of the day on Now Dig This! the Saturday morning show hosted by Cactus Pryor on KTBC, the only TV station in town at the time.

"We were all really in it for the fun at first," said Webb, who owned a glassworks business in Wimberley after her music career. "But then it started getting serious."

Campi said there was friction among the original 11 almost from the start. "You just can't have that many people making decisions for a label to be run right," he said.

The first to leave was Jane Bowers, the night school instructor who had achieved some success before Domino when Tex Ritter cut her song "Remember the Alamo." She took Doyle with her to Trinity, the San Antonio label she started with her attorney husband. That didn’t last, but Bowers hit paydirt writing five songs that landed on #1 albums by the Kingston Trio.

The last three remaining partners — Lora Jane Richardson, Anne Miller and Kathy Parker — relaunched Domino in 1960 with the idea to expand to country (Barny Tall), pop crooning (Rod McCullough) and R&B (Joyce Harris and the Daylighters). Unexpected cash came when the Fleetwoods covered the Slades' "You Mean Everything to Me" and included it on the B-side of million-selling pop hit "Mr. Blue."

Bowers was right about holding on to publishing.

"They were all songwriters or wanted to be songwriters," Campi said of the label founders, who regularly pitched their songs to the artists they signed. "Domino Records was like a family atmosphere," said Harris , who was signed to Domino after a friend of Richardson's saw her perform at La Macarena nightclub in Ciudad Acuña. "But looking back, I guess they didn't know as much about how to promote artists as I thought they did at the time."

Cash flow was always a problem at Domino, so when "No Way Out" attracted some interest, the tune was licensed to L.A.'s Infinity Records and Harris moved to the West Coast. Renamed Sinner Strong by Serock Records (a subsidiary of Scepter) and cast as "the female Jackie Wilson," Harris belted a couple more singles in the early '60s that didn’t hit. After recording a few sides for Eddie Bo's Fun Records in New Orleans in the mid-'60s, Harris got married and retired from the music business. She lives about 40 miles outside New Orleans and plays bluegrass music with her church group.

"It bothers me that so many people think Austin music started with the 13th Floor Elevators," said Campi, who moved to L.A. in 1959 and has taught in public schools there for four decades.

Austin was a small city in the 1950s, with Threadgill's on North Lamar Boulevard at the edge of town. It was a simpler, unjaded time, when 11 people could meet at the Y and ask "Why not?" The venture born in that night school seminar was not financially viable, but it sure seemed like fun for awhile.

Those night-school students with almost no experience in the music business can be proud of preserving some of the great sounds made in Austin before it became nationally known as a music mecca.