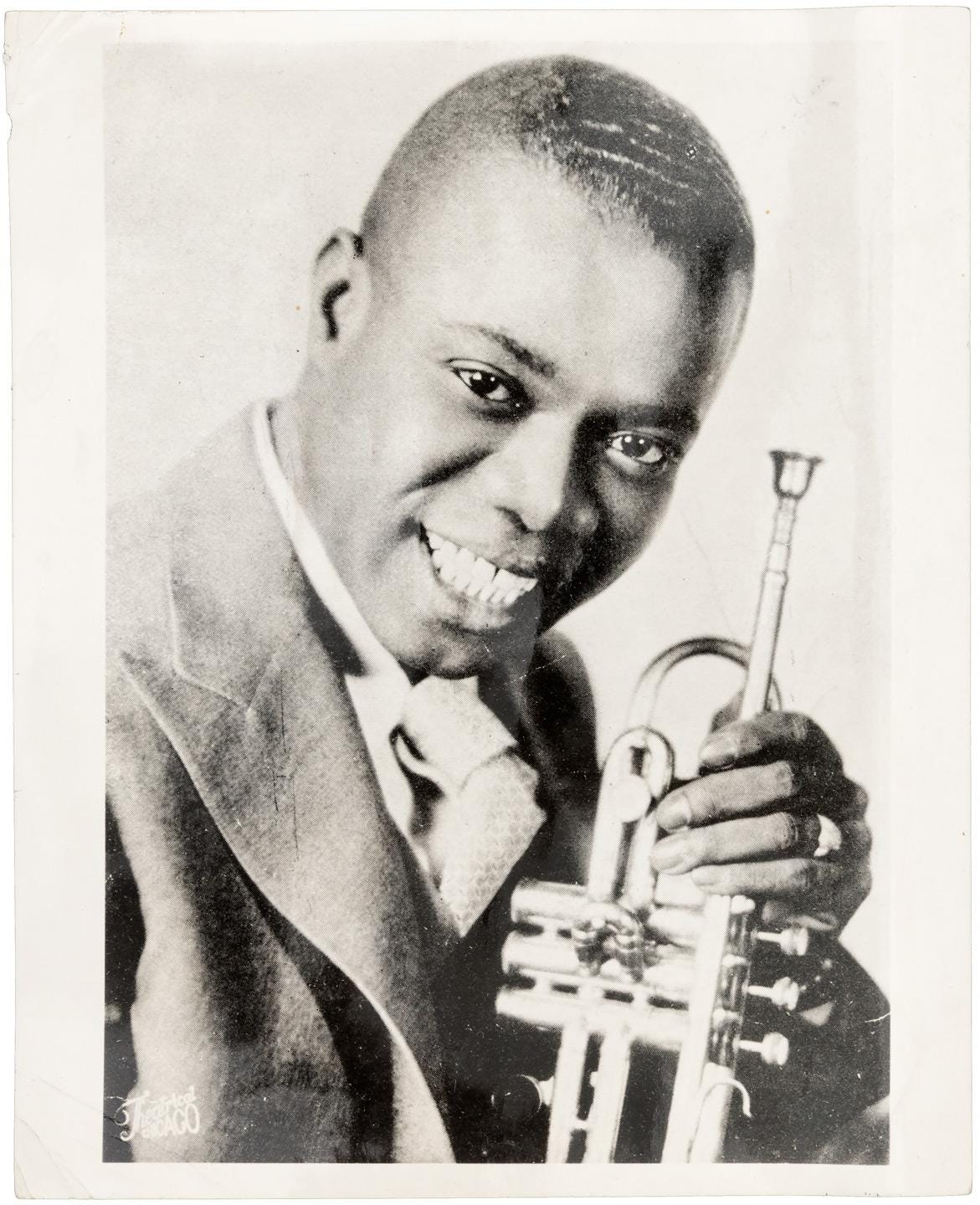

Historic Night: Louis Armstrong at the Driskill 1931

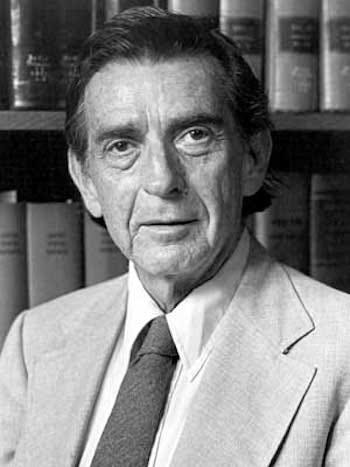

Inspired was a UT freshman who would later work with Thurgood Marshall on Brown vs. Board of Education

Charles L. Black Jr. was a freshman at the University of Texas in 1931 when he saw a placard advertising “Louis Armstrong, King of the Trumpet, and His Orchestra” at the Driskill Hotel. He didn’t know jazz from jehovah, but he bought a ticket. There would be girls and dancing, which was worth 75 cents admission.

Six bits changed his life. “It is impossible to overstate the significance of a sixteen-year-old Southern boy’s seeing genius, for the first time, in a black,” he wrote in 1979. “We literally never saw a black man, then, in any but a servant’s capacity.” Black’s essay “My World with Louis Armstrong” was published in the Yale Review and quoted in Ken Burns’ 10-hour JAZZdocumentary.

The Austin High graduate went on to become a noted Civil Rights attorney, who taught constitutional law at Columbia and then Yale for a combined 40-plus years. In 1954, he helped Thurgood Marshall draft the brief for the Supreme Court case known as Brown vs. Board of Education, a victory which declared school segregation unlawful, and galvanized the movement to end the racist white regime in the South.

Armstrong, perhaps the greatest musician America has ever produced, was forbidden to stay at the Driskill during his appearances Oct. 12-14, 1931. The hotel did not allow Black guests until quietly desegregating in 1962, two years before the Civil Rights Act was signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson.

Armstrong’s hold never left Charles Black, who died in 2001 at age 86. “All through those years, he was letting flow, from that inner space of music, things that had never before existed,” the professor wrote 48 years after that show on Sixth Street. When they say the Driskill is haunted, they’re right.

Satchmo had played Austin earlier in 1931 at the Cotton Club at 817 E. 11th St. (formerly Royal Auditorium). After hearing the hometown opening act, the Dixie Musicmakers, Armstrong asked Israel Fontaine, the band’s trumpet player, if he wanted to join his touring band. “Of course I said yes,” Fontaine said in 2001, when I visited him, aged 91, at his home in East Austin. “I knew there was a lot I could learn from him. I’d never heard anyone play the horn like that before.”

Austin High senior Tommy Hill remembered standing behind a rope at the Cotton Club with the handful of other white kids, amazed at the powerful performance. “He played 20 choruses of ‘Tiger Rag,’ ” recalled the 87-year-old in 2001. “He was sweatin’ like crazy, with a white towel across his back, but he just kept playing.” A local radio station broadcast Armstrong’s Cotton Club performances, and the bandleader sent a message to his mother in New Orleans even though the airwaves didn’t go any farther than the Austin area.

“There was a small club in East Austin called the Blue Knight, and they took up a collection to try to get Louis Armstrong to play,” recalled Fontaine, who did only one short tour and didn’t play the Driskill shows. “They wrote him a letter that said they could pay him $100, and he wrote back and said he’d play for $100, but they’d have to come up with a lot more money to also get the band.”

The grandson of former slave Jacob Fontaine, who published the first issue of the Gold Dollar at 2402 San Gabriel St. in 1876, Israel also went into the printing business. He gave up jazz in 1943 when he joined the ministry at the Mount Zion Baptist Church founded by his grandfather. “Preaching and publishing- that’s in my blood,” he said. Just as his father George put out the Silver Messenger, Israel started an African-American newspaper in 1938 called the Austin Express.

The 1500-capacity Cotton Club, which booked many of the hot swing bands, like Cab Calloway and Jimmy Lunceford, remained open off-and-on until 1944, when the two-story building was repurposed as a dormitory and dining hall for Samuel Huston College across the street. The “unique hepcat haven where all the dark and light folk meet” (Daily Texan1942) was torn down in the ‘50s, when East Avenue was broadened into I-35, and became a parking lot

Louis Armstrong wasn’t the only African-American icon to play Sixth Street, the most integrated six blocks in Austin, in 1931. The legendary blues singer Bessie Smith sang for two nights in January at the Dunbar Theater (419 E. Sixth St.), owned by dentist Everett Givens, “the Bronze Mayor of Austin.” Givens had opened the Lyric Theater there in the early ‘20s as a movie house for Blacks. But when the far bigger Ritz Theater opened in 1929, he lost a lot of business, even though Blacks had to sit in the balcony. It lasted only about a year or two as the Dunbar.

Outstanding. You tracked stuff down that I searched for, for years.

As usual, more fascinating facts from you on the hep cat scene in Austin! Love this stuff! Just saying. Ketch