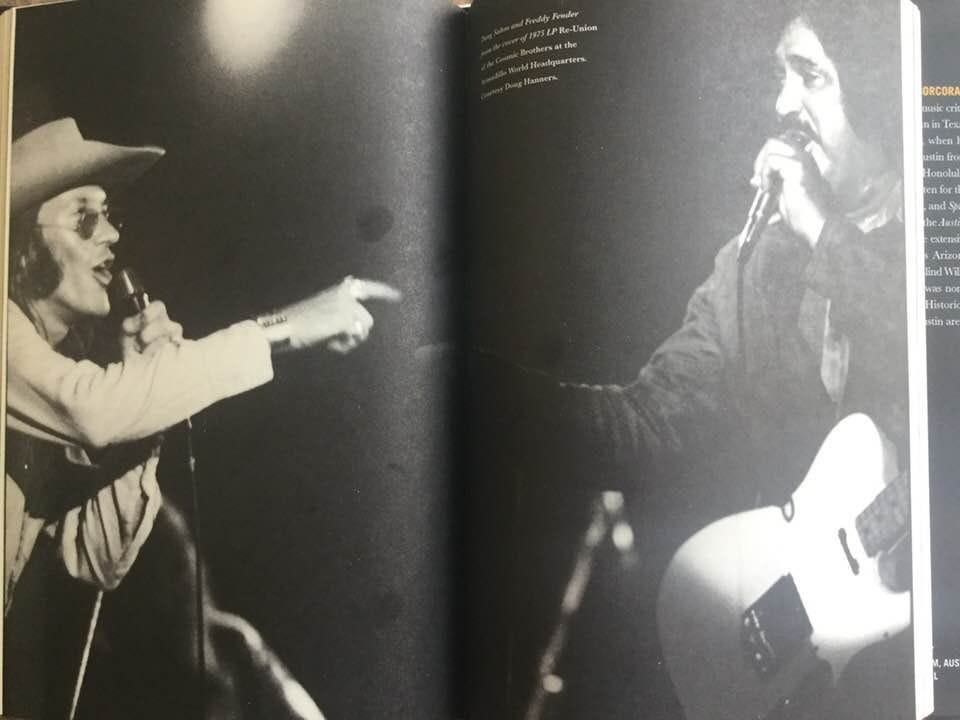

Doug Sahm and Freddy Fender in All Over the Map: True Heroes of Texas Music

When Doug Sahm recorded “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights” on his 1971 Tex-Mex roots project The Return of Doug Saldaña, the track opened with a salute to the man who wrote it. “And now a song by the great Freddy Fender,” Sahm said, his voice drenched in echo. “Freddy, this is for you, wherever you are.”

At the time, Fender was working as an auto mechanic and occasionally playing beer joints in the Rio Grande Valley.

A teenaged Sahm used to follow “El Be-Bop Kid,” as Fender was billed, all around Central Texas in the late ’50s. But the pair, who would comprise one half of the Texas Tornados in the ’90s, didn’t meet up again until 1974, when word of Sahm’s cover made it down state.

Rediscovering the voice of the Valley, Sahm convinced Fender that a nice payday awaited him at the Soap Creek Saloon, off Bee Cave Road in West Austin. To ensure a full house, Sahm opened the show.

“When we pulled into the parking lot, there were all these hippies in cowboy hats, passing around joints,” Fender recalled in 2004. “I thought, ‘man, what has that crazy guero gotten me into?’”

But Freddy knew, as soon as he walked onstage to insane applause, that the night belonged to him. His mix of gritty bar band rockers and bilingual romantic ballads were greeted with such jubilation that Fender was convinced to re-focus on his musical career. Things were finally going right for him after that deuce in Angola (LA) State Peniteniary for marijuana possession in the early ‘60s.

Fender got with with Sahm’s producer Huey Meaux, also recently back from a stint in prison, for pimping a 16-year-old Houston girl to D.J.’s at a country music convention in Nashville. Meaux signed the singer to his Crazy Cajun label and asked him to cover country song “Before the Next Teardrop Falls,” but Fender was hesitant. “I can’t sing that gringo shit,” he told Meaux, but the producer was insistent, even though the song was damaged goods, having already flopped for Duane Dee (1968), Jerry Lee Lewis (’69) and Linda Martell (‘70). When Meaux heard Freddy’s tender vibrato on the song in his mind, he saw a worldwide No. 1 smash- and he was right.

Huey P. Meaux’s middle name Purvis would prove fitting in ’97 when he pleaded guilty to charges of sexual assault of a child, drug possession and child pornography and ended up serving 10 years in prison. But he was also a music business genius, whose maneuvers in the ‘60s and ‘70s set up Sahm and Fender for long careers.

The bi-lingual “Teardrop” topped both pop and country charts, coming out of car radios and jukeboxes in every neighborhood, from the barrio to the country club. Suddenly, the lisping Chicano mechanic was the hottest “new” singer in the country, winning Billboard magazine’s male vocalist of 1975, while “Teardrop” won the CMA Award for single of the year.

The followup was a re-recording of “Wasted Days,” which also hit No. 1, as did “Secret Love” and “You’ll Lose a Good Thing,” the Barbara Lynn cover. If not for what happened at Soap Creek, Fender might’ve still been fixing cars. “This is for you, Doug Sahm, wherever you are,” Fender said in the intro of an album version of “Wasted Days.”

With Dallas native Lee Trevino the reigning PGA Champion, 1975 was a good time to be a Mexican-American from Texas. Both Freddy and Lee (also ex-Marines) were struck by lightning, but in the case of Trevino it was literal. “Even God can’t hit a one-iron,” he joked about holding that club over his head during lightning, but he was struck during the Western Open and suffered a bad back injury.

In Fender’s case, it was more like a lottery win than a lightning strike. His triumphant recasting as a country balladeer was one of several times he started over in a career that took him from the cantinas to the casinos, county fairs to European festivals, from the slammer to the Grammys. After his prison term ended in ‘63, Fender moved to New Orleans, working at a shrimp factory and moonlighting as an R&B singer on Bourbon Street. He could sing a ballad like Aaron Neville, who had a smash hit in 1966 with “Tell It Like It Is.” But Fender’s family was homesick and he was soon back in the bars of the Rio Grande Valley, playing Tex-Mex rock and blues.

His champion Sahm (b. 1941) was also not one to stay in one place, especially musically. A child steel guitar prodigy, who sat in Hank Williams’ lap in Sept. ’52 in San Antonio, Sahm became a rocker after Elvis, recording “A Real American Joe” b/w “Rollin’ Rollin’” for Sarg Records of Luling in 1955. Several more Little Richard-influenced 45s came out on tiny regional labels in the ’50s.

Neighbor Homer Callahan got a teenaged Sahm hooked on the blues, bringing over records by Howlin’ Wolf, John Lee Hooker and Lightnin’ Slim. Callahan was old enough to get into S.A.’s Eastwood Country Club to see the likes of T-Bone Walker, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown and Bobby “Blue” Bland, but Sahm had to sneak in. He also frequented Latino clubs on the West Side, where most rock bands had vibrant horn sections. The kid had a big appetite for anything with grit and soul.

“The Beatles had Brian Epstein,” Sahm told the Houston Chronicle in 1989, “I had Huey.”

During the British Invasion of the ’60s, producer Meaux saw the rhythm of “She’s a Woman” (1964) by the Beatles as a twist on the conjunto beat and created the template for a new Tex-Mex garage rock sound. He named Sahm’s new band Sir Douglas Quintet and posed them as Brits, but that ruse was abandoned after the first national TV performance of breakout hit “She’s About a Mover” showed three Hispanic members. Also in 1965, Dallas’ Sam “the Sham” Samudio put out “Wooly Bully,” and the next year a Michigan band of Latinos named ? and the Mysterians topped the charts with “96 Tears.” The Tex-Mex organ sounded like a cash machine to Meaux.

After “Mover,” SDQ released the moderate hit “The Rains Came,” then the raid came. The band was busted for marijuana possession in Corpus Christi in late ’65, just as their career was taking off, so while that was being dealt with, Sahm and company scattered. The bandleader landed in San Francisco, where he fell in with the Grateful Dead, fellow Texpatriate Janis Joplin and like-minded roots rockers Creedence Clearwater Revival. The SF lineup of the Quintet, which included Sahm, Meyers, bassist Harvey Kagan, saxophonist Frank Morin and either Johnny Perez or Ernie Durawa on drums, found an admirer in Bob Dylan, who wrote “Wallflower” for Sahm.

But in the early ’70s, Sahm rejected the poisoned Haight Asbury scene and came back to Texas to re-establish himself as a barroom rocker with The Return of Doug Saldaña. The groove was back in town! Sahm gave the Austin club scene its soul, with fluency in every style of Texas music, from blues and conjunto to Cajun, honky-tonk and psychedelic rock. Being in his presence was to be linked to the days when Lightnin’ Hopkins and Freddie King played juke joints, Ernest Tubb’s tour bus hit every honky-tonk in Texas, Aldolph Hofner had the most Western swingin’ polka band in the land and Huey P. Meaux hummed future hits while he cut hair at his barber shop in Winnie.

Sahm was a man with his feet always in two different places. He loved Austin, but he was a San Antonio boy. He chain-smoked pot, but was an avid fan of baseball, the American Pastime. He loved Hank Williams and Hank Ballard equally.

Besides facilitating Fender’s rebirth, Sahm was instrumental in getting a mentally troubled Roky Erickson back in the studio after the former 13th Floor Elevator singer’s release from Rusk State Hospital in 1972. “Red Temple Prayer (Two-Headed Dog),” the single Sahm produced in ’74 by Roky and the Aliens, proved that whatever deranged demons ravaged Erickson’s cerebrum, he remained a tremendously soulful singer and songwriter.

When former Austinite Bill Bentley was putting together the 1990 all-star Erickson tribute album, Where the Pyramid Meets the Eye, he saved a plum for Sahm, letting him and his sons Shawn and Shandon have “You’re Gonna Miss Me.”

Sahm’s death at age 58 of a heart attack in a Taos, N.M., motel room on Nov. 18, 1999 broke Austin’s heart. When the news hit, musicians gathered at Antone’s for an impromptu tribute, and radio stations including KGSR-FM and KUT-FM played Sahm’s music around the clock.

The turnout at his funeral, on the West Side of S.A., attested to Sahm’s wide-ranging appeal. The crowd was so large that about a third of the estimated 1,000 on hand had to huddle around an overwhelmed loudspeaker outside. But even more impressive than the number of mourners was the way they cut across all lines of age, race and social standing. Not only was just about every Austin and San Antonio music veteran on hand, but those who came to pay their respects included bikers, field workers in their best pair of jeans, club owners, music executives and fans from as far away as Holland and Canada. They wore black cowboy hats or Chicago Cubs caps in homage to the cosmic cowboy whose passion for life was infectious. And when they approached the coffin, after waits as long as an hour and a half, they touched the trademark black hat that Sahm was buried in and slipped in little gifts — guitar picks, joints, poems.

“It’s like they burned the encyclopedia of Texas music,'' said Joe “King” Carrasco, whose “nuevo wavo” sound owed a huge debt to the music Sahm and Meyers made with the Sir Douglas Quintet. With Sahm gone, the recent past seemed like ancient history.

Conspicuously absent was Fender, who didn’t always get along with Sahm after they were in the Texas Tornados. Sahm was a notorious motormouth, talking baseball or enchiladas through a cupped hand in loud bars, and Fender was more reserved. One was Mexican-American and the other one wanted to be, but their upbringings couldn’t have been more different.

Baldemar Huerta, as Fender was born on June 4, 1937, labored beside his migrant worker parents in the cotton fields of Arkansas and the beet farms of Michigan as a boy. Back in San Benito during the winter months, he’d sit outside Pancho Galvan’s grocery store, plucking a backless, three-string guitar.

At age 10, he made his first radio appearance, singing “Paloma Querida” on KGBS (later renamed KGBT when co-owner Genevieve Beryl Smith became Genevieve Beryl Tichenor) in Harlingen. Figuring the barracks beat the barrio, Fender joined the Marines at age 16 and came out three years later with dreams of becoming the first Chicano rock ’n’ roll star. His specialty was putting the big hits of the day to Spanish lyrics and El Bebop Kid had a regional hit in 1957 with “No Seas Cruel,” his version of Elvis Presley’s “Don’t Be Cruel.”

When he signed to Imperial Records, the home of Fats Domino, in 1958, he became “Freddy Fender” after his favorite guitar. “Just think,” Fender joked in 2004, “if I had been playing a Yamaha guitar, I’d be the number one act in Tokyo.”

While out on tour in May 1960, Fender was arrested for possession of a small amount of marijuana in Baton Rouge, La. He served two and a half years, but was able to use that time to inform his performance in the 1977 prison film Short Eyes.

The nightclub lifestyle had its grip on Fender through his successful years and in 1985 his wife Vangie dropped him off at a substance abuse treatment facility. But he was sober the final 19 years of his life. Fender passed away in 2006, four years after his daughter Marla donated a kidney to him.

Near the end came one of Fender’s proudest achievements, inclusion in the book Above and Beyond as one of the Top 100 former Marines who’ve conquered civilian life. It’s an honor that drew laughter from the former hot-headed recruit.

“I’d love to buy a copy for every drill sergeant who kicked my ass,” he said.

The history of Texas music is one of glorious intersections. Sometimes it’s the style of music, like when polka became conjunto and jazz became Western swing. But much more often, it’s the musicians whose meetings change the course. South Central Texas homeboys Doug Sahm and Freddy Fender elevated each other because they were of the same soul.

I recorded the albums after Before the Next Teardrop Falls - Are You Ready For Freddy, Rock N Country and If You're Ever In Texas after I moved back to Ft Worth in 1974. Doug would come in every so often with a big glass vile of some herb but mostly it would be Freddy's sessions. Did a session with Kinky Friedman too. But I didn't know their entire history. When Freddy went back to the Valley however after his Louisiana time, he would go to various recording studios and record "masters" for them and when Teardrop Falls hit, the owners of the masters contacted Huey and he had to buy them all up so they wouldn't be released. There were dozens of recordings we overdubbed new tracks on, many of them the same songs at different studios. Thanks again for the stories, Michael...

I was at Soap Creek when Freddy played there. He looked totally out of place with a leisure suit on and had kind of a skeptical look on his face at first, but he got into it once he felt the crowd response. I remember him play with Doug at the Armadillo too. Cherry Pie was one song I remember.