I.M. Terrell Panther Band: Separate but Superior

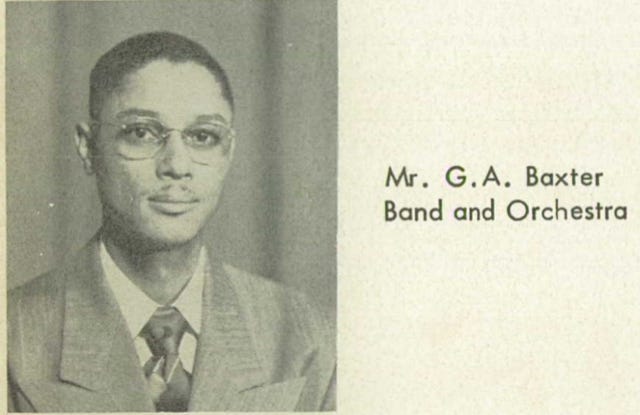

Gilbert A. Baxter taught several greats of jazz and R&B, including Ornette Coleman, King Curtis, Dewey Redman, and Ronald Shannon Jackson

In 1958, music changed forever when Ornette Coleman pioneered the “free jazz” movement with his debut album Something Else, and King Curtis made the squealing, honking tenor sax the new lead instrument of rock n’ roll with “Yakety Yak” by the Coasters.

Their proteges Ronald Shannon Jackson and Cornell Dupree would go on to define jazz/rock fusion drumming and tasteful session guitar, respectively.

Four quite different musical styles, yet they sprung from the same all-black I. M. Terrell High School band room in Fort Worth. Under the stern and steady direction of G.A. Baxter, the Terrell High Panther Band also gave the music world sax greats Dewey Redman and Julius Hemphill, noted clarinetists John Carter and Prince Lasha, and drummer Charles Moffett, who also became a revered educator. These are names known to fans of adventurous jazz, and yet they graduated from a music program that didn’t allow improvisation.

“Mr. Baxter could play every instrument in the band,” said James Mallard, 85, who graduated from Terrell in 1954 and fronted a Fort Worth R&B band for decades. “He’d come over and show you what to play and how to play it.” With Adlee Trezevant teaching music theory, the Terrell players epitomized the school’s unofficial motto during that time of segregation: “separate but superior.”

Music was seen as passage to high culture, so the popular and somewhat sinful styles of jazz, swing and blues were forbidden on Baxter’s bandstand. Instead, he drilled fundamentals into the student musicians he led from 1946-1961. During football season the band, a mix of males and females in gold and blue uniforms, would play John Phillips Sousa marches, while the rest of the school year was devoted to classical music. A slight, bespectacled man, with a thin mustache, Baxter ruled his band with an iron baton.

Alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman, who received a Lifetime Achievement Grammy in 2007 for an illustrious career as a musical innovator, was one Panther who bucked the bandleader’s regimentation. A member of Baxter’s first band at Terrell, Coleman (Class of ’49) liked to pepper Sousa marches with sax riffs of his own invention. The loudness of the band usually masked the mischief, but one day during “The Washington Post March,” Baxter distinctly heard a sax that was not following the arrangement and sent Coleman to the principal’s office.

“All of us who were into jazz probably got put out a few times,” Coleman’s cousin James Jordan, also a sax player at Terrell, told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram in 2003. “Coleman, more.”

It’s not known if the world class iconoclast Coleman was let back into the orchestra, but his musical education was furthered, nonetheless, in Fort Worth clubs where his Jam Jivers made money playing rhythm and blues, jazz or “Stardust,” depending on the audience. Their hometown hero was bebop sax player Red Connors, Fort Worth’s answer to Charlie Parker.

In his later years at Terrell, Baxter eased up on his “no jazz” edict, recalled drummer “Ronnie” Jackson, as he was known in Fort Worth. During lunch hour, Baxter would open the band room for whoever wanted to jam and then lock them inside. “We had access to all the instruments,” said Jackson (Class of ’58), the only drummer to play with all of the three main pioneers of avant-garde jazz: Coleman, Albert Ayler and Cecil Taylor. “We didn’t go to lunch.” In a 1981 interview in Musician magazine, Jackson spoke of Baxter’s dedication. “He loved to perfect a band. He put his whole life into music, to the point it would drive him mad.”

Though Terrell opened in 1882 as East Ninth Street Colored School, and closed in 1973 during the desegregation of schools, the only nationally prominent musicians came out of Baxter’s fifteen-years as band director. Divorced from schoolteacher wife Lillian in 1959, Baxter left Terrell (named after first principal Isaiah Milligan Terrell) at age 44 for unspecified health reasons. “We heard he’d had a nervous breakdown,” said former Terrell student Bob Ray Sanders. Baxter remarried in Dallas three years later. Then, the legend became a ghost.

In a 1984 Fort Worth Star-Telegram article about Terrell’s amazing musical legacy, the band director was referred to as “the late G.A. Baxter.” But Gilbert Abraham Baxter lived until 2005, when he died at age 88 in his native Oklahoma City. There was no obituary in the paper, just a death notice for the teacher whose students changed music. He was survived by Doris, his wife of 41 years.

Baxter was still at Terrell when Coleman blew minds with a trio of albums- The Shape of Jazz to Come (1959), Change of the Century (1960) and Free Jazz (1961)- that befuddled as much as enlightened. The saxophonist split listeners into “genius or grifter?” camps, as he abandoned the traditional notions of melody and chord progressions, encouraging his musicians to play what they felt, in the true spirit of improvisation. The complex blend Colemen called “harmolodics” and sometimes played on a plastic sax, was as far from John Phillip Sousa as music could get.

Coleman’s chair in the Panther Band’s saxophone section was taken by former equipment manager Curtis Ousley (Class of ’52), who would become famous as King Curtis. The sax on Aretha Franklin’s “Respect” is perhaps the King’s best-known solo, but if you heard hot tenor sax on Top 40 radio in the ‘60s, you were most likely listening to King Curtis.

Curtis also began his career as a jazz player, ignoring music school scholarships to hit the road with Lionel Hampton’s band- a path previous taken by the original “Texas Tenors” Herschel Evans of Temple, Clifford Scott of San Antonio and Houstonians Illinois Jacquet and Arnett Cobb. Sax players from the Lone Star State favored a rhythmically- driven, heavily-articulated sound of squeals and honks. Dewey Redman (Class of ’48) brought that aesthetic to free jazz, most famously in Coleman’s band of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Son Joshua Redman continues the tradition.

“King Curtis was my main man,” Bobby Keys of Slaton, near Lubbock, told me in 2012. Keys continued the “Texas Tenor” tradition with the Rolling Stones until he passed away in 2014.

Though Curtis released hit instrumentals such as “Soul Twist” and “Memphis Soul Stew” under his own name, he made most his money as a studio musician and arranger for Atlantic Records. Besides his smash hits with the Coasters, King’s sax became a second voice on “A Lover’s Question” by Clyde McPhatter, “I Cried a Tear” by Lavern Baker and those classic Aretha Franklin albums. Producer Jerry Wexler used to have three sax players on each session until he realized that Curtis alone could cover the parts.

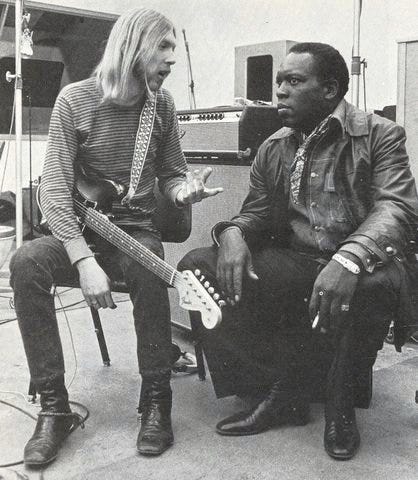

Back in Fort Worth for a funeral in 1961, Curtis sat in afterward with an R&B band, the Red Hearts, whose guitarist had great touch. Cornell Dupree had played sax in the Terrell band until he heard Johnny “Guitar” Watson his sophomore year and dropped out to play electric guitar full-time.

A few weeks after the jam with Curtis, Dupree was the newest member of the Kingpins, living in Manhattan with his new boss. Besides going on tours with Aretha, Sam Cooke and the Beatles (opening the 1965 Shea Stadium show), Dupree earned the “Mr. 2,500” nickname because, in his estimation, that’s how many sessions he played on. “Rainy Night in Georgia” by Brook Benton is a prime example of the mood-setting skill of Dupree’s guitar. He also shined on several Paul Simon solo records.

King Curtis was senselessly stabbed to death in 1971, at age 37, but his influence on Dupree lived on. “He taught me how to pay attention, how to listen… less is more,” Dupree recounted in a 1997 Dallas Observer article. “Speak when you have something to say, otherwise stay in the background and don’t interfere. Coming through his band, I look at it as my degree.”

Good students become good teachers, but sometimes the bad ones do, too. The musical disobedience Ornette Coleman displayed at Terrell evolved, brilliantly. In its 2015 Coleman obituary, the New York Times credited him with “personifying the American independent will as much as any artist of the last century.”

After Terrell, Ronald Shannon Jackson went to college to study music, but “they’d been teaching me out of the same books as in high school and I’d been playing the same Sousa and Wagner,” he told Musician. “The teachers couldn’t teach me nothing new.” After a year at Lincoln University in Missouri, the drummer set off for New York City where he received a true musical education at “Coleman University,” as he summed up his time in Ornette’s Prime Time band.

“Knowledge is useless unless you share it,” was one of his mentor’s favorite sayings.

Like abstract expressionists who started off by painting in a traditional, realistic style, the legendary musicians who came out of the Terrell High Panther Band learned the basics of rhythm, melody, harmony and chords before they went on to splash and drip their new sounds over the American musical landscape.