INFESTED: Promoters Reap the Groove Fields

From T-Bird Riverfest to ACL Fest, Austin takes it outside

Austin has hosted multi-act, multi-day outdoor events since 1964 when Rod Kennedy presented the KHFI Summer Music Festival at Zilker Park’s Hillside Theater. That lineup over six days in July included the return of folk singer Carolyn Hester, country bluesmen Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb, plus jazz combos, Western swing, and a symphony orchestra. Admission was free.

The first big ticketed outdoor affair was 1966’s Longhorn Jazz Festival at Disch Field (next to City Coliseum), with a jaw-dropping lineup including Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Coleman Hawkins, Dave Brubeck, Stan Getz, Gerry Mulligan and returning Austinites Teddy Wilson and Kenny Dorham. Kennedy co-promoted that one with Newport impresario George Wein.

We’ve had our Aquafests and our Sunday Breaks and Willie’s Picnics and Hill on the Moon, but Austin didn’t really get fest-crazy until the 2000s, with the Austin City Limits Music Festival leading the way in Sept. 2002.

The edgier Fun Fun Fun Fest, produced by Graham Williams and Transmission Entertainment, and Rich Garza’s Latin-themed Pachanga Fest, came to Waterloo Park in 2007 and 2008, respectively, though Pachanga moved to Fiesta Gardens the next year and Fun x 3 to Auditorium Shores. Austin Psyche Fest, curated by Black Angels, debuted in 2008, eventually changing its name to Levitation, but it didn’t move outdoors until 2013 at Carson Creek Ranch.

Then there was the bluegrass-heavy Old Settler’s Music Fest, which started in the ‘90s at the park of that name in Round Rock, had 15 glorious years at the Salt Lick Pavillion, then bought its own fenced-in boonies near Lockhart in 2018. OSMF announced last month that they’re skipping 2024 and planning to sell their vast acreage.

ACL’S TIME HAD COME

ACL Fest grew out of the victory celebration concert following Lance Armstrong’s first Tour de France title in 1999. Armstrong’s manager Bill Stapleton, a former Olympic swimmer, hired Middleman Productions, which was basically Charlie Jones and Lisa Schickel, to put together a big concert on Auditorium Shores with a week’s notice, and it was just one of those magical nights where everything went right. Then, Middleman confidently handled the city’s massive Y2K celebration and the world didn’t end, so Stapleton brought Jones aboard to head a new live events division of Capital Sports & Entertainment. Charles Attal of Stubb’s was brought in to book talent.

Affiliation with Lance gave CSE all-access to starstruck Austin, so Zilker Park was made available to a new yearly festival based on the New Orleans Jazzfest model. The City Parks Department had turned down all other promoters after an MTV sports and music fest (snowboarding, Wu Tang Clan) in 1997 left the park looking like the site of a tank battle. But naming this new festival after civic pride point Austin City Limits carried a lot of good will. Even the joyless neighborhood associations signed off on this one.

The announcement was made at a press conference at Zilker on April 30, 2002, five months from the festival kickoff, which didn’t give Attal a lot of time. Festivals are usually booked a year in advance. “I called in every favor I had,” said Attal, who made a lot of contacts booking the 2100-capacity Stubb’s Waller Creek Amphitheater since it opened in 1996.

The first act to confirm at ACL was Colorado jamband String Cheese Incident, who’d just played to about 20,000 fans over three nights at Waterloo Park. Next was Pat Green, who had a similar draw, and the same lack of respect from music snobs. Then came acts who’d played the TV show: Emmylou Harris, Los Lobos, Nickel Creek, Wilco, Ryan Adams, Blind Boys of Alabama, Gillian Welch. Playing the final slot of the two-day event was the Arc Angels, who reunited for superfan Armstrong. They were the last Austin band to headline.

The 70-act lineup wasn’t firm until three weeks before the Sept. 29-30 event, which caused a lot of anxiety within the fledgling CSE. The break-even point was 30,000 fans a day at $25 a head, but when an initial allotment of wristbands went on sale for $20 each, just two months before the festival, they sold only 700. A midnight call from France, where Armstrong was in the midst of his fourth consecutive Tour win, had a semi-panicked Stapleton wondering if CSE should hedge its bet by announcing only half the lineup, then cutting back the other half if the tickets tanked. They stood to lose a million dollars. “It was gut-check time,” Stapleton told me in 2003. “We all knew it was a great idea whose time had come and it came down to this: Do we want to be the company that plays it safe, or do we want to follow our convictions full speed ahead?”

When the Star Wars theme came out of the speakers big and loud as the gates opened, it was the sound of success, a tradition for years to come. The maiden ACL Fest drew 42,000 people on Saturday and about 35,000 on Sunday. Walkups snaked in lines 500 yards long, but as soon as everyone got in, all that frustration disappeared, like arriving home to your sweetie after a horrible flight.

There would be much bigger lineups (and crowds) in the next 20 years of ACL Fest, but in terms of sheer joy, that first year will never be topped. Everybody was just so goddamned happy to be out at the park on a perfect day, listening to good music and eating food a big step up from turkey legs and funnel cakes. Even security was in a good mood.

The skyline of the city sparkled in the background like possibility. It looked quite different than the one we see today, but the view has always been glorious from Zilker Park.

Every year there’s a call from cranky Austinites to move ACL out of our downtown jewel, especially when a second weekend was added (with an identical lineup) in 2013. Move it to the F1 track! They don’t get that the thing that makes ACL Fest special is that it’s right in the middle of town. What a way to show off Austin, and to make two million dollars a year for the Parks Department. It’s a model that C3 used to revive the rotting carcass of Lollapalooza at Chicago’s Grant Park in 2005.

CHARLIE COMPANY

CSE became C3 Presents in 2007 when Charlie Walker left his job as president of Live Nation’s North America division to become the 3rd C. You don’t see guys leave a top job in L.A. for a medium market, but “I’m just an Austin kind of guy,” Walker said. They became the “Three Charlies,” as they were known in the industry,

Seven years later Walker’s old company bought 51% of C3 for about $125 million, and the three Charlies were rich. And they kept their jobs.

Sharing a 600-sf office on W. Fifth St. in the late ‘90s, Charlie Jones and Charles Attal started out as nobodies on the Austin music scene. But they were willing to do whatever it took to find their place, and now they’re flying private, though Jones went off in his own direction in 2019.

Moving to Austin after high school in College Station, Jones became involved with the music business because he was infatuated with Little Sister, a funk jam band featuring Patrice Pike. He went from volunteer roadie to manager in record time. Jones produced his first big outdoor shows in conjunction with KLBJ or KGSR so he could get Little Sister on the undercard in front of thousands.

A budding auctioneer from an antique family, Attal became the booker at Stubb’s because he was in a band (the forgettable Clown Meat), so the other four partners figured he knew about music. Outdoor concerts were going to be just an occasional sideline to the barbecue of legendary Lubbock pitmaster C.B. Stubblefield (who sadly passed away a year before the launch of what eventually became a $100 million BBQ sauce company). But the Fugees changed all that. They were the hottest group in hip-hop when they played a SXSW showcase at Stubb’s in 1996- months before the joint was officially open. But they had to leave the uncovered stage when rain came pouring down midway through the second song. As word circulated that the show was over, singer Lauryn Hill came face-to-face with Attal. “But we want to play!” The greenhorn promoter did everything he could to see that it happened, and after about an hour delay, the Fugees came back onstage and rewarded those who’d stuck around with a show they’ll never forget. Attal had been baptized. Stubb’s would become known more for music than smoked meat.

But Jones and Attal still had traces of green when they put themselves in the big league of promoters. Before they landed on “Austin City Limits” as their festival name, Jones and Stapleton approached Jimmie Vaughan to see if he would license “The Stevie Ray Vaughan Music Festival” as the name of their event. Jimmie said “no” between the two syllables of “Music.” Which actually turned out to be a good thing for CSE. Could you imagine Iggy Azalea doing her Nicki Minaj impression at the SRV Fest?

T-BIRD RIVERFEST

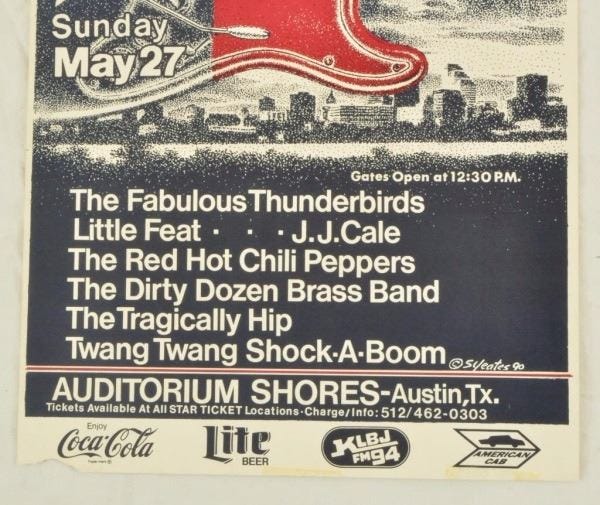

CSE was thinking back to the ‘80s, when the biggest outdoor music event in Austin was T-Bird Riverfest, attracting about 15,000 to Auditorium Shores on a Saturday in June. Produced by French Smith from ‘83- ‘91 and booked by the headlining Fabulous Thunderbirds through manager Mark Proct, the Riverfest had stellar line-ups, seemingly picking five names out of a hat containing Bonnie Raitt, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Carlos Santana, Los Lobos, Little Feat, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Nick Lowe, Dwight Yoakam, Robert Cray, Dave Edmunds, and Delbert McClinton. The T-Birds headlined, and opening the show was whoever Stevie’s Irish publicist Charles Comer maneuvered onto the bill.

Comer had first come to the States as tour publicist for the Beatles and carried himself as the legend he was. And since he controlled backstage access at Aud Shores, he wielded great power in the Austin media. Payola was nothing compared to “passola” in courting influence.

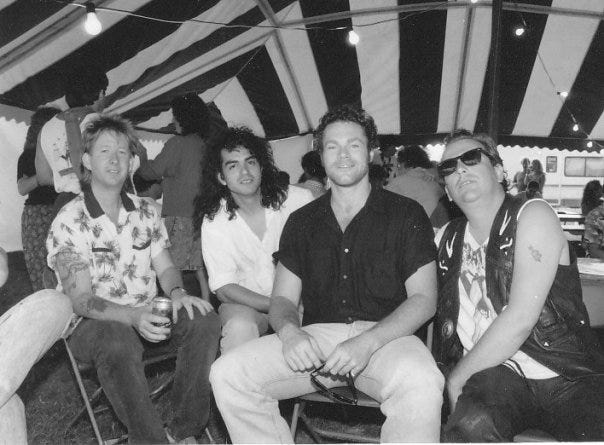

Even more than a full day of music, the T-Bird Riverfest showed you where you stood in the music scene pecking order. If you bought a ticket and spent all day in the crowd, you were just another townie. Backstage was where the action was. C-Boy Parks cooking barbecue, unlimited kegs of beer, every top band in town hanging out with “celebrities” like Margot Kidder and David Keith. This where I had the revelation that heaven is probably just backstage at hell.

Now, the best pass was a laminate that said “STAGE.” You could go right up and stand next to the Hammond organ if you wanted. I only got that ultimate access once at Riverfest, and it almost ended my life. It was 1990, the year the lukewarm Chili Peppers got Red Hot with Mother’s Milk. Besides the T-Birds, also on the bill were Little Feat, J.J. Cale and the Tragically Hip. But the crowd was totally geared up for the shirtless Peppers. As soon as they came out, thousands of people rushed the stage, hitting the railing with such force that the stage lurched back a few feet. It felt like it would tumble into Town Lake. The band stopped mid-song until security could get those people to take a step back. Meanwhile, I got the hell down those stairs! I wasn’t going to risk my life for “Party on Your Pussy.”

Charles Comer was one of the people fellow Irish music man Chesley Millikin spoke with almost daily until his passing. Chesley, SRV’s first manager and the one who opened all doors, kept up on music biz and consulted with Charles, Sam Cutler, and another NYC music publicist (“Imelda”) regularly and told close friends great bits of their phone calls. The old personalities were more interesting than the current crop of all-corporate, politically correct types of today.

One year it started raining hard during the T Birds set and the big tarp over the top was sagging from all the water like it was about to break. The T Birds decided to pause their show while all of us "townies" were getting drenched. So in line with their latest hit everyone started yelling "Aren't you tough enough" or something like that? Anyways still fun even without the music.