From Pecan to Dirty Sixth: History of Austin's "Street of Dreams"

Sixth Street gave us Antone's, Steamboat, the Black Cat, and 18 decades of history.

Austin’s most famous street has earned the nickname “Dirty Sixth” over the past few years, with an unruly Bourbon Street-like atmosphere and a YouTube driven reputation for violence. It’s where teens from Killeen beef with bullets on weekends, and sometimes the scent of danger makes you forget the history of the street whose majority of buildings, even those housing tattoo parlors and frat bars, were erected in the late 1800s. East Sixth, from Brazos to Red River Streets, has the greatest concentration of limestone Victorian commercial buildings west of the Mississippi.

The close proximity of nightclubs on Sixth, many of which change to live music venues for a week to catch a whiff of the windfall, was a key to the appeal of South by Southwest in the early years. Modeled after Manhattan’s New Music Seminar, SXSW had a big logistical advantage in that music industry attendees could see bands in clubs a few steps from each other all the way down Sixth and up Red River Streets. It was possible to sample 10 acts in a couple hours. Equal exposure in NYC would require several cab rides and all night.

The ‘80s and ‘90s were the heyday for live music on Sixth, with the Black Cat and Steamboat rockin’ a block apart, and the Cannibal Club across the street. You had reggae at Flamingo Cantina and punk at Emo’s and blues at Joe’s Generic and country at Headliners East and Irish music at B.D. Riley’s and Maggie Mae’s, and everything in-between at Babe’s and Lucy’s Retired Surfers Bar. And that’s only half of it.

But it was still tame enough that the Coen Brothers could make their first film Blood Simple undisturbed on Sixth Street in 1984. Three-time Oscar winner Frances McDormand also made her screen debut, with her character moving into an apartment above the Old Pecan Street Cafe (314 E. Sixth) that was the scene of the bloody finale.

By the ‘90s, “Dirty Sixth” had gotten so popular that the street was closed to cars on weekends and during SXSW, which created a hangout for teenagers too young or adults too broke to get into the bars. The mob that mills between the barricades triples during South by Southwest, calling for cops in riot formation. SXSW lost Sixth Street around 2010, when the biggest names in hip-hop, from Jay Z to Kanye West to Lil’ Wayne and Eminem, started coming to South By. And the word was you could see them for free. Fans from all over the country RSVP-ed to parties they’d never get into, but when they got to Austin they discovered that the real action, the “parking lot pimpin’,” was in the closed-off street. It was a free venue which didn’t have a dress code or capacity limits. But when anything goes everything went.

I started avoiding Sixth during SXSW five or six years ago, when I gave up trying to see a band that was just two blocks away. I don’t think vintage Earl Campbell could’ve made it through that crowd. The few miserable-looking, badge-wearing registrants moved through the roving street gangs and drunken frats like they were navigating chest-high swampwater. This was not in the brochure!

Some Sixth Street merchants and club owners made news in 2013 when they closed and boarded up the Saturday night of the Texas Relays track meet, the Super Bowl for Black Austin. Their venues didn’t cater to that predominantly teenaged crowd and none of their usual customers could get through the throng, they argued, but the moves smacked of racism.

History reminds us that Sixth Street, which was platted as Pecan Street in 1839, was built on true diversity. While the rest of Austin abided by rules of Jim Crow segregation, East Sixth was always open to every race. Black businesses were next to Lebanese, Chinese, Jewish and Hispanic storefronts. Jonas Silberstein’s store at

305 East 6th St. was one of the few in Austin where blacks could try on clothing before they bought it. White businesses, like Hyman Samuelson’s Crown Tailors at 408 E. Sixth, advertised on Black radio shows, such as Lavada Durst’s “Dr. Hepcat” on KVET. “Now if you want to be draped in shape and hep on down, get your frantic fronts at Crown,” Durst would say.

The Academy retail chain’s second outlet was a military surplus shop at 223 E. Sixth. Twin Liquors grew out of Jabour’s Package Store. And Austin’s first J.C. Penney’s was in the building at 204 E. Sixth St. where Alamo survivor Susanna Dickinson once ran a boardinghouse on the second floor, while her husband made caskets on the ground floor. This info from Dr. Allen Childs, whose family owned Kirby Shoes, and who wrote a Sixth Street history book.

Sixth (Pecan) Street became Austin’s east-west Main Street because it was the most level path from the east. And it was the closest street to the Colorado River that didn’t flood in the years before a dam was constructed in 1893. It was safe to build on well-traveled Sixth Street and so settlers and immigrants opened dry goods stores and saloons and sporting houses and hotels. When the Houston and Texas Central Railroad came to Austin in 1871, the town’s population doubled to 10,000 in a year. Pecan Street was dubbed “The Street of Dreams.”

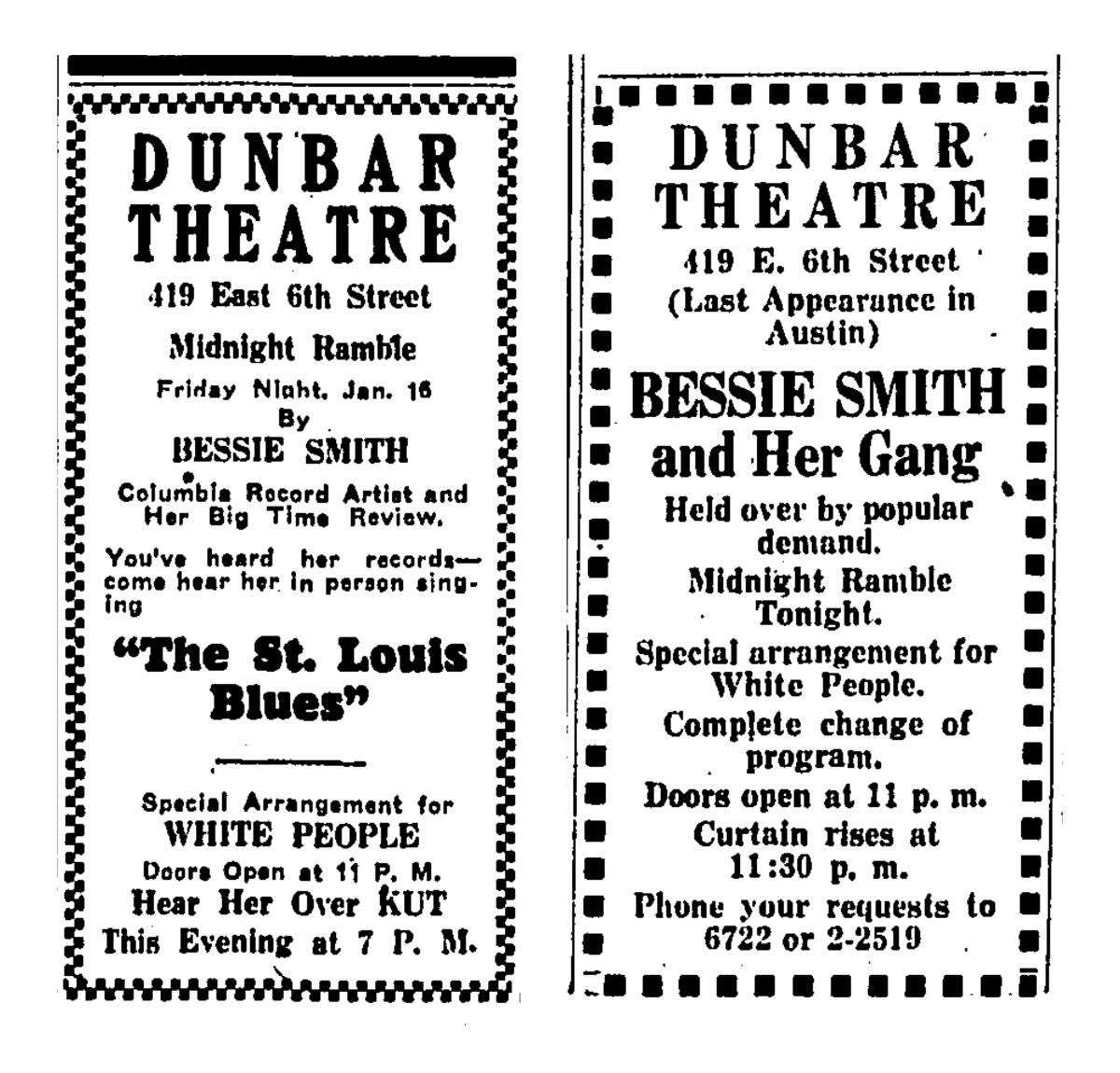

Congress Avenue was segregated, so Blacks couldn’t go to the Paramount Theatre. But they could watch movies at the Lyric Theater at 419 E. Sixth St., which was opened in the 20’s by prominent African-American dentist Everett Givens, “the Bronze Mayor of Austin,” whose dental office was upstairs. By the time Bessie Smith played there in 1931, it was called the Dunbar Theater. Blacks were also welcome at the Ritz Theater, which opened in 1929, though they had to sit in the balcony. One of Austin’s first black business owners, Ed Carrington, bought an empty lot at 518 E. Sixth Pecan St. in 1872 and built a grocery store. Brother Albert opened a blacksmith shop behind the store. You don’t even notice that historic building at Sixth and Red River on weekends because there’s so much barking human traffic.

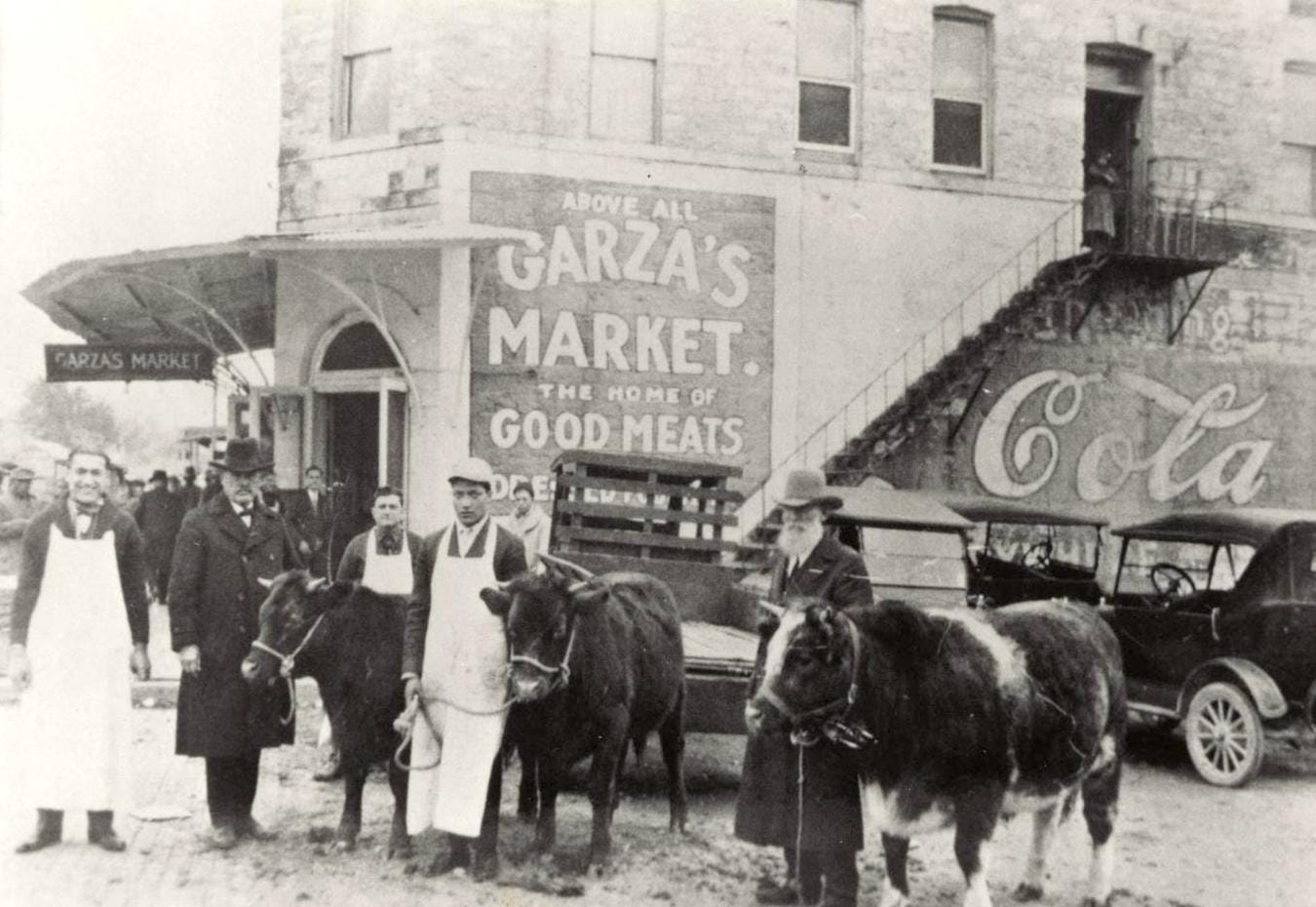

The 700 block of E. Sixth became mostly Hispanic at the turn of the 20th century, with Garza’s Meat Market and Austin’s first Tex-Mex restaurant, El Original. There were also Chinese laundries on Sixth, and Joe Lung’s Cafe, which opened in 1916 at the current location of Shawn Cirkiel’s Parkside eatery.

Austin and Sixth Street were born the same day. Mirabeau B. Lamar, who succeeded Sam Houston as president of the Republic of Texas, discovered Waterloo, as Austin was originally called, while camping near the mouth of Shoal Creek on a buffalo hunt. The town was home to two families at the time. Lamar suggested the location to the commission created to select a permanent site for the capital of Texas and they agreed, renaming Waterloo after “The Father of Texas,” Stephen F. Austin, in April 1839. Lamar’s agent, Judge Edwin Waller laid out the town in a 15-block square, naming the north-south streets after Texas rivers and the east-west streets after indigenous trees.

Sixth Street was Pecan Street until 1884, when the city had overgrown available tree names and decided to go numerical. Two years later, Sixth Street had its crown jewel when cattle baron Col. Jessie Driskill built Austin’s first grand hotel at the corner of Sixth and Brazos. (Driskill would lose his namesake hotel two years later, and die in 1890.)

For the first half of the 20th century, Sixth Street was bustling, but it started getting seedy after World War II, when Austin’s first shopping centers and suburban flight drew away customers. You could buy a reefer on any streetcorner on Sixth, claimed a 1953 Statesman article that detailed the downtown decline. When I-35 was built in 1959, erasing the prosperous East Avenue melting pot, it created a barrier from East Austin.

The almighty Driskill closed in 1969 and was saved from demolition only through a campaign that raised $2 million. The next year the Ritz became a porno movie house, as did other theaters on the strip, including the Yank Theater at 222 E. Sixth, which changed its name for obvious reasons. Transvestite streetwalkers strolled in front of the dirty peep shows, as “The Street of Dreams” had become the red light district.

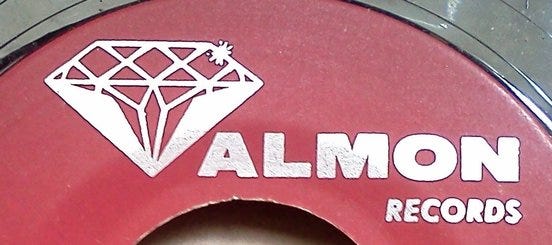

But the 300 block of E. Sixth was a hub for Spanish-language music, with La Plaza at 317 E. 6th, and the Green Spot next door pumping out accordion-driven conjunto. Austin’s first Mexican-American record label, Valmon, was at 313. In the mid- ‘50s, watchmaker Ben Moncivais leased space upstairs from the Martin Valdez furniture store and opened Valmon Jewelry (Val for Valdez and Mon for Moncivais). A big fan of Chicano soul and Mexican polka music, Moncivais began recording local acts for the mom and pop label he operated with wife Lupe. Little Joe and the Latinaires put Valmon on the map in 1963 with “Por Un Amor,” and the label with the diamond logo also had some success with 45s (recorded live to tape at the Pan-American Center on E. 3rd St.) by Roy Montelongo, Los Sonics, Alfonso Ramos, Shorty and the Corvettes and more.

The jewelry/record store relocated to South First in 1978, replaced at 313 E. Sixth by Midnight Cowboy Oriental Modeling, and continued putting out records until 1980, with about 200 releases in the catalog. Today, that upstairs space is still called Midnight Cowboy, but it’s a craft cocktail bar where a happy ending is getting the check and it’s less than $50.

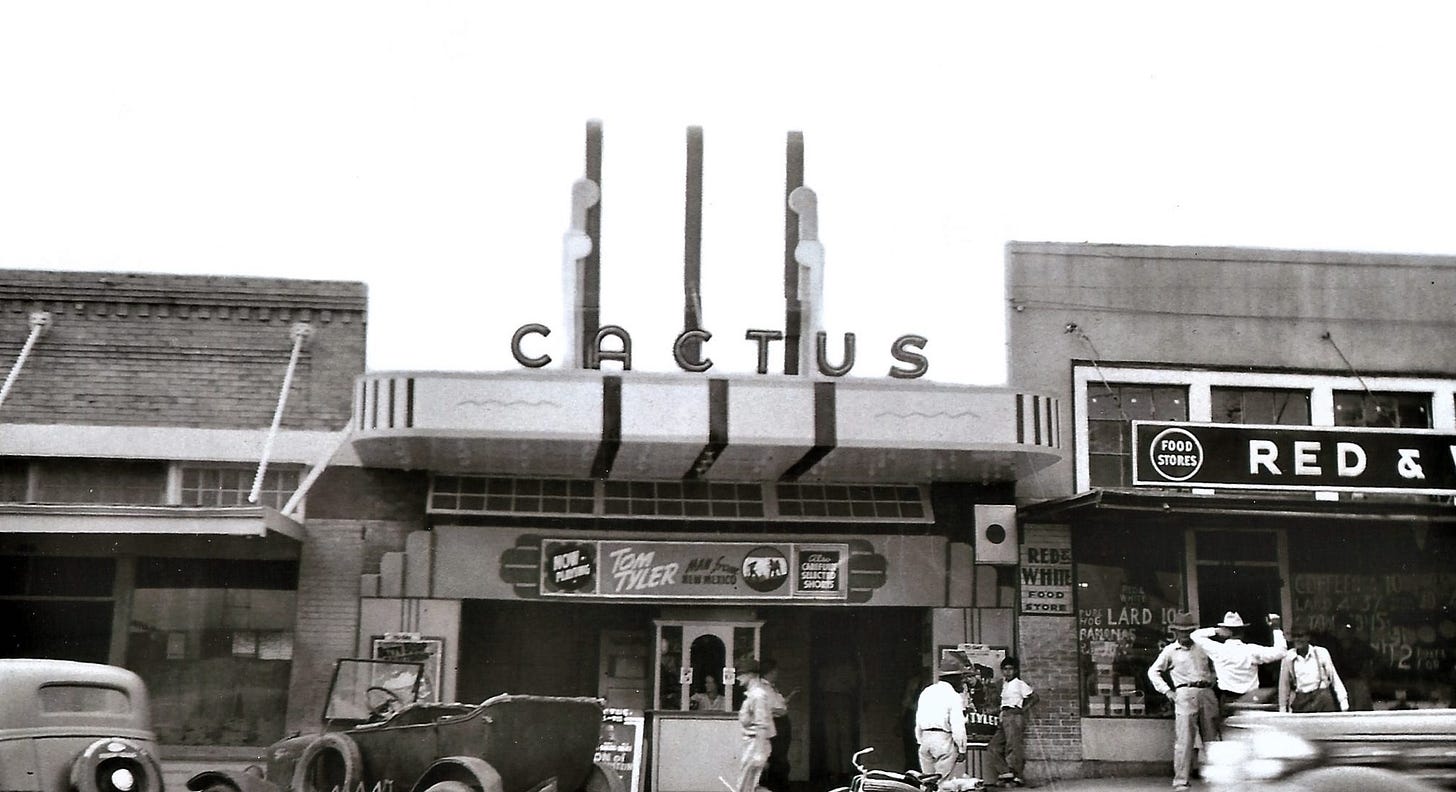

In 1974, artist Jim Franklin of Armadillo fame turned the abandoned Ritz Theater into a music venue. Shannon Sedwick and Michael Shelton kept the Ritz going for awhile, then gave Sixth an entertainment anchor with Esther’s Follies, at the former corner location of the JJJ bar (AKA the Triple Hook). Next door was where Skinny Pryor once ran the Cactus Theater, which went from Spanish-language movies to skin flicks as the Sun Theater.

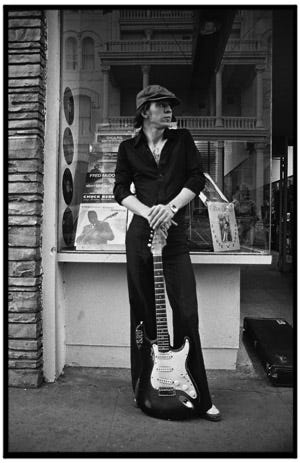

Though there’d already been blues on Sixth, with Brooks’ Home Cooking at 418 E. Sixth much more than a restaurant, and the Lamplight Saloon, where a 15-year-old Austin native Kathy Valentine (the Go-Go’s) found her first guitar hero in Jimmie Vaughan, the street had never seen anything like Antone’s, which opened at 141 E. Sixth in July 1975. That club elevated the blues scene on July 15, 1975, the night it opened.

Port Arthur native Antone was a blues fanatic who wanted to meet all those Chicago legends, so he opened a club that would treat them like royalty. Antone’s hosted the likes of Muddy Waters, Albert King, Albert Collins, Eddie Taylor and Jimmy Reed for five nights in a row, giving them a break on the road. The audiences would be filled with young musicians- Stevie Ray Vaughan, the Fabulous Thunderbirds, Lou Ann Barton, Angela Strehli, Sarah Brown, Denny Freeman, Bill Campbell, Derek O’Brien- who got to hang out with their idols after the show.

But the blues classroom was bulldozed, along with the rest of the block, in 1979 and Antone’s had to move far north, the first of five relocations through the years.

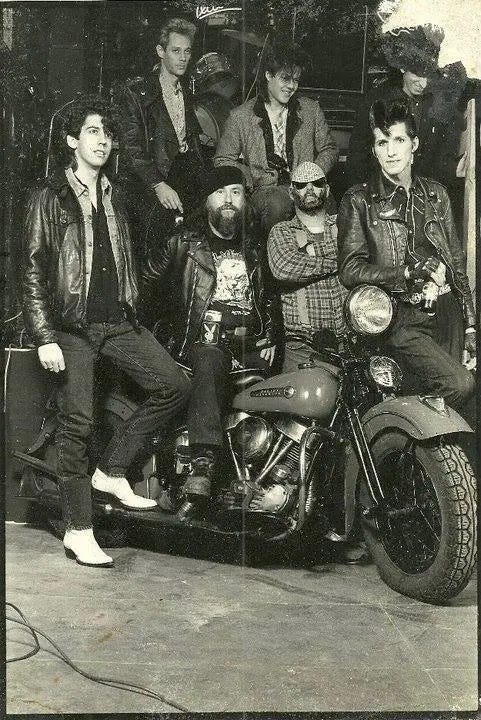

The Black Cat Lounge set a new standard for musical quirkiness on Sixth in 1985. Austin has had some remarkable clubowners, and still does, but there’s never been one like Paul Sessums, a biker who grew up in Austin, married an artist and raised their children in a raging nightclub in the heart of Sixth Street. Son Martian designed the t-shirts that everyone wore, including Timbuk 3 on The Tonight Show. Daughter Sasha ran the club in the late ‘90s, after parents Paul and Roberta retired to Palacios, on the Gulf Coast.

The thing about all these legendary Austin clubs- Armadillo, Liberty Lunch, Soap Creek- is that their calendars had a lot of filler, with maybe four or five great concerts a month. But the all-ages Black Cat was almost never dead, even if the music that night was not your thing. It was a scene.

Bands that played the Black Cat had to do 3-4 hour sets, no breaks, and for that they were paid handsomely. Paul gave them all the door, which for top acts like Soulhat, Joe Rockhead, Little Sister, Johnny Law, and Ian Moore, could be as much as $3,000 a night if they turned the house. Which isn’t hard to do when you’re playing for four hours.

The first real sensation was Two Hoots and a Holler, who packed the place every Monday night, starting around ’89. One night, leader Rick Broussard decided to take a break and Sessums was in his face. “What’s the matter, is your pussy sore?” the clubowner said and the pair had to be separated. The lucrative residency, for both club and band, was over. But that was Paul. He didn’t seem to care about money. The Black Cat was never a SXSW venue.

There was no phone and the club never advertised. There was also no air conditioning or heat, so the Sessums family would start a fire pit out back on cold winter nights. They also served free hot dogs for a few years until the health department shut that down.

The Black Cat nurtured many different scenes in its 17-year-run. It was the home of country, rockabilly, funk, jamband, blues and soul. The club was the first on Sixth to regularly book hip-hop- every Thursday night in 1990, where a short-term transplant from D.C. named Citizen Cope made his stage debut. When the B.C. burned down in 2002 it signaled the end of an era.

The first live music venue in Austin, circa 1860, was Buaas Garden, a German beerhall on the E. 400 block that was leveled in 1874 to make way for the three buildings at 401, 403 and 406 E. Sixth St. That’s why the club at 403 E. Sixth was called Steamboat 1874.

Steamboat opened in 1978 at the previous location of Billy Shakespeare’s disco, with a food first format. Owner John “Sonny” Neath also owned Steamboat Springs North at 7113 Burnet Road, an eatery which had rock music at night. The Steamboat on Sixth was a consistent positive on the scene for 21 years until it was priced off Sixth in 1999. Stevie Ray Vaughan recorded In the Beginning there, and regulars included Eric Johnson, Van Wilks, Extreme Heat and the Bizness. It was a cover band paradise where a pre-Grammy Christopher Cross sang “Sister Golden Hair” just six months before America was opening for him on a national tour. Steamboat was packed every Monday night for the Austin All-Stars jam, which musician Ernie Gammage called “the glue that held the rock scene together” for almost a decade.

In the early ‘80s they started regularly booking national acts like Los Lobos and Red Hot Chili Peppers, but the club’s glory years were in the late ‘80s/early ’90s when bar manager Danny Crooks took over booking and built a scene on local rock bands like Ugly Americans (with Bob Schneider), Del Castillo, Vallejo, Mr. Rockit Baby, Little Sister, Pushmonkey, Ian Moore, Breedlove, Sunflower and many more. It was an old-fashioned rock club, where you went to hear loud music and tried to find someone to sleep with. And you got drunk.

Crooks bought the club(house) in 1996, but had only three years before his landlady gave him 60 days to vacate. She leased the building to a nightclub group from San Antonio at a rent 2 1/2 times higher than the $3100 a month Crooks was paying.

On Steamboat's last night, Sept. 26, 1999, headliners Joe Rockhead led irate club regulars in trashing the place, spray-painting the walls, smashing mirrors and bathroom fixtures and demolishing the stage and sound booth. "I don't think Danny's going to get his deposit back," KLBJ FM's Bob Fonseca said the next morning.

"The new owners said they were going to gut the place," said Crooks, who was already home when the carnage erupted. "We just helped 'em get started."

The Black Cat was hanging on, with Flametrick Subs the top draw, but nobody on Sixth Street gets another life, let alone nine.

Clifford Antone and Paul Sessums were two maverick Austin clubowners who got their starts and made their marks on Sixth Street. And both died in their mid-50s- Sessums in a 1998 car wreck and Antone of a heart attack in 2006. Their impact on the Austin music scene is immeasurable. We didn’t have to move to New York or L.A. or Nashville because we had Antone’s and the Black Cat.

Let’s ignore how things are now, until they get better. And they will on that resilient strip. So much of our foundation as a city, as a people, is built on six blocks from Congress Avenue east to Waller Creek. Six blocks “with just enough danger to make it interesting,” as the Sun reported in ’78.

Six blocks that have represented all of Austin since 1839.

Thank you for this! I'd been looking for a run-down of the history of the music scene on 6th and this was pretty good! I'm really enjoying your articles.

I have a correction for you- The story about Driskill losing the hotel in a card game is a bit of a legend. It's repeated by sources that seem trustworthy, but it most likely falls into the category of local mythology. Even if he did lose it in a card game, it couldn't have been 10 years later since he would have been dead for 7 years by then.

I remember hearing the music from La Plaza when going to the original Antones. The area wasn't very active back then.