Jockeying for SRV at Deadhead Downs

Nine years of "Horse Racing and Rock and Roll" in Manor

In October 1974, the Grateful Dead played five consecutive nights (three shows?) at Winterland in S.F., then took a year and a half off, leaving Out of Town Tours out of its major client. So, Out of Town partner Frances Carr, an oil heiress from Corpus Christi, came back to Texas and bought a dormant 1960’s horse track 12 miles east of Austin called Manor Downs. She was “through with show biz,” she told the Statesman in March 1975, which is what the regulatory boards and conservative Manor neighbors wanted to hear.

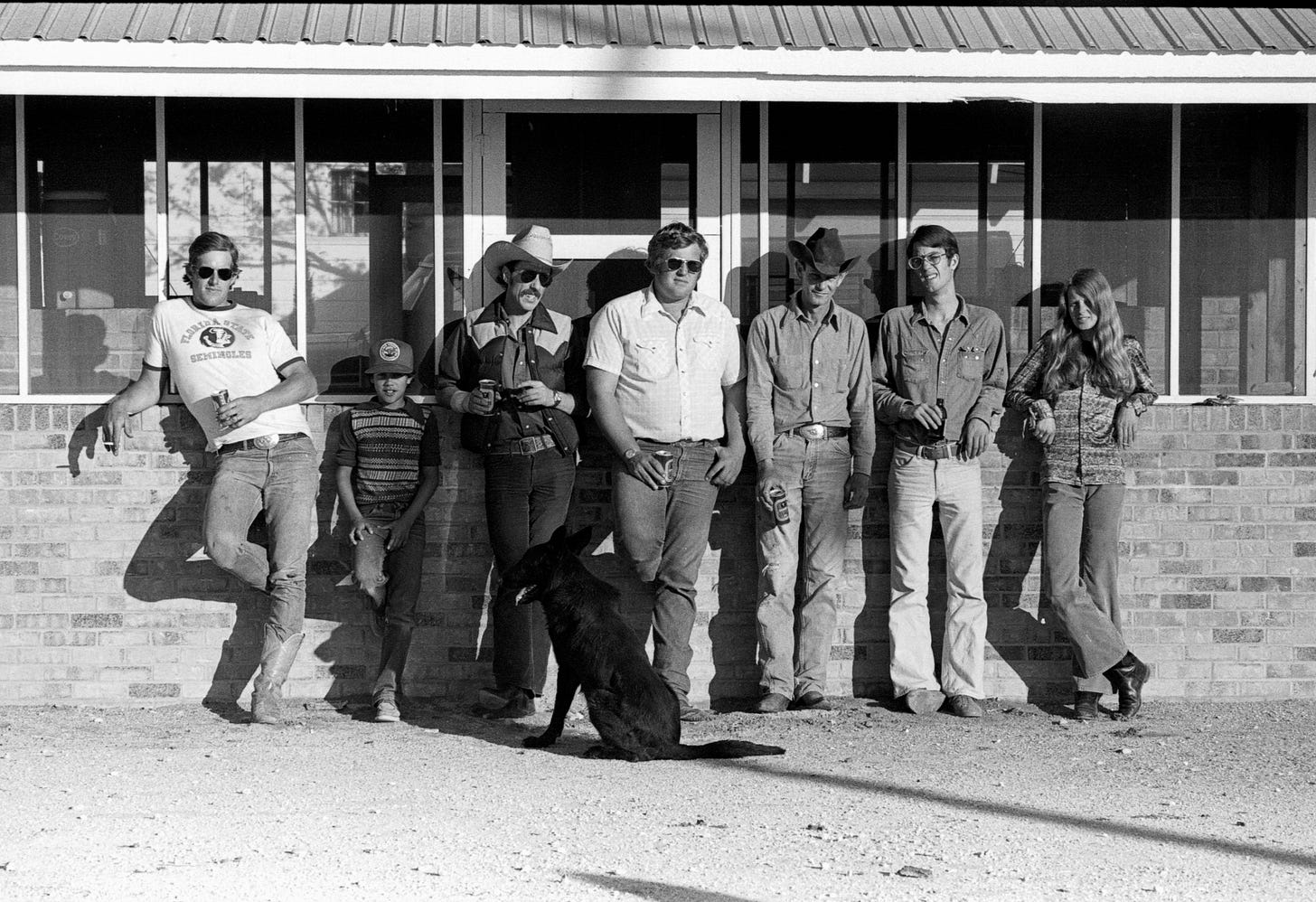

Managed by her boyfriend and O.T.T. partner Sam Cutler (of Altamont notoriety) the Downs would be an equine-training facility, with quarter horse racing on weekends. It was also pitched as the new home for the Travis County Fair and Livestock Show, which Austin’s City Coliseum proved woefully inadequate to handle. The renovated Manor Downs debuted in May 1977, and just five months later, the Dead played the infield of the racetrack for the first of five shows there in the next eight years. The track’s new slogan was “Horse Racing and Rock and Roll.” So much for Carr’s retirement from the music business.

In 1979, Manor Downs hired Bobby Hedderman, the former Armadillo booker as director of special events. He had a big first year with the Fish Outta Water Festival (a jab at the square Aqua Fest), featuring the Allman Brothers, Jerry Jeff Walker and Johnny Winter for $10 in July. Then came Waylon Jennings, with the original Crickets opening, and Cheap Trick, and the Kinks after that. Traffic was a problem, with only a two-lane road leading in, but parking was ample, beer was only $1 a cup, and outdoors under the stars had a lot more ambiance than the Super Drum.

For its effect on Austin music, however, Manor Downs is less significant for its big outdoor concerts than for what happened in its offices. In 1980, former Grateful Dead and Rolling Stones associate Chesley Millikin came to Manor to take over as general manager from his best friend Cutler, who eventually retired to Australia.

An avid horseman, first coming to North America for horse-jumping competitions, Dubliner Millikin also co-founded the Classic Management company with Carr. She had the money, he had the charm and connections. "Carry on" was his infectious sign-off.

Millikin’s first management client in 1966 was Kaleidoscope, which featured a young David Lindley, who he introduced to his former couch-surfer Jackson Browne. The next year Chesley returned to the UK to head the new London branch of Epic Records- and that’s when he met everyone in the British rock scene. He worked for the Stones in some capacity- or maybe he was just best mates with them, especially Charlie Watts.

“There were a lot of musicians here, but not much music business,” said writer Joe Nick Patoski of Millikin’s arrival. “Chesley helped legitimize Austin as a music town to the rest of the world." He let it be known he was looking for talent.

Manor Downs accountant Edi Johnson raved about a phenomenal guitarist toiling in the blues mines downtown, and took Millikin and Carr to see Stevie Ray Vaughan at Steamboat and the Rome Inn. His incredible guitar playing had Millikin speaking Chinese.

Ho lee fuk!

They signed a management deal in a hurry. Millikin got a copy of a VHS tape Steve Dean recorded of Stevie at the last night of the Rome Inn (4/20/80), and played it for Mick Jagger and Jerry Hall when they came down for a visit in April ‘82. A mightily-impressed Mick wondered when he and the rest of Stones, staying in New York, could see Stevie and Double Trouble live.

Millikin hastily arranged a private showcase at the Danceteria nightclub, attended by members of the Rolling Stones and a handful of others- maybe 40 people in all. Jann Wenner got wind and a photo and blurb appeared in the Random Notes section of Rolling Stone. It looked like SRV was going to join Peter Tosh on the roster of Rolling Stones Records, but Jagger passed, because the blues just didn’t sell.

That why Stevie languished in Texas clubs for 10 years. Yeah, he’s fantastic, but where does that go from here? The punks certainly didn’t like what Stevie and Double Trouble were playing, booing them heartily when they opened for the Clash on June 8, 1982 at City Coliseum. Not all of Chesley’s moves worked.

Jerry Wexler had already lost a lot of Atlantic Records’ money on Austin, so he didn’t sign him either after having his eyebrows singed by Vaughan at the Continental Club one Wednesday night in ‘82. Instead, Wex put in a call to Claude Nobs, who owned the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland. “I don’t have any of his music to send you,” said Wexler, “but trust me on this one.” It would be the first time an unsigned act would play the vaunted jazz festival.

Stevie Ray Vaughan’s life changed on July 17, 1982 in Montreux. Unlike bluesman John Hammond, who played solo acoustic in the concert hall named after Stravinski, Stevie and Double Trouble came out blazing with their full-on blues-rock set. It was the Austin club version of Dylan at Newport in ‘65, with scattered boos from the purists. But SRV didn’t flinch, and afterwards David Bowie stopped by his dressing room with praise, enticing the 27-year-old Texan to play guitar like that on the upcoming Let’s Dance album. Also blown away, Jackson Browne offered his studio in Los Angeles free of charge. Hammond called his father John Sr. with a new name for a discovery wall that included Billie Holiday, Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin and Bruce Springsteen. Stevie ripped under the radar no more.

Back home in Starfucker, TX, playing with David Bowie was considered the highlight of Stevie’s career, but Millikin foresaw bigger things for "Junior," as he called his charge. Vaughan was set to go on the Serious Moonlight tour with Bowie in ‘83, but with the Texas Flood debut coming out around the same time, Chesley said it made more sense to promote that record instead of being Ziggy’s hired gun. People in Austin thought Chesley Millikin was out of his fucking mind! You don’t turn down David Bowie when you’ve been playing for the same 50 people back home.

But Chesley was right, and by the end of the year, SRV was his generation’s new guitar hero, almost single-handedly resurrecting the blues while never forgetting the pioneers.

Millikin also put 16-year-old Charlie Sexton, who he didn’t manage, in a New York City studio with Ron Wood. That’s where Bob Dylan first met his future guitarist. "Chesley knew everyone," Frances Carr Tapp (who married Felix Tapp in ‘94), told me in 2001, when I was working on Millikin’s obituary. "He was incredible at putting people together."

Local blues singer Julie Burrell successfully switched her style to torch songs after Millikin gave her a Julie London album. It didn’t matter if he wasn’t going to make any money off you. The Irishman saw Austin as a land of unrealized potential and he lifted the scene wherever he could.

Meanwhile, the Stevie Express he’d engineered had become a runaway train, fueled by drugs and alcohol. A silver platter piled with cocaine was a studio necessity.

In the three years I wrote the “Don’t You Start Me Talking” column in the Chronicle I got some things wrong, but had to print only one retraction. I reported in 1986 that SRV had dropped Classic Management. Frances Carr called to say it was the other way around. Stevie’s drug problem had gotten so bad that Chesley couldn’t represent him anymore. “That sounds like a convenient version of what happened,” said Patoski, who co-wrote the Vaughan biography Caught In a Crossfire. I thought the same thing, but I printed what she told me and let people figure out who to believe.

“Chesley didn't want to be the manager that got the phone call that said Stevie was dead," said Widgeon Holland, the guitarist Millikin was grooming as the next Stevie when the manager was felled by emphysema at age 67. When Millikin got the diagnosis eight years earlier, he moved for his lungs to Indian Wells, in the Palm Desert of California.

At Manor Downs in ‘86, the breakup with SRV was set aside for the big news that Texas legalized pari-mutuel wagering, to take affect in ‘87. With the big focus on getting the track in shape for thoroughbred racing, Carr really was done with show business this time. Millikin began managing an MS-stricken Ronnie Lane of the Faces, who he convinced to move to Austin.

Farm Aid II, which doubled as Willie’s Picnic, was the last big show at the Downs on July 4, 1986. There was a Saragosa Tornado benefit in Aug. ‘87 starring Waylon Jennings, Neil Young, Steve Earle and more, but after only 700 tickets were sold it was held in the paddock area.

The Grateful Dead played only two more concerts in Texas- Houston and Dallas in ‘88- after their last show at Deadhead Downs. Jerry Garcia died in August 1995.

The horse-track in Manor closed in 2010. The 146-acre property Frances Carr owned with brother Frank William “Billy” Carr Jr. was sold in 2021 to a Dallas developer of industrial parks for an undisclosed amount.

From Austin Music Is a Scene Not a Sound coming on TCU Press in Spring 2024.

Yep I was there as Julie's bassist with Chris Duarte and the late great Jeff Hodges. We rehearsed in the 2(italic2)P (too lazy to) little bar there. This big black guy started hanging around (Medlow), singing Hendrix and James Brown. Then we hit it off at the Black Cat thanks to Paul Sessum's match-making - no more Julie. Not sure where she is now?...and that Millikin was a charmer.

In August of 1987 I saw the Saragosa Tornado Benefit concert. Neil Young, Los Lobos, Steve Earle Waylon Jennings and others played. Sparsely attended as I remember.