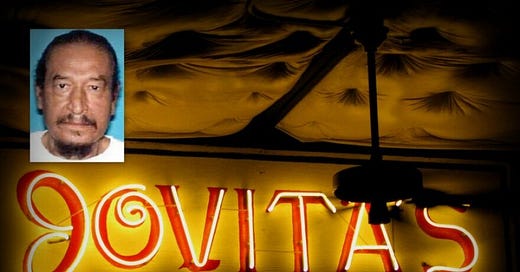

Jovita's was built on community, backed by heroin

Drug ring was run out of the musical home of Don Walser, Cornell Hurd and others

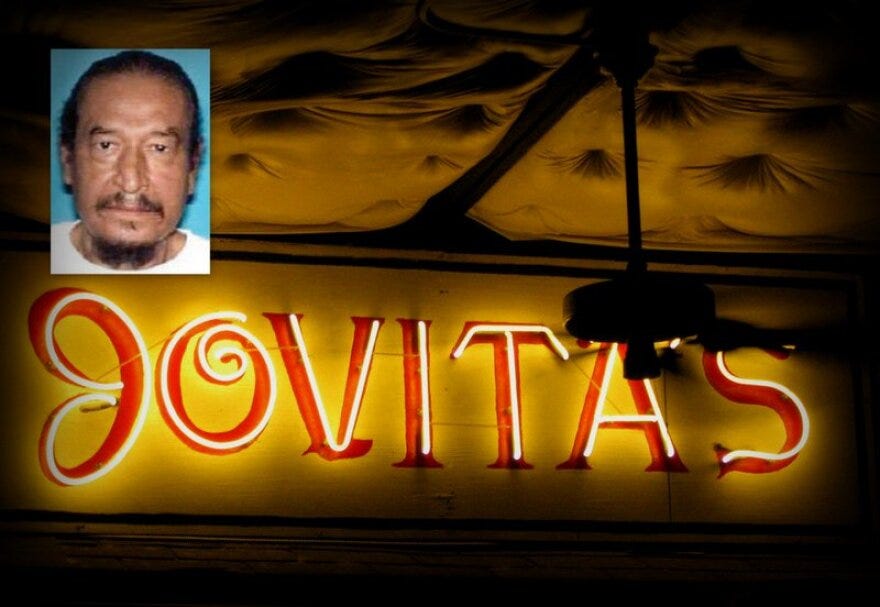

The Austin music community was stunned on the morning of June 22, 2012, when the news broke that Jovita’s, a beloved Tex-Mex restaurant and music venue on South First for 20 years, had been raided and shut down as a heroin distribution hub. After a yearlong investigation by the FBI and APD dubbed “Operation Muerte Blanca,” owner Amando “Mayo” Pardo was named ringleader, with 14 of his associates also arrested. Authorities said Pardo, who served three prison sentences in the ‘70s and ‘80s, including two for murder, was a member of the Texas Syndicate gang. What the fuck?!

After the shock came the jokes about “addictive tacos” and “jonesing for Jovi’s hot sauce.” Even humor-allergic Texas Monthly got into the yuks, writing, “Would you like some black tar heroin with your enchiladas?”

The public had no idea Pardo was selling up to $6 K a day in skag, because he was seen as an impassioned community leader, who used his business to host fundraisers, spearhead voter registration efforts and promote Mexican American pride and unity. The hypocrisy that this good man would destroy families for a living was astounding. But the Texas Syndicate is not a club you can quit.

One way drug dealers raise suspicion is when neighbors see a lot of cars coming and going at all hours and notify police. But Pardo’s dealers just parked at the restaurant and walked across a little bridge to Milton Street, where he owned a house. Occasionally, the restaurant was used to cut and package the heroin in balloons, which wholesaled in packs of 18, but most of the illicit activity was on Milton, according to police. Pardo’s two operations- the legal and the criminal- were separated by East Bouldin Creek and, perhaps, his mindset.

Tough living showed on his face, and was heard in his voice, but Pardo’s influence seemed so positive, putting his kids through college (including law school for son Amos) and helping his employees pursue higher education. He gave Austin musicians a stage and a guarantee- putting a combined $100,000 a year in their pockets. Plus tips.

“Mayo was constantly upgrading the place,” said Cornell Hurd, whose 10-piece band played there every Thursday for 14 years. Jovita’s sound system was one of the best Don Walser (Tuesdays) ever yodeled through.

But to show Pardo’s dual identity, he’d drive Jovita’s kitchen worker Tatiana Huang to college each day after her shift, but at night use her to cut and package heroin. When Huang went to trial in Feb. 2013, her attorney said she was an addict, not a dealer, who needed rehab, not prison. She received a four-year sentence.

Mayo Pardo died of liver cancer in January 2013 at age 64, a month before the trial, proclaiming his innocence to the end. He had been diagnosed two years earlier and was improving due to holistic treatments, but seven months in jail “was a death sentence,” according to Hurd. Pardo was denied bail until he was sent home to die three days later.

Mayo was raised in the same part of South Austin as the restaurant/bar he named after his sister. He was a neighborhood tough who, in 1971, gunned down a pair of cousins at Motif Lounge on South First (later G&S Lounge). Because the main eyewitness walked back earlier testimony, a 22-year-old Pardo was able to plead guilty to one of the murders for a 12-year sentence that ended up being four years served. A gun charge sent him back to the joint for three years. Then another murder, in Houston in 1983, put him behind bars for another four years.

The FBI claimed Pardo’s life as a heroin dealer started with his ‘87 release. Five years later, he was able to buy the former Big Ben’s beer joint at 1619 S. First St., putting the title of the land in the name of wife Amanda and the business in sister Jovita’s. Mayo’s place opened in Dec. 1992 with Johnny Degollado, Lisa Mednick, and David Rodriguez (with young daughter Carrie on violin). The Tailgators were the first big regular draw, setting the stage for many roots rockers to follow.

After Henry’s Bar & Grill (6317 Burnet Road) closed on Halloween 1992 to make way for an Auto Zone, that hardcore country scene followed Don Walser and Cornell Hurd to Jovita’s.

Poet activist Raul Salinas was Jovita’s first booker, but he left after a year to spend more time with his Resistencia Bookstore. His neighbor at the 2210 S. First St. strip mall, artist Joyce DiBona, would become close to Pardo, painting the murals at Jovita’s and eventually moving her studio into a house he owned behind the restaurant. Some say the two had a romantic relationship.

DiBona got her brother-in-law Sam Loy, a sound engineer, involved with Jovita’s when Pardo’s vision extended to starting a record label. "Joyce was such an advocate for Mayo,” said Sam Loy, who sold his recording studio equipment to Pardo for $25,000 cash when he relocated in 1999. Loy came back in 2001 to run it.

“Mayo would never sign his name to a piece of paper, and he only paid in cash,” said Loy, who had a verbal agreement to get a piece of the revenue from CDs he produced. The one and only release on Jovita Records was by a reunited Vanguards, a swan song for drummer John “Mambo” Treanor, who passed away less than a month after the July 2001 recording of Live at Jovita’s.

“When the CDs were ready to be picked up, Mayo came to pay for them,” Loy recalled. “And he just took the box with him and said to tell the band that if they want any copies, they’re five dollars each. I told Mayo ‘that’s not the deal we had,’ but he didn’t care.” Loy quit the next day, after coming by Jovita’s to gather his belongings. “I’m still kicking myself for not taking the hard drive,” he said of the hours of recordings he’d made during his year at Jovita’s. One session with the South Austin Jug Band, recorded at Momo’s, had already been mixed and was set to be mastered for release, but Pardo held it hostage. When I wrote about it for the Statesman, Mayo told me he didn’t want anyone rummaging through his computer. SAJB considered suing Pardo to get their masters, but instead took a refund from Loy and rerecorded with Rich Brotherton. “I had to give the band back $2,000, which really hurt because I was broke and unemployed,” the engineer said.

Though Pardo and Loy got along well at first, the relationship withered. “I could eat for free, so I’d have one crispy taco a day,” Loy recalled. “Mayo lit into me over it, saying ‘You just come here to eat my food!’ He’d say ‘my dishwasher could do your job!’ It was that Machiavellian thing about controlling people by never letting them feel like they have any importance.” Loy said Mayo’s bible was The Prince.

Others knew a different Pardo. “Mayo and I were about as close as any two people could be,” said Brad Reed, who booked Jovita’s during it’s mid- ‘90s/early ‘00s glory years. “We were like father and son, and not one time did I see any evidence of what he was accused of doing.” Hurd testified to the same thing in court.

Reed started working for Pardo just two years out of Crockett High School. “I got a job at Grizwald’s, next door to Jovita’s, so I got know everybody there,” said Reed, who helped original booker Salinas for a year before Mayo gave him the job in ‘93. “This was during the rockabilly, retro-country heyday so we booked High Noon, Dale Watson, Wayne “the Train” Hancock, Marti Brom, Madcat Trio, Junior Brown- those kinda bands,” in addition to the popular Walser/Hurd residencies.

“But, by far, our biggest band was the Gourds. They would play once every two or three months and it was crazy,” Reed recalled. This was before 2000’s Bolsa de Agua made them outgrow the room. “The bar would run out of beer and I’d have to sell it out of our walk-in cooler.”

Reed was hurt in 2007 when Pardo installed DiBona as co-booker, so he left to work at Patsy’s Cowgirl Cafe. DiBona passed away from cancer around 2015.

Nobody went to Jovita’s for the food, except Chicago transplant Don McLeese, who also loved that the shows were usually over by 10 p.m. Whenever I came to Austin for a visit from Dallas, Jovita’s was the designated meeting place. But it wasn’t my scene because one of my many food phobias is watching a band when people are eating. Especially with those messy Tex-Mex plates. But I’d come out for accordion master Esteban Jordan even if the audience was butchering goats. Jovita’s was one of the only clubs in town that would meet Jordan’s $1,000 asking price, even though the room wasn’t big enough to make that back at the door.

Pardo was a straight-shooter who carried himself as a guy you didn’t want to mess with, but that was part of his appeal. Especially when he seemed such a pussycat deep down. Mayo was the music scene’s Danny Trejo, which is fitting because the company of Robert Rodriguez (who’s directed Trejo in several projects) recently bought the land at 1619 South First, with plans for a four-story, multifamily, residential building, with retail on the ground floor.

Good one, Michael. I saw someone I knew busing tables there. After Mayo got busted I realized she was stone high that day and remembered that she had really struggled to kick. It was a kick in the gut when it dawned on me.

I have owned Don's Automotive across the street for 43 years. When I first met Pardo it was instantly obvious that he was a screaming asshole. Previously that location was a neighborhood laid-back beer joint called 'Big Ben's." During my first and last conversation with Pardo I mentioned that Big Ben and I were friends and always tried to help each other out. Pardo said "Well this isn't Big Ben's." making it very clear he wanted no part of a cooperative relationship. So I would see him directing people to park in my lot when theirs overflowed -- never offering so much as free tacos in exchange. I posted signs so I could have the cars impounded. I would says that the fate of dying of liver cancer while incarcerated is something I would never wish upon anybody -- well....with one exception.