The '20s: Jazz Age comes to UT

Gardner and Corley families had Austin roarin', then helped stave off depression in the '30s

The 1920’s Austin music scene revolved around the University of Texas- as it would for decades- so if you wanted to make a living as a musician you played frat dances, which back then were called “Germans” because the first ones were organized in the early 1900s by the German Club. This handpicked inter-fraternity supergroup of popular kids hosted Saturday night dances at the Knights of Columbus Hall at Eighth and Colorado Streets. Claiming that 600-capacity venue could barely handle their members, pledges and dates, the Germans denied admission to “barbs” -for Barbarians- students socially independent of fraternities and sororities.

Such snobbery didn’t sit well with the Board of Regents, which voted to dissolve the German Club in 1929, along with other exclusive “ribbon clubs” on campus like the Skull and Bones. Even after student dances were officially labeled All-University, they were called Germans until the ascent of Adolph Hitler in the late ‘30s.

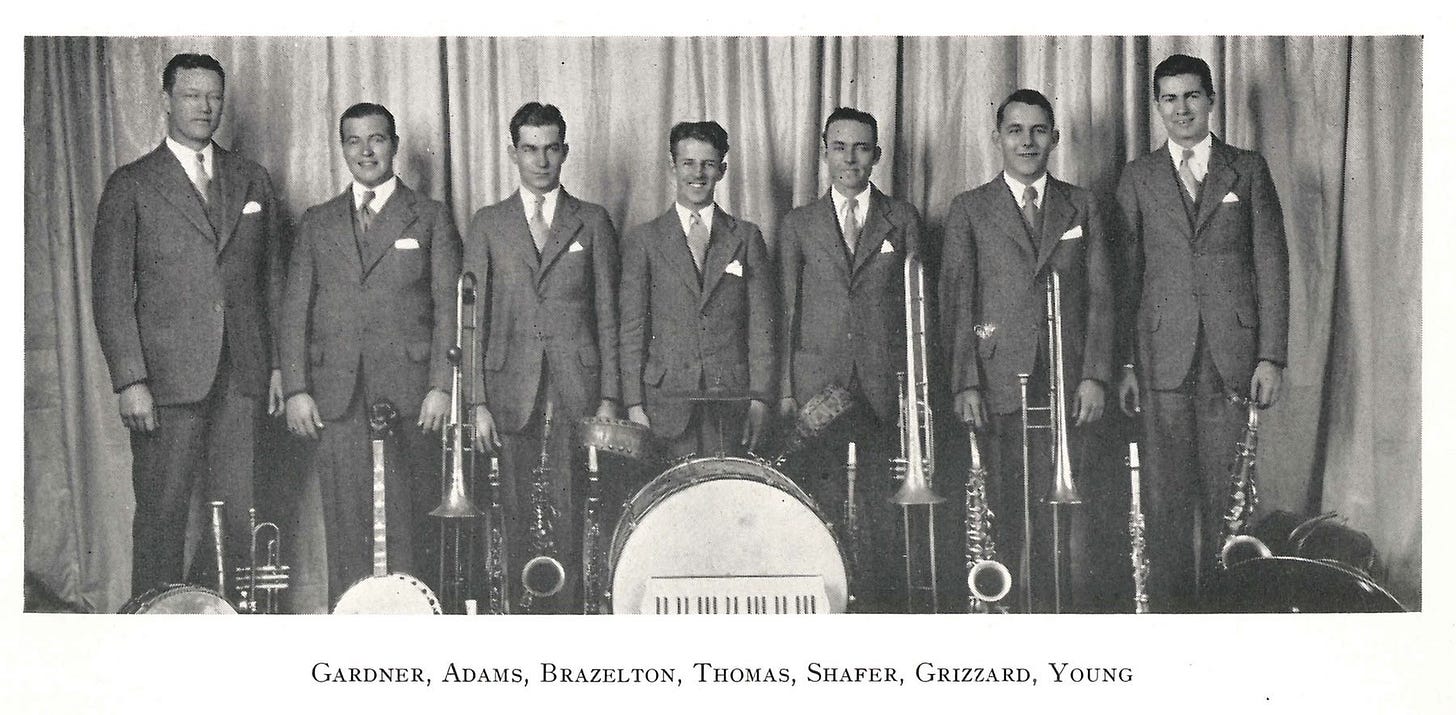

One of the first popular jazz orchestras to play the Germans was the Howell and Gardner Band-its of 1919, led by Jay and Hilton Howell of Cameron, and Steve Gardner, who also played sax for the Longhorn Band. Originally from Colorado City, in West Texas, Gardner moved to Austin with his musical family when he was a teenager. Enlisting in the Army in 1917, he led the band at Camp Mabry, then attended UT after the end of WWI.

Steve Gardner put together his own orchestra in 1923, with brothers Fred on sax, John on tuba and Derry on banjo. That same year, banjo-playing sister Bernice Gardner joined the Texette Sextette, an all-female jazz band from the Scottish Rite dorm.

For a city of less than 50,000, Austin had a vibrant music scene in the ‘20s, but the Stock Market Crash of ‘29 led to the Great Depression, for country as well as music scene. Gardner economized his 12-piece orchestra to a combo- Steve Gardner and His Hokum Kings- and just plowed through the doldrums. The band had two Tommy Howells, who switched off between piano, trumpet and clarinet, so they called the one with darker hair “Black Tommy.” Also a multi-instrumentalist, Gardner eventually settled into the string bass role. This information comes from a 1965 Statesman interview of oldest brother J. Harris Gardner, who left the family band early to start a distinguished career on the bench. Travis County’s first juvenile judge, he was the namesake of Gardner House detention facility (now Gardner-Betts). When their father died in 1913, Harris helped raise his younger siblings. He always strived positive parenting as the key to eradicating delinquency. Judge Gardner passed away in 1978 at age 86.

While Steve Gardner’s bands (one called “Steve’s Stevedores”) battled Gertrude Shoch’s Varsity Peacocks and Jimmie’s Joys, led by Jimmie Maloney (whose gimmick was playing two clarinets simultaneously), for lucrative German gigs, the Texettes played “gym-jams” for barbs most Friday nights. With a repertoire of popular songs like “Carolina in the Morning” and Sophie Tucker’s “You Gotta See Mama Every Night,” the Sextette played live on the Statesmen’s radio station WNAS to promote those shows at UT’s women’s gymnasium. The group also played between movies at the Queen Theater, at the 1923 opening of the pavilion at Barton Springs, and at fundraisers for the Memorial Stadium construction. Nobody’d ever seen an all-female jazz group before, so the Texettes usually got wild ovations, “forced to encore every selection they played,” according to one review.

Led by Miss Clyde Watkins on violin and featuring drummer Etelka “Tech” Schmidt, Bernice Gardner on banjo, Jane Worthington on piano, and the sax duo of Bernice Milburn and Maizine Grady, the Texettes formed the same year as California’s Helen Lewis and Her All-Girl Jazz Syncopators, who are often credited as the first all-female band. That was almost 15 years before the legendary International Sweethearts of Rhythm.

The Texettes were active only two years, with no known recordings, but they own a piece of history.

One of Steve Gardner’s greatest achievements was directing four orchestras as one mass group at the Majestic Theater (now the Paramount) in 1925, and the next three Novembers. He went on to head UT’s band and orchestra department, while keeping a steady schedule of night gigs. But one job he’d probably liked to have turned down was playing the debut concert at the Ku Klux Klan hall at E. Fifth and San Jacinto Streets in 1924. Still in the bask of 1915’s Klan-glorifying blockbuster Birth of a Nation, the white-robed bigots did not have the despicable reputation in ‘24 they would have just a few years later. The Klan posed as a Christian organization out to make America great again, and in February ‘24, they put on a circus attended by thousands. Their giant burning cross at the entrance, just south of the Congress Avenue Bridge, could be seen from miles away.

In the late ‘20s, younger brothers Fred and John Gardner (who called Steve “Himself”) broke off to form their own territorial band Fred Gardner and the Troubadours, recording four songs in San Antonio for OKeh Records in 1930. They often battled Steve’s Hokum Kings at the Texas Union, which opened in 1933, or the rooftop ballroom of the Stephen F. Austin Hotel. But the Troubadours lasted only a few years, while Steve’s band, whose ever-evolving bandstand included notable pianist Red Camp and saxophonist Ben Young for a time, was king until finally disbanding in 1941. Steve Gardner went to work for the state department, and passed away in 1950.

In the late ‘20s to mid- ‘30s, one of the most popular dance bands in town was George Corley and His Royal Aces, a nine-piece “colored orchestra” from Sam Huston College in East Austin, which included brothers Reginald, John and Wilford Corley. The Aces played swanky gigs for fraternity parties, at the Avalon Dinner Club on far North Lamar, and at the Driskill and other hotels. After the Avalon closed in late ‘38 amid noise complaints from neighbors, Corley’s group moved to the Rocky River Tavern on Burnet Highway. The Aces’ homebase on the Eastside was the Paradise Inn at 813 E. 11th St. They also played before baseball games at Riverside Park circa 1934, and at the East Avenue Park which was where I-35 and E. 11th is now.

When John Corley took over leadership after WWII, the Royal Aces played La Conga and the Trocadero on South Congress, which was then called the San Antonio Highway.

The Corley name was well-known around Austin from “the Ol’ Lamplighter,” George M. Corley Sr. (born 1878), who serviced as many as 900 gas lamps- trimming wicks and relighting pilots- for decades before electricity was no longer a luxury. In a 1961 Statesman profile, before he died that year at age 83, Corley Sr. talked about once replacing about 100 mantles in a day after a cricket infestation.

He also touched on dreams of being a musician before he found his trade, and started his family. George Sr. had a trumpet, but didn’t have time to practice, so he passed it on to George Jr. and encouraged his other five kids to pursue music, which they all did. George Jr. and Reginald became music teachers at Black high schools in Oakland and D.C. respectively. Not sure what became of the other Corley’s. If anyone knows, please contact me at yikescrawford@gmail.com. And if you have a photo, lunch is on me.

Michael Schmitt’s Austin music history web site local-memory.org was a good source for this story, and worth exploring.

Thanks for reminding many of the great unwashed just how widespread and popular the KKK was in the 1920s. Most people have no idea that it was once considered "respectable" to be a member of a hate group. Keep shining the light on this. (And FYI: Blacks were not allowed to enter the State Fair of Texas except on "Negro Achievement Day, the one day they could attend. This sorry practice lasted until well into the 1960s.)