When native East Austinite Josephine Dukes heard that Janet Jackson’s new album in 2004 was called Damita Jo, she was stunned. The only Damita Jo she knew was her cousin, a dynamic jazz singer who had a couple of pop hits in the early 1960s.

Then Dukes started putting it all together. Damita Jo (DeBlanc) had told her that Janet Jackson’s mother Katherine was a fan who named her daughter Janet Damita Jo Jackson. That info’s right there in the funeral program for Damita Jo, who died in Baltimore on Christmas Day 1998 at age 68, of respiratory illness.

A 4-foot-11-inch spitfire who lit up showrooms and living rooms alike, the Austin native had hits with “answer songs” to “Save the Last Dance For Me” by the Drifters and to “Stand By Me” by Ben E. King. But she really wanted to be the next Ella Fitzgerald. She could scat like her idol.

Born in Austin on Aug. 5, 1930, the only child of Creole chef Herbert DeBlanc and schoolteacher Latrelle Plummer DeBlanc, Damita Jo was dancing and singing as soon as she could walk and talk. “She was a natural entertainer, the life of the party,” Josephine Dukes recalled. Her comedic flair later impressed Redd Foxx, who made her a regular on his 1977 TV variety show.

Damita Jo’s father, who grew up speaking French in Iberia, La., and never lost the accent, enlisted in the Navy during World War II and was stationed in Santa Barbara, Calif., where Damita Jo attended high school. But she’d often return to Austin, where her grandmother Mathilde DeBlanc had a big house at 1010 Olive St.

While a student at Samuel Houston College in 1949, Damita Jo sang regularly at Dinty Moore’s, a cafe bar on W. Sixth and Colorado Streets owned by transplanted New Yorkers Dave and Flo Robbins. After that club was torn down in 1950 to make way for the American National Bank building, Dave and Flo opened the Manhattan Club at 911 Congress Avenue, which eventually evolved to a kosher deli.

“I just adored Damita,” gushed Josephine’s daughter, state Rep. Dawnna Dukes of Austin. “She was the sweetest, warmest person you could ever meet. She’d say ‘Hot dog!’ and slap her thigh and everybody was ‘darlin’ and ‘sweetheart.’ ” Dawnna Dukes has become the DeBlanc family historian in recent years, tracing the Austin clan as direct descendants of Louis Antone Juchereau de St. Denis, a French explorer from Quebec who founded Natchitoches Parish in Louisiana in 1714.

In an entirely coincidental aside to the Janet Jackson/Damita Jo connection, Luther Simond, married to Damita Jo’s aunt Ada DeBlanc Simond, was an assistant principal at Norton Junior High in Gary, Ind., in 1966 when Janet was born. “I knew the family well,” Simond said of the musical tribe that put Gary on the map. “Those (Jackson) boys started off singing in the church choir. Then, when they got their act together, I called my stepson (Supremes musical director Gil Askey) in Detroit and said, ‘You need to come down here and check these guys out.’ “

Damita Jo’s life had its share of tragedies. Her mother died when she was 19 and she moved back to Austin, delaying dreams of Hollywood stardom for the support of family. In 1970, her father was shot to death at the Deluxe Hotel (1101 Navasota St.) by a man he’d lent money to who didn’t want to repay. Eight months pregnant and living in Baltimore, a grieving Damita Jo was forbidden by doctors to travel to the funeral.

The daughter she gave birth to in 1970 died of sickle cell anemia at age 3. Damita Jo was on the road when she got the news. After that, she rarely toured and doted on her only son, John Jeffrey Wood, whose father, Biddy, married Damita Jo in 1961 and managed her career.

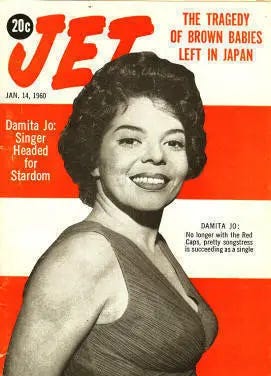

Her first husband was band leader Steve Gibson, 16 years her senior, whose Red Caps featured Damita Jo as lead vocalist. They had a Top 20 hit in 1952 with “I Went To Your Wedding” (written by Jesse Mae Robinson of Jasper, TX), which was covered with greater success by Patti Page. The couple divorced in 1958.

Signed to a solo deal with Mercury, Damita Jo hit the pop charts in late 1960 with “I’ll Save the Last Dance For You.” Six months later she had a No. 12 pop hit with “I’ll Be There,” a response to “Stand By Me.”

The pop hits stopped there, as Damita Jo transformed herself into a portrait of elegance, singing jazz standards at swanky bistros and casino nightclubs for the remainder of her career. She recorded several albums for the Mercury and Epic labels.

Mayor Lester Palmer declared May 9, 1967 “Damita Jo Day” when the singer returned to her hometown to perform at Municipal Auditorium. Ticket sales were slow, however, and promoters couldn’t pay Damita Jo and her 20-piece orchestra the full amount, so the show was delayed over an hour as an arrangement was worked out. The singer ended up getting a standing ovation and four curtain calls, according to Nat Henderson’s review in the Statesman.

Damita Jo retired from performing in 1984, after an eight-week run with Joey Bishop in Atlantic City.

“She was everyone’s favorite person,” Dukes recalled. “She was the family’s little china doll.”

KENNY DORHAM AND GENE RAMEY: Be-Bop royalty from L.C. Anderson High

This town is a country and blues burg, a rock-without-borders haven, a place that embraces songwriters who can make poetry from their past. But you don’t hear much about Austin’s legacy as a jazz town. It’s quite amazing, then, to realize that a pair of Austinites- trumpeter Kenny Dorham and bassist Gene Ramey- not only backed the likes of Charlie Parker and Lester Young, but played on many of the late-’40’s and early-’50s Thelonious Monk sessions one critic called “among the most significant and original in modern jazz.” To go from the all-black L.C. Anderson High School in East Austin to 52nd Street in Manhattan and play with the best is a trek that only talent can guide. But Dorham and Ramey, who both picked up a lot of session work by knowing how to best shade the outline of the spotlight, are not widely known. Dorham was in the shadow of the top trumpet players of the bop era: Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie. But he’d settle for the “thinking man’s trumpet player” tag.

Ramey (1913-1984) went to L.C. Anderson High before it had a band, but got his musical education following Eddie and Sugar Lou’s Band, transplants from Tyler, featuring Oran “Hot Lips” Page on trumpet. When Ramey went to Kansas City for college he met Hot Lips’ half-brother Walter Page of the Blue Devils, who taught him to play bass. He got his big break in 1937, joining the Jay McShann Orchestra, then convincing the bandleader to hire the brilliant, but irresponsible Charlie Parker on sax. OK, said McShann, but Ramey was in charge of Bird’s sax after gigs so it wouldn’t be pawned.

Ramey didn’t drink or do drugs and was naive to the demon ways of an addict. “We were coming from Port Arthur to Austin for a date,” Ramey told John Bustin in 1964, “and Bird and Walter Brown, the blues singer, got sick. They were sweating and moaning and looking real bad, so I called my mother and told her I was bringing home a couple of sick boys from the band and for her to get a doctor.” After Parker and Brown were treated, the doctor took Ramey aside and scolded him for bringing junkies to his mother’s home. “I was shocked because I hadn’t even realized that was what was wrong with them.” Parker died of a heroin overdose in 1955 at age 35.

Eleven years younger than Ramey, Dorham was part of a group of young horn-blowing cats who’d sneak off after band practice, away from the authoritative glare of Sousa-lovin’ band director B.L. Joyce, to play improvisational jazz in the backyard of Roy and Alvin Patterson at 1709 Washington Ave. Also in that horn circle were Gil Askey, who would go on to be the top horn arranger at Motown; trombonist Buford Banks (Martin’s father); and a pair of swinging trumpet players, Paris Jones and Rip Ross.

In a 2004 interview, Alvin Patterson (who would replace Joyce as Anderson’s band director in 1955) told me Dorham was “very thoughtful and perceptive” and would often defer to the older players, especially Hermie Edwards, who everyone knew as the baddest horn player on the Eastside.

After high school, Dorham attended Wiley College in Marshall, where he majored in chemistry. But after only a year in college, Dorham was drafted into the Army. He was discharged in 1943.

Dorham’s first gig was in California with the Russell Jacquet Orchestra, according to Dave Oliphant’s Texan Jazz (University of Texas Press). Dorham got his break in 1945 when he replaced Fats Navarro in Billy Eckstine’s orchestra, the first bop big band, from whose ranks flowed the likes of Parker, Davis, Gillespie, Dexter Gordon and Sarah Vaughan.

Patterson met up with his former marching band mate when Dorham was playing with Eckstine’s band in Boston. “He used to copy Erskine Hawkins,” Patterson recalled of the Anderson days. “Kenny loved to play that ‘Tuxedo Junction.’ But he started getting into his own thing.”

On Christmas Eve 1948, Miles Davis couldn’t make a gig with the Charlie Parker Quintet, so he recommended Dorham as a replacement. The gig lasted two years, including a sensational stint in 1949 in Paris, at that city’s first international jazz festival.

Although Dorham played with Parker on the sax great’s final public performance in 1955, he spent most of the early ’50s freelancing for Monk, Bud Powell, Sonny Stitt and others. In 1954, he co-founded the highly influential Jazz Messengers with Art Blakey. Ramey was also a Messenger for a time. The Anderson High alums crossed paths often.

Later, Dorham led several of his own groups, recording such highly regarded albums as Afro Cuban in 1955, Jazz Contrasts in ’57, and his most highly regarded LP, Una Mas, in ’63.

“In Miles’ autobiography, he writes about what an underrated player Kenny Dorham was,” said Thomas Heflin, whose New Six Jazz Project played a birthday tribute to Dorham at the Elephant Room in 2008. “He wasn’t flashy like Dizzy (Gillespie) or quite as stylish as Miles, but there was so much lyricism in the way Dorham articulated notes.”

With such tenderness and vulnerability in his dark tones, Dorham has been called the most poetic of trumpet players. “He embodied the Blue Note era,” Heflin said, in reference to the signature label of 1950s and ’60s jazz.

He was also a bluesy singer on occasion, wrote the jazz standard “Blue Bossa,” and helped discover and nurture young talent such as tenor sax player Joe Henderson.

Eastside band icon Patterson, who passed away in 2007, was able to hang out with Dorham one last time, at the 1966 Longhorn Jazz Fest at the old Disch Field. Also booked at the festival were Coleman Hawkins, Miles Davis, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Elvin Jones, Dave Brubeck, Stan Getz and Austin born/ Alabama-raised Teddy Wilson.

Dorham and Ramey, along with Nat King Cole’s guitarist Oscar Moore, are the greatest representatives of Austin-raised talent to the jazz world because their playing was in service to the song. Counting Wilson, there’s not a musical genre that Austin has produced more icons in than jazz.

Dorham died of a kidney disease in 1972 at 48. Ramey retired to a farm in Williamson County, where he lived out the last eight years of a long and fruitful life. Moore died in 1981 at age 64.