Bob Dylan and the Band. Allusive, majestic, snarling lyrics run through the organic groove grinder. The most important, influential songwriter in pop music history backed by four Canadians and a Southerner whose musical instincts and depth earned them the right to call themselves the Band.

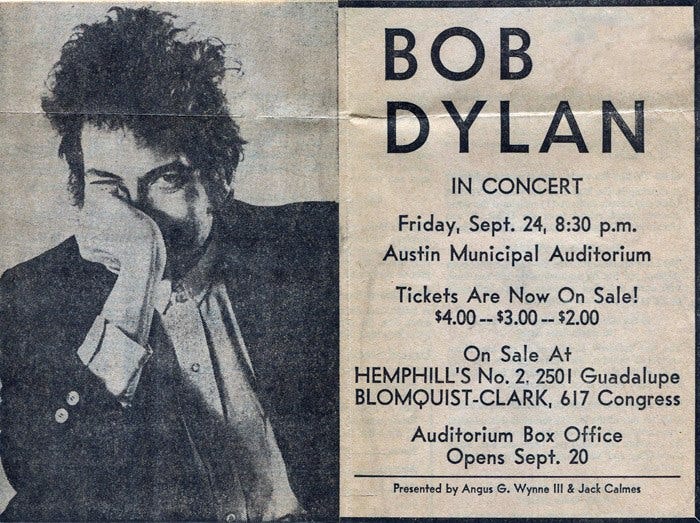

Forever entwined in rock music mythology, Bob Dylan and the Band were a magical combination that debuted right here on Sept. 24, 1965. Tickets were $4.

Later they would make enduring music together in the basement of a big pink house near Woodstock, but in 1965, 24-year-old Dylan and his mostly younger backing group were rock ‘n’ roll guerrillas on an artistic upheaval mission, slinging evil electric guitars in front of audiences who’d felt betrayed by the sound-over-message, trend-over-tradition shift.

Dylan opened his first Texas concert, a sold-out show at Austin’s Municipal Auditorium (later renamed Palmer Auditorium), with a solo acoustic set including “Gates Of Eden,” “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” “Desolation Row” and “Mr. Tambourine Man.” After a short break, he returned with Rick Danko, Robbie Robertson, Richard Manuel, Garth Hudson and Levon Helm — then called the Hawks — and launched into a loud, biting “Tombstone Blues,” followed by “Baby Let Me Follow You Down,” “It Ain’t Me Babe,” “Ballad Of a Thin Man” and the big hit at the time, “Like a Rolling Stone.” Dylan played the piano during “Maggie’s Farm,” the song that was practically drowned out in boos when Dylan and the earsplitting Butterfield Blues Band opened with it at the Newport Folk Festival just two months earlier.

“It was so in-your-face,” show promoter Angus Wynne recalls of the Austin electric segment. “You couldn’t really understand the words — quality concert sound systems were nonexistent back then — but you could feel the energy. It was like being knocked over by this huge burst of sound.”

In Austin, 1965 was the cusp between the beatnik generation and the hippies, but Dylan and the Band were basically playing what would later be called punk rock.

The Austin show was only the fourth time Dylan had played electric, and the first time he hadn’t heard boos from folk purists who pegged him as a pop sellout trying to glom onto the Beatles phenomenon.

“It never entered my mind — or heart — not to love the electric stuff,” says Stephanie Chernikowski, a former Austinite, now a top New York photographer, who was at the show. “Dylan and the Band were stunning. There were moments that felt like you were the only person in the room with them.”

Three months later, Dylan cited Texas audiences (he played at Southern Methodist University in Dallas the night after Austin) as among the most accepting of the tour.

But Gilbert Shelton, the “Fabulous Freak Brothers” cartoonist who was then a student at the University of Texas, had craved more exuberance from the Austin concert crowd. In an account printed in the November ’65 edition of Texas Ranger magazine, he described the audience as “mostly high school couples, all dressed up for church, almost . . . (who) sat like a bunch of toads, watching Bob Dylan rear back and shout, jump across the stage . . . waving around (his) Fender Jazzmaster electric guitar. . .”

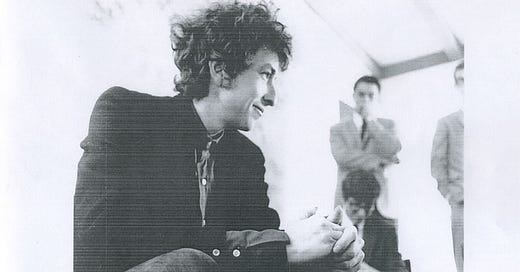

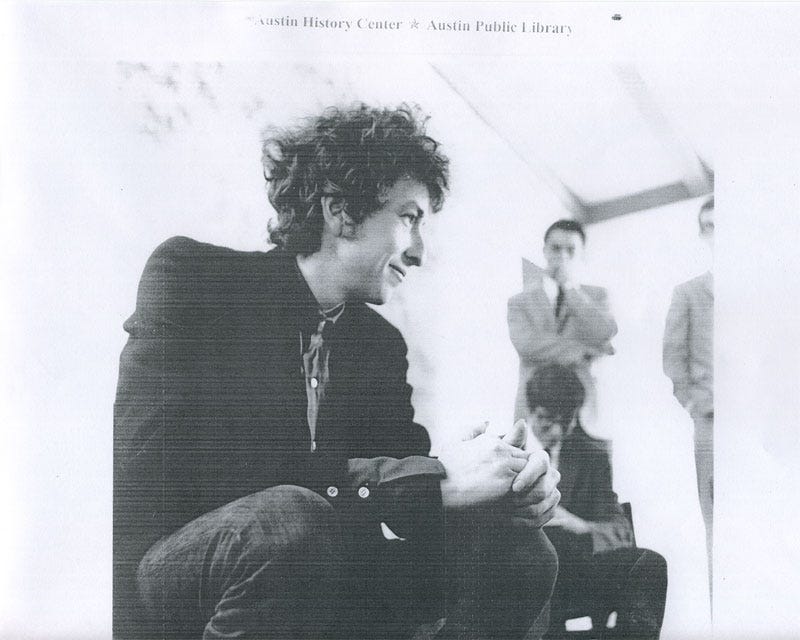

Shelton had met Dylan and the band, which he could tell “had recently joined Dylan because they still had their Canadian haircuts and clothes,” at the Villa Capri Motor Hotel on Red River Street the night before the concert.

Shelton describes a crazy scene of “go-go girls” from Dallas who just wanted to touch Dylan, a local beatnik turning up with cheap Mexican rum and a late-night listening session that ended with everyone grooving to Highway 61 Revisited, Dylan’s first all-electric album, which had come out three weeks earlier.

Wynne, a 21-year-old fledgling promoter, had decided to try to book Dylan in Austin and Dallas after repeatedly hearing “Like a Rolling Stone” on the radio after its July 20, 1965, release. “I looked at the back of a Dylan album and it said he was managed by Albert Grossman, so I called information in New York and got the number,” Wynne recalled. “When I called and made my pitch, someone yelled to the other room, ‘Hey, do you want to go play in Texas?’ and someone yelled back ‘Yeah, sure.’ ” That’s how things went back in the days before big-scale national tours.

Dylan had met the Hawks, the former backing band of Ronnie Hawkins, a year earlier through John Hammond Jr., whose father had signed Dylan to Columbia. They were reacquainted in August 1965, according to Clinton Heylin’s A Life In Stolen Moments: Day By Day 1941-1995, when Grossman’s secretary took Dylan to see the Hawks at a club in New Jersey. He hired away guitarist Robertson and drummer Helm, an Arkansas native, to play concerts in Forest Hills, N.Y., and the Hollywood Bowl that would showcase songs from the new album.

To avoid a repeat of the Newport Folk disaster, Dylan rehearsed his new band, including bassist Harvey Brooks and keyboardist Al Kooper, night and day for two weeks before the Aug. 28 Forest Hills Stadium show. He also decided to open with a 45-minute solo acoustic segment, followed by a set with the band, to ease the folkies into the new material. But the audience of 15,000 reacted just as negatively, with an estimated one-third of them booing lustily throughout the electric set.

The Sept. 3 Hollywood Bowl show, although sprinkled with hecklers, was more enthusiastically received. Still, Brooks and Kooper decided not to continue with Dylan. Kooper admitted, in an interview for Martin Scorsese’s stunning No Direction Home documentary, that he made up his mind to quit after seeing Dallas on the itinerary less than two years after the Kennedy assassination. “If they didn’t like the president,” Kooper said, with a laugh, “what would they think of this guy?” He had no intention of being Dylan’s John Connally.

Dylan flew up to Toronto on Sept. 15, nine days before the Austin show, to rehearse with the Hawks. Three nights later he was back in New York. The Hawks were ready.

Although Helm quit the group two months later, after musical disagreements with the front man (not to mention an aversion to being booed night after night), Dylan and the rest of the Hawks forged on to Australia and Europe with a series of fill-in drummers before settling on Mickey Jones of Dallas. Most of the audiences were contentious toward Dylan’s new musical direction, scenes of which dominate part two of the Scorsese documentary.

Then came Dylan’s motorcycle accident in July 1966, which, though not seriously injuring him, gave Dylan an excuse to lay low for a while.

During this period of mental healing, Dylan woodshedded daily with the Band, the informal sessions captured on an Ampex reel-to-reel tape machine. May to August 1967 was a summer of inspiration, as a relaxed Dylan started to get more of a feel for the Band’s earthy instincts. And the group had obviously been influenced by Dylan’s use of poetic license in his songwriting. The oft-bootlegged sessions (officially released in 1975) were called The Basement Tapes.

After blaring a hundred frantic solos a night behind Dylan’s spitfire lyrics (and the gritty Southern roots of Ronnie Hawkins before that) the Band, off the road for the first time in years, fell into a more unforced approach to collective song making, and painted the masterpieces Music From Big Pink (1968) and The Band (1969).

When Dylan toured again, almost eight years after his 1966 world tour ended with the legendary concert at London’s Royal Albert Hall, his backing group was once again the Band. This time they weren’t anonymous sidemen but artistic peers.

Bob Dylan and the Band opened their 1974 tour with two sold-out shows at Chicago Stadium, the Band performing “The Weight” and “The Night They Drove Ol’ Dixie Down” right alongside Dylan classics no longer burdened with acoustic/electric distinctions. Their hurried debut, on Sept. 24, 1965, in Austin, must’ve seemed like a hundred years ago.