The negative things in your life become positive over time. At least that’s how it turned out for me.

My mother was diagnosed with cancer in 1973, my senior year of high school, and she passed away near the end of my freshman year of college. My grades resembled the downward chord progression of “House of the Rising Sun,” and after dropping out I started living the lyrics of a poor boy, ruined.

Homeless at 18, I squatted for a couple months in an old airplane hangar in Pearl Harbor, where I worked as a gym attendant. Then all us kids, besides Marty, the youngest, were shipped off to Long Island to live with relatives until my father divorced his Parents Without Partners grifter, which took about a year. Like Sister Mahalia, I look back and wonder how I got over.

But if all that turmoil didn't happen, I wouldn’t have been raised by Kate Hellenbrand and Michael “Rollo” Malone, a couple from New York City who bought Sailor Jerry’s tattoo shop in Honolulu in 1973.

While my mother was alive I was still a virgin, of course, and had never done drugs, not even alcohol. That would soon change like the weather during typhoon season.

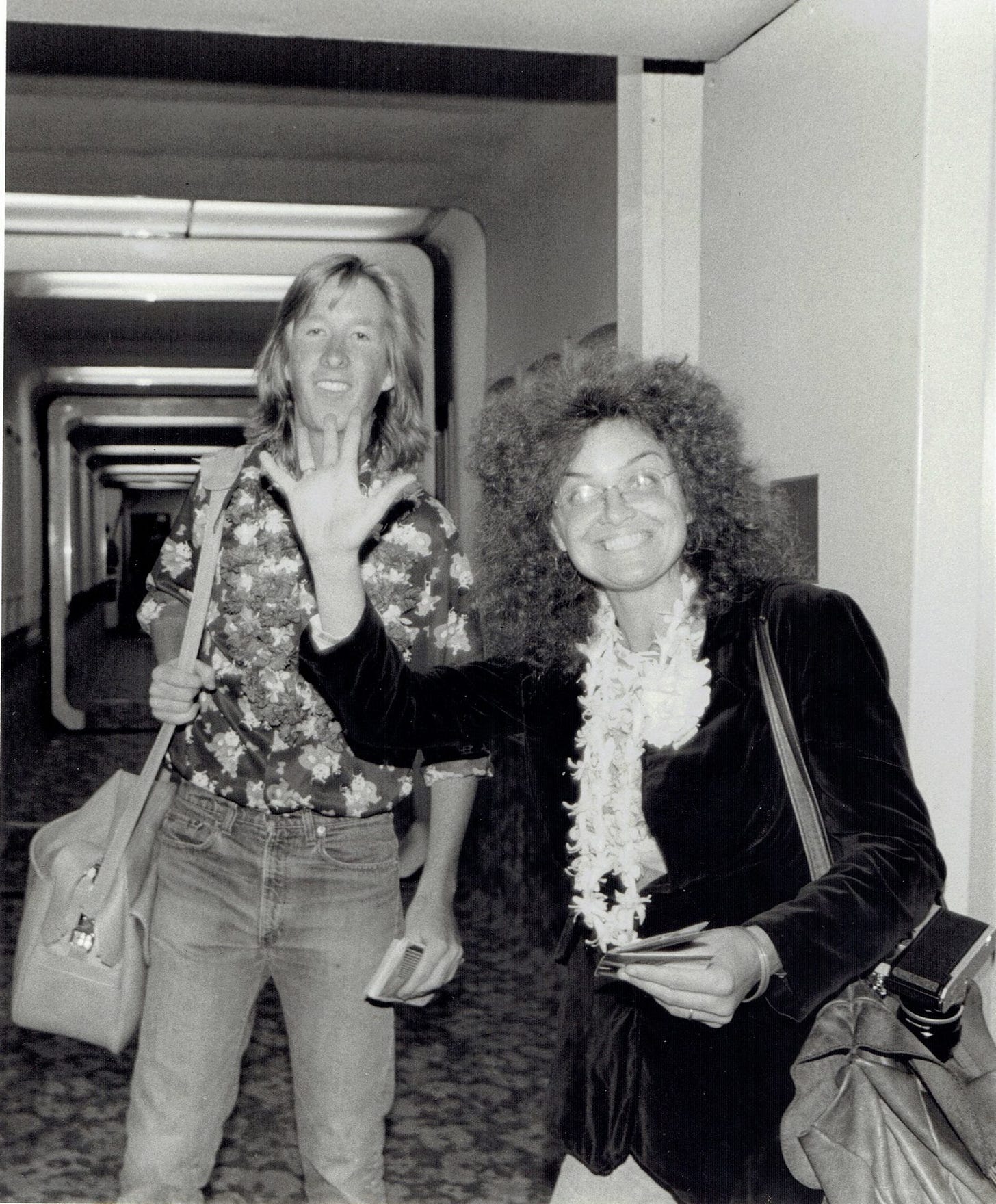

The period of debauchery, now entering it’s fifth decade, started when I sent an unsolicited Aerosmith concert review to Sunbums magazine, Oahu’s counterculture rag, in Dec. 1974. The show had already been assigned, but the editor called me and said to come down to the office to talk about being a contributor. And there across the desk was this 31-year-old streetwise hippie with a faux-fro and an electric smile. Me and Kate Hellebrand were pretty much inseparable the next year or so, as her live-in boyfriend Malone worked ‘til midnight in Chinatown, and Kate needed a running buddy.

Hellenbrand had taken over Sunbums from a popular married couple who had founded it, and there was a lot of grumbling when she made changes, like bringing in a University of Hawaii professor for highly-analytical film reviews. This had been a surfer lifestyle rag! But Kate’s titanic personality eventually got everyone on board. She didn’t butcher your articles, or really even line-edit, once returning a 2,500-word draft of my first cover story, with “Write this better!” at the top of the first page. Which pissed me off until I re-read it.

I did a couple record reviews, but I told Kate I didn’t feel qualified. I’ve never played a note of music, and my tastes were mainstream, not hip. Then she gave me liberating advice I’ve carried through my whole career: “If you can’t be good, then be bad.”

Rollo tattooed a guy who worked at the airport stocking first class cabins with food and beverages, so their refrigerator on Liliha Street was always full of Michelob, filet mignon and lobster. They’d host visiting tattoo artists from all over the world, and there were big dinner parties where I was the only un-inked guest. One night Thom DaVita from the Lower East Side announced that he wished he was gay. Well, that squashed the small talk! “In my neighborhood they just busted 200 guys having sex at 5 a.m. in an old warehouse,” he said. “Can you imagine how great it would be if that’s what you were into?” Rollo added, “yeah, we’re stuck with women, whose idea of kinky is screwing with the lights on.”

What a glorious world I stepped into! Sunbums was a pot, beer and coke party for 13 days, then a brutal all-nighter when we put the paper to bed. I’d drive, frantically over the mountains to the printer in Kaneohe, as Kate would proof the pages, then run in with her big haole breasts to apologize for being two hours late. Every single issue was delivered this way.

Kathy, as I knew her, was the most fascinating person I’d met in my 19 years, by Secretariat lengths. I didn’t tire of her stories until years later, when I realized many of them started with a description of her outfit at the time. (I don’t care what shorts and top you wore when you saw James Brown in L.A. right after the Watts riots!) Since I was broke and she had Rollo’s cash, Kate paid for everything and never made me feel guilty. I went from having no friends to having the best one ever.

The first time I got stoned was driving over the Pali Highway with K and Sunbums associate editor Leilani, going to see Blazing Saddles. Leilani’s other job was street prostitute, with a black pimp, so she lost her shit on all the movie’s racial stuff. The three of us were howling uncontrollably to the point that the usher came to ask us to please keep it down. At Blazing Saddles!

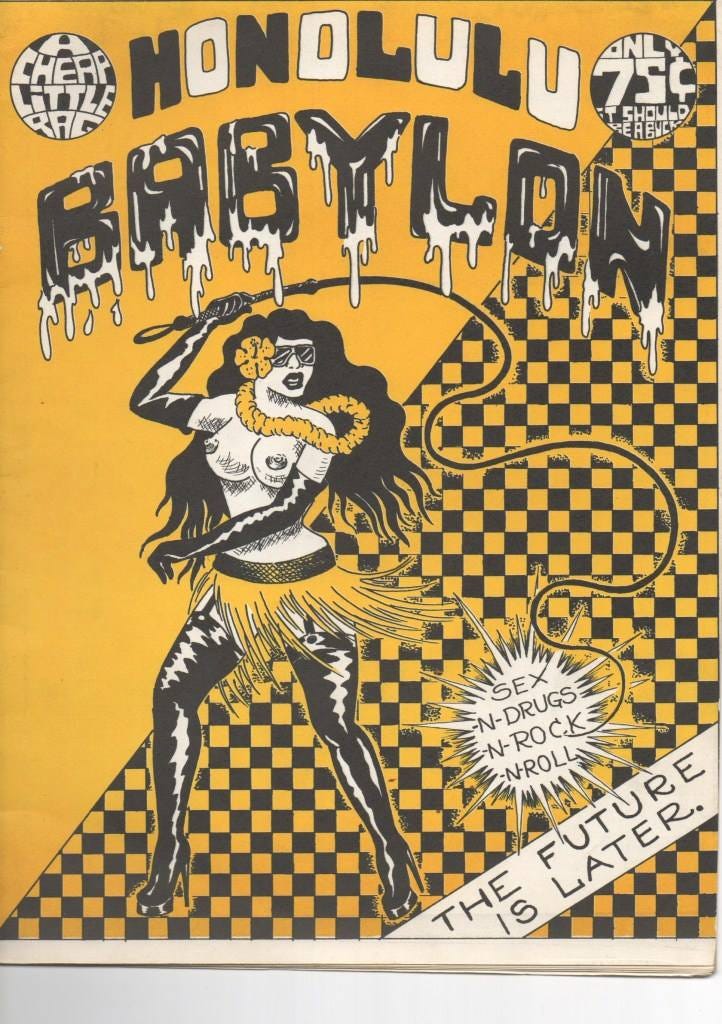

After Hellenbrand and Malone had a bad breakup in ’76 and she moved away, I felt like the child of divorced parents who was closer to the other one. But Malone and I eventually got tight putting out the scandalous Honolulu Babylon zine. We took pseudonyms- Yikes! Crawford and Rollo Banks- so we wouldn’t get sued. Or beat up.

Over our next seven years as friends and roommates, Rollo became my greatest teacher- a man of letters who couldn’t write. He called me his typist, but I was smart enough to put up with the insults because I was learning to become more interesting.

Rollo taught me to never use cliches, like “when pigs fly” or “not my cup of tea.” He'd go into a big windup about how something would happen only "when the little bacon butts are stacked up over LaGuardia." When I wrote that a band’s music was “not my mug of Sleepytime,” that was straight Rollo.

I remember one day at the grocery store we were in tears laughing so hard as we perused the cheese section for "who cut the cheese?" variations. Who parted the provolone? Who gouged the gouda? Who broke the brie? Who choked the cheddar? Who carved the camembert? Who mangled the mozzarella? Grown men giggling like lunatics.

Rollo had a t-shirt business on the side- Mr. Lucky’s- which is what brought us to Austin in ’84. I was the lone employee, handling everything besides the designs, which Rollo based on tattoo motifs like the Grim Reaper and wizards and unicorns. Harley Davidson had discontinued its skull designs on t-shirts in favor of a more family-oriented image, but bikers still wanted the badass stuff, and that’s what Mr. Lucky had.

The business took off in Honolulu after we ran ads in Easyriders and Outlaw Biker magazines, and started receiving 10-20 orders a day. One thing we didn’t fully calculate was how much time and money it would take to mail the shirts. We were charging $10 each and they were $3 to ship, because everything from Hawaii had to go first class. There was never not a long line at the Chinatown post office, where immigrants would send money orders and packages home.

We started talking about moving the company, and Rollo's tattoo business, to the Mainland. But where?

Austin was on my geta-waydar after I got a postcard from my friend Andrella, who was on tour with the Cramps (her boyfriend was guitarist Bryan Gregory), and she said the band had just played a great show at a club called Raul's in Austin. “You wouldn’t believe this was Texas,” she wrote. I knew the great critic Lester Bangs lived in Austin for awhile, so I figured stuff must be happening.

Then Rollo received a newsletter from his old friend Travis Holland, who he’d known since his Jerry Jeff Walker days in NYC. Holland’s Dallas County Jug Band (with Steve Fromholz), was based in Austin. Coincidence or omen?

Middle of the country. College town. Music town. And a river runs through it. Austin just felt right, so, after an exploratory week in ‘83, we moved operations the next year. The second location of Recycled Records was moving out of an old white house at 2712 Guadalupe that had a shoe repair shop in the front, so we took it for China Sea Tattoo and Mr. Lucky T-shirts. It was a shit location next to Burger King with no parking, but, as luck would have it, the Austin Chronicle moved to 28th and Rio Grande, two blocks away via the back alley. There was a steady stream of visitors, as Rollo was always up for holding court, especially since there was no tattoo business in Austin to speak of, back in the ‘80s.

Just like with Honolulu, Rollo loved Austin and despised Austin, which he called “the little town with the big head.” He mocked the worship of musicians here and made me write down some of his Rolloisms, like "life is what we do because we can't play the guitar" and "once you put on the clown suit, you can't take it off." The latter was aimed at Dino Lee, the theatrical rocker who tried to play it straight one night at Steamboat and got cracked in the head with a shot glass. Rollo met Margaret Moser when she was one of Dino’s Jam & Jelly Girl backup singers. They married a few months later, in Dec. ’84.

Rollo was not the kind of guy that ever went for sentiment. When his close friend, T-Birds bassist Keith Ferguson, died from drug-related causes in 1997 at age 50, Rollo remarked that one thing he always admired about Keith was that he accepted his addiction and never whined about needing to stop. He was a man about it. Ownership of your actions, good or bad: that was big with Malone.

When Margaret told me that Rollo had shot himself in Chicago (April 2007), I started thinking about what might’ve been going through his mind at the time. It never dawned on me that he was depressed. He’d had mounting health problems and it was just "time to check out," as he scribbled in his suicide note. We all have to die sometime, and Rollo was not going to let anything else decide his date. He was a man about it.

Hellenbrand became Shanghai Kate, “the Godmother of American Tattooing,” and has lived in Austin since about 2008. Her lust for adventure inspires, but two nasty bouts with Covid left her bed-bound for much of 2022. I’m 66, so that makes her 78.

I may be an orphan again. but I’ve always had music. It’s the answer to the God riddle: all-knowing and all powerful. Inside all of us. Always was and always will be. Whatever I was going through, there’d be a song on the radio that would tell me what to do. “Slip Sliding Away” by Paul Simon convinced me to quit a good job that made me miserable. “When a Man Loves a Woman” urged me to give a souring relationship one more try. Good songs sometimes lead to bad decisions- as in those two cases. But at least you don’t feel all alone.

Where would I be without Kate Hellenbrand or Michael Malone? Maybe I still would’ve found Austin, but I wouldn’t have been the person waiting for someone to fart so I could say, “Who lanced the limburger?”

I’d still have been a writer, but not one who sees “Write this better” in the upper right corner of every half-assed draft I was ready to turn in.

I dedicate this book to my mentors, who were also my dementors, praise the lord. The best time to get lucky is in your darkest hour.

After so many great stories on the Austin scene, it's so good to learn more about you, the teller of them. Bravo!

Interesting narrative on how you fell into rock journalism. My background was not as challenged as yours (both parents, graduated Baylor University, straight white guy) but I recall the day I went into the Buddy offices to try and sell Stoney Burns some photos I shot of Jerry Jeff Walker in concert. A job was offered, and 8 years of "living in sin" followed.

There are no regrets.