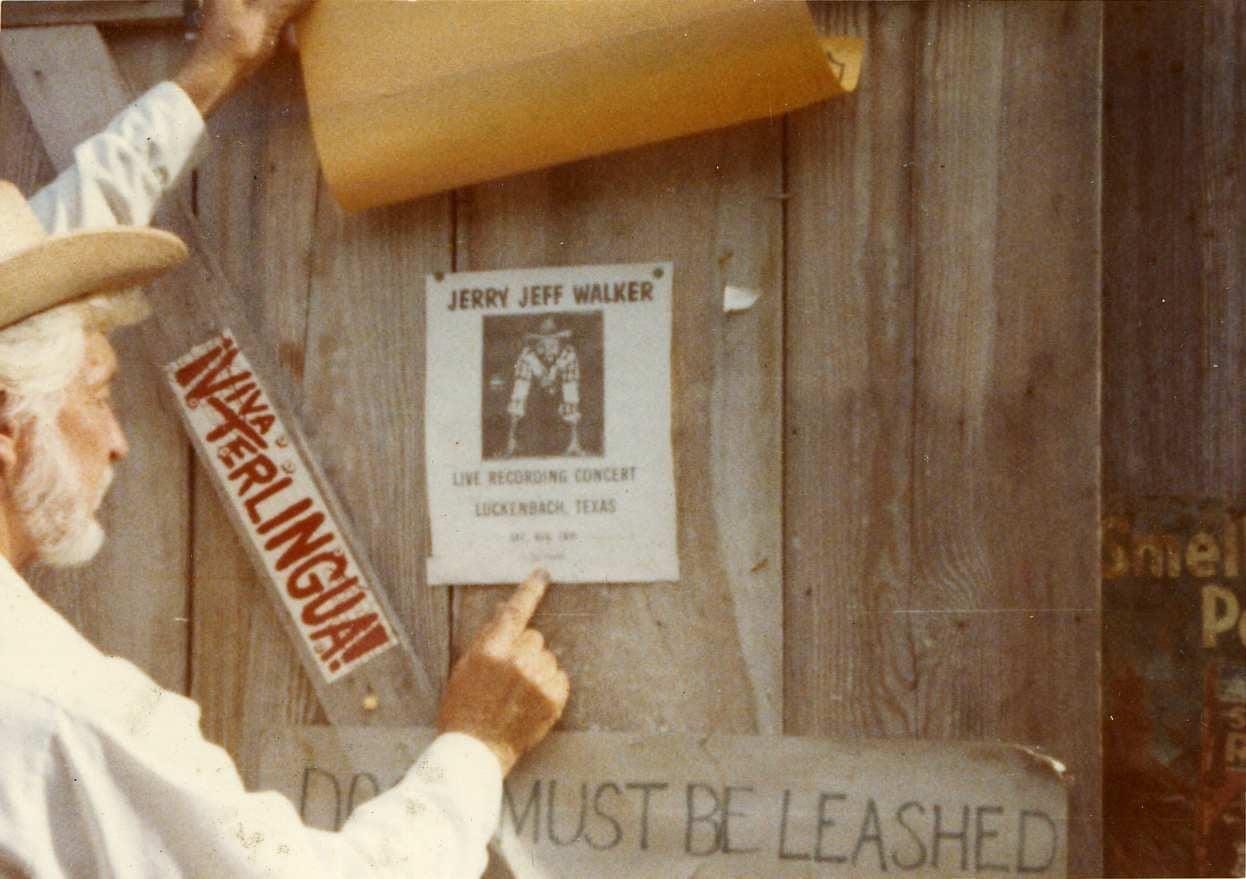

Jerry Jeff and the making of a raw 'cosmic cowboy' classic

¡Viva Terlingua! made Luckenbach famous and created a movement in Texas country music still going strong

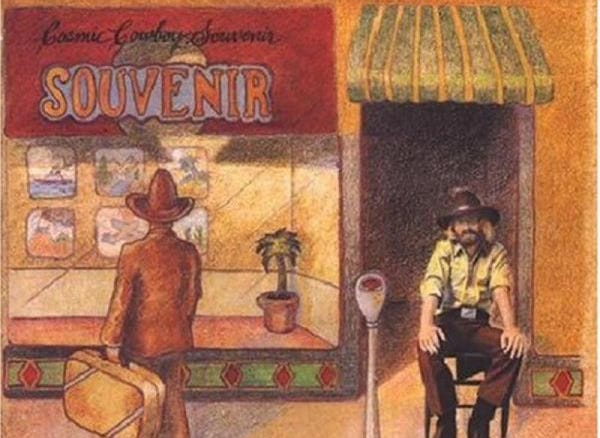

Michael Murphey gave it a name with his 1973 album Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir (A&M), but Jerry Jeff Walker gave it a sound and an attitude- frisky and carefree- later that year with ¡Viva Terlingua! (MCA). Both albums were recorded with the same band- Bob Livingston on bass, Gary P. Nunn on keyboards, Craig Hillis on guitar, Mike McGeary on drums and Herb Steiner on pedal steel.

The Austin Interchangeable Dance Band, as Steve Fromholz dubbed them, also backed Walker and Murphey when they played the Armadillo on a co-bill on August 2, 1972, 10 days before Willie Nelson’s legendary hippie/redneck christening. Murphey teamed with Willie a couple months later on the disastrous Armadillo Country Music Review (they couldn’t even spell “revue”), a six-city Texas tour which overestimated the number of cowboy hat-wearing hippies in Abilene, Wichita Falls and Lubbock. When Murphey called in sick on the hometown finale, a drunken Jerry Jeff filled in.

Oneonta, NY native Walker and Murphry, from Oak Cliff, had been mutual admirers since playing Dallas folk club the Rubiyat in the ‘60s. But two major label acts can share a band like they can a spouse, so sides were chosen, with Hillis and Steiner hitching a ride in “Geronimo’s Cadillac,” while the others became Jerry Jeff’s Lost Gonzo Band. John Inmon, who had been in Austin rock band Genessee with Nunn, replaced Hillis on guitar, and McGeary’s friend from California Kelly Dunn came sliding in with his B3 organ to make the Gonzos the best band in town.

“I knew John Inmon and Gary P. Nunn as rock n’ roll guys, not country” said Jay Aaron Podolnick of Odyssey Sound. Inmon played the Jade Room and New Orleans Club with Plymouth Rock and South Canadian Overflow, respectively, while Nunn was in highly successful cover band Lavender Hill Express with Rusty Wier.

Murphey, who stayed in Austin only two years, had legendary producer Bob Johnston (Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash, Simon & Garfunkel) in his corner. Hillsboro, TX native Johnston also managed the singer, who would add his middle name to the marquee to distinguish himself from the actor Michael Murphy (Manhattan, An Unmarried Woman).

It hurt Murphey most to lose from his band the versatile Gary P., also a great bass player, who he took with him to London for a month in early ‘73 while the others toured with Jerry Jeff. The duo did some gigs to publicize Murphey signing a European deal with EMI, plus the singer and then-wife Diana, a Brit, took their two-year-old son Ryan all around the U.K. to visit relatives. Nunn was left alone in cold, rainy London for much of the month.

That ended up being why Gary P. threw in with Walker. Not because he’d felt abandoned, but because he wrote “London Homesick Blues” in his loneliness, penning a classic “missing Texas” song (and the theme for Austin City Limits for 28 years.) Nunn debuted the number at the August ‘73 Terlingua concert in Luckenbach, and hearing 400 people singing “I wanna go home with the Armadillo” so loudly the first time they heard it made Gary P. realize he was in the right band. No way Murphey would let a sideman’s song take over his show. “That was Gary P. Nunn!” Livingston shouted at the end of the song, and Walker let it stay on the record.

He also kept “that song was by Ray Wylie Hubbard!” at the end of “Up Against the Wall Redneck Mother,” which, like “London Homesick,” was added to the live recording set as an afterthought. The original recordings of those two Texas music anthems were made without rehearsal. “When we played (‘London Homesick Blues’) at Luckenbach, that was the first time I’d ever heard it,” said Herb Steiner, whose steel guitar is all over the song.

Jerry Jeff Walker, who passed away in October 2020 at age 78, was a frequent flier by the seat of his pants.

He hated recording studios, found their precision soul-zapping. “When anyone mentioned ‘studio,’ I bought another round and looked for a hole to disappear into,” Walker told Townsend Miller of the Statesman in 1973.

His first album for MCA, the one with Guy Clark’s “L.A. Freeway,” was recorded in 1972 in the shell of the former Rapp Cleaners at 310 W. Sixth St. The General Audio Services studio of Steve Shields and Jay Aaron Podolnick was in the process of expanding into the cleaners space next door with gear they’d just bought from Wally Heider in L.A. Once the console had been installed, the renamed Odyssey Sound would be the first 16-track studio in Austin. “Jerry Jeff didn’t want to wait,” recalled Podolnick. “He said he’d rather record without any interference,” so the mics fed straight into the tape machine. This was unheard of in 1972, but raw and unfiltered suited Jeff Jeff just fine. The title on the masters sent to New York said Live From Rapp Cleaners, but MCA changed it to Jerry Jeff Walker and had the album mixed at Electric Ladyland, which began a contentious relationship between act and label. As if Jerry Jeff would have it any other way.

Walker’s close friend Hondo Crouch, a rancher/humorist 26 years his senior, bought a German ghost town outside Fredericksburg in 1971 with actor Guick Koock. They spent two years fixing up Luckenbach (pop. 3), restoring the dancehall and post office/bar. “Everybody is Somebody in Luckenbach” was the bumper sticker you put on your pickup if you were cool. Jerry Jeff wanted to record there the first time he visited, and his sessions put it on the map in a big way.

In August ‘73, the New Jersey-based Dale Ashby and Father mobile recording unit set up outside the dancehall and taped Walker and the band five nights without an audience. For the Saturday night, Jerry Jeff wanted the energy of a crowd, so he called radio stations and the newspaper and the place packed out, at $1 a ticket, with just a couple days’ notice.

Townsend Miller was there and wrote “seldom have I seen a crowd more boisterously enthusiastic,” but he wondered if producer Michael Brovsky could get any useable tape from the pandemonium. Oh, he got tape.

Jerry Jeff first drifted into Austin around 1964 when he played Bill Simonson’s club the id, on 24th Street near Guadalupe. It had no seats, just a rug that everyone sat down on. “The basic decoration was darkness,” Walker wrote in Gypsy Songman, his 1999 memoir. But the audience, curled up on the floor, “were telling me with their eyes that I was connecting with them.” Austin listens. Jerry Jeff took note.

After the id closed, Simonson opened the Eleventh Door folk club on Red River at 11th Street in late ‘65. That’s where Jerry Jeff would sing his most famous song “Mr. Bojangles” for an audience for the first time. It’s in his book. He had written the future classic the day before at 11th Door manager/ folk singer Allen Damron’s apartment near the club. It was late 1966/early 1967 (carbon dating is needed to accurately timeline Walker’s early years) and Jerry Jeff had caught a ride to Austin with his opening act from Kansas City. He was writing one night, every night, when “Bojangles” came tumbling out, “just one straight shot down the length of that yellow pad,” Walker wrote in Gypsy Songman. “On a night when the rest of the country was listening to the Beatles, I was writing a six-eight waltz about an old man and hope.” Damron was the first to record “Bojangles,” live to reel-to-reel, on the opening night of the Chequered Flag in Sept. ‘67. Damron managed that Rod Kennedy-owned club after the 11th Door (currently the offices of the Austin Symphony) shuttered.

Mr. Bojangles was the title of Walker’s 1968 album on Atco, but the big hit on it was by Nitty Gritty Dirt Band in 1970. Even though the song was a Sammy Davis Jr. showstopper for years, it was charged with “dance for us, boy” racism. It wasn’t about Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, however, but an itinerant white street-dancer in New Orleans, arrested, as Walker had been, for public intoxication.

Jerry Jeff’s alcohol consumption was legendary. His friend and writer Bud Shrake compared a Walker concert circa 1975 to a NASCAR race, “so full of thrills and suspense” and the possibility that he “might tumble off the stage and hurt himself.”

The Flag lasted three years, then reopened 18 months later as Castle Creek, with owners Tim O’Connor and Doug Moyes. Jerry Jeff’s home club had simply changed names and ownership when he finally moved to Austin in 1971. He played a lot of gigs at 1411 Lavaca, and got his buddy from Key West Jimmy Buffett booked.

I long dismissed Jerry Jeff Walker as a Texas version of Buffett, but it was actually the other way around. Ol’ Scamp Walker introduced Alabama native Buffett to the Florida Keys, and showed by example how to create an escapist lifestyle around your music.

Lung’s Cocina del Sur restaurant on Anderson Lane had an even bigger impact on Buffett’s career, introducing him to a frozen drink of tequila, triple sec and lime juice called the margarita in 1976. Before Jimmy could afford hotels, let alone build them, interior designer Victoria Reed put up him and some of his Coral Reefer band members at the six-bedroom house in Northwest Austin she shared with two other women. After dinner at Lung’s one night, Reed watched Buffett sitting on the deck of her house, strumming a guitar and singing some now-familiar words about flip-flops, pop-tops and a lost shaker of salt.

Have any bigger classics than “Mr. Bojangles” and “Margaritaville” been written in Austin?

“The mid-’70s in Austin were the busiest, the craziest, the most vivid and intense and productive period of my life,” Walker wrote in Gypsy Songman. He cut nine albums from ‘72- ‘78, but he also cut up a lot of white powder and looked up at whiskey bottles upside down. “Jacky Jack” was not only burning candles at both ends, he wrote, he was finding new ends to light.

Tired of their Oak Hill house being party central for druggies and hangers-on, wife/manager Susan left him for a few months.

“Don’t let your music kill you,” someone had told Jerry Jeff years earlier and he brushed it off. But in the late ‘70s, he took that advice to heart. 1979’s Too Old to Change was ironically titled, as JJW gave up drugs, whiskey, cigarettes and red meat the day he walked out of the studio and into an obsessively healthy lifestyle. In 1999, Shrake marveled that the former Ron Crosby was in his prime when everyone thought he’d be in his grave.

“We’re not in the music business,” Jerry Jeff Walker once said when asked what attracted him to Austin. “We’re in the business of having a life.”

A humble cassette of 1985 re-recordings of his greatest compositions revitalized Walker’s reputation as one of the greatest songwriters ever. Esteemed critic Glenn O’Brien championed Gypsy Songman in Interview magazine and other critics followed. But not me. Music is subjective and I just never paid attention to the three-named singer songwriters from the Jan Reid book.

But here it is 2022 and I can’t get enough of Jerry Jeff Walker. I still hate that “Hi, Buckaroos” shit, but there’s so much going on with seemingly simple songs like “Gettin’ By” and “Little Bird.” I never took the time to really listen before, but ¡Viva Terlingua! is as good as everyone thinks it is. Todd Snider, Robert Earl Keen, Pat Green and the rest of Terlingua’s offspring have good taste.

Thinking they were coming back to Luckenbach the day after the public concert just to listen to playback, the Lost Gonzo guys did some real good mescaline that morning. As the dancehall was swaying in the breeze, Jerry Jeff informed the band they were going to record one more song for the album. Thank God they knew this one! It was “Wheel,” kind of a Texas Hill Country take on “Old Man River,” with it’s wheel-keeps-rolling theme both ominous and comforting. The psychedelics kicked in at the right time, when little sounds become grandiose in the mind. Give it a listen.

Jerry Jeff was ragged, but right, once again. ¡Viva Terlingua! needed “Wheel” to go from really good to “classic.”

As for me, my life's too short

The wheel has carried me far

Around this world 100 times

By bus, truck, train, bike, or car

And just like the rest I roll on to my death

On a country road far from town

I stare by the wheel just as sure as I feel

That there won't be but one sound

That's the wheel that keeps spinning round

Rollin wheels, rollin' on

Takin us all on our way

I've recently gone through a similar Jerry Jeff reassessment....When I was a very little kid, I'd hear these first hand dispatches from Austin and Luckenbach from Guy and Susanna and Townes about this Jerry Jeff Walker character -- either chuckling over his antics or genuine expressions of gratitude for cutting their songs. This was up in Nashville -- the more cerebral, not as fun other half of a scene that should have all gone down in one town but didn't.....The years go passing by and I wound up at UT. By that time, Guy, Steve and Rodney were all more or less established....Townes was still struggling at the upper end of cult artist...It would take the Cowby Junkies and Sonic Youth to make him the multigenerational legend he is today. Anyway so in the Austin of 1988 I was astonished to find that Jeru Jeff, the outlaw's outlaw of my childhood. was beloved not just by the frat crowd but also their parents. I was simultaneously mortified and a little gratified that he'd made it.....And that was where he stayed in my mind until quite recently when I was given good reason to take a deep dive into some of his songs, and I agree. There's an innocence and vulnerability to some like "Little Bird" and a dark profundity to others like "The Wheel," as you mentioned. And the good timin' songs are just so infectious -- a friend of mine said that when he was a kid, he'd put on Terlingua or another early Jerry Jeff record, and it felt like he'd crashed some amazing party in the Hill Country that was nowhere near over when the needle spooled onto the label of side 2. He'd created a world of his own.

Michael

Otis Gibbs mentioned you today on his Youtube channel, so I thought I'd let you know, if interested, Otis will be doing a concert at my house in Wimberley Friday evening, January 13th, and you are invited. I continue to love your missives, thanks

-john moore