MAJER PLAYER

Carlyne booked Soap Creek, managed major label acts, founded the Texas chapter of the Grammys, and put out fires for SXSW

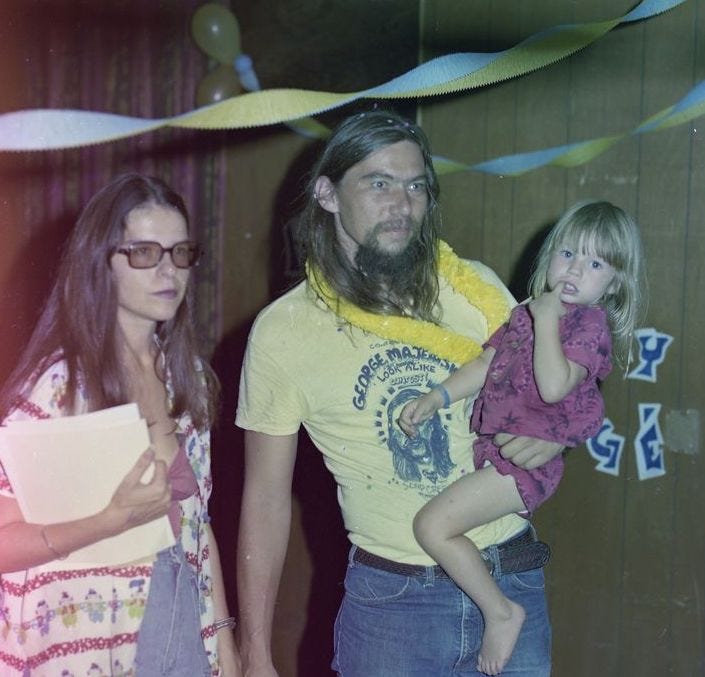

She was an Armadillo “Sweathog” who cleaned up nice (for free admission), and he co-owned Oat Willie’s with Doug Brown. Carlyne and George Majewski got married in 1971 and were looking to run their own club, especially after the Dillo decided to hold off on a proposed cabaret configuration- a club within a club that Carlyne had hoped to manage. She and George filled the cozier venue void, buying the Rolling Hills party barn in West Lake Hills from bassist Alex Napier. The former Carlyne Gough had just given birth to son Ross, but there was no time for a maternity break, as the couple went to work on opening Soap Creek Saloon, which debuted March 24, 1973 with Conqueroo and Whistler.

George was the face of Soap Creek and ran the club, while Carlyne booked it, as “Carlyne Majer,” a name that would later become known in the music industry as the manager who could get her acts signed: Marcia Ball (Capitol), Rank and File (Slash/Warner Brothers), the Wagoneers (A&M), Kelly Willis (MCA), and Lone Justice (Geffen). She was hands on, up to a point. Asked if she had to fire Alejandro Escovedo from Rank, she says, “I managed bands. Whatever they did among themselves was their decision.”

In 1994, Carlyne became the founding executive director of the Texas chapter of National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences- the folks who bring us the Grammys, whether we want them or not. That branch, which grew to 800 members in five years, is a big reason there are now Latin Grammys.

With a hard Texas accent on the fog-cutter spectrum, Carlyne was a tough negotiator with Southern charm, a sharp hayseed with a gold-star-encrusted tooth. “You want fair?” she’d tell whiners in her midst. “Fair’s in Dallas.” Her stage was the record label office, where she was an alt-country Texas Guinan, brightening up the room with her brass. When she’d leave Geffen, everyone would poke their heads out and imitate her “baa y’all!”

Future Warner Brothers exec Bill Bentley was one of Carlyne’s assistants circa 1977, along with future DJ Jody Denberg. “We had a small office in her house on Hollywood Avenue (in Cherrywood) and it was a trip every day watching and listening to her hustle and bustle,” Bentley said. “She made things happen, that's for sure.”

Born in 1947, Carlyne grew up in College Station, where her mother was head nurse at Texas A&M Hospital, where you went for your bonfire and hazing injuries. Carlyne’s twin brother Carl Merl went full Maroonatic, even playing football for the Aggies, but Carlyne bolted to our counterculture haven after only a semester at A&M. Austin had been a city of escape during her high school years, where she would buy peyote, which was legal in the ‘60s, sold openly at Hudson’s Cactus Nursery.

She met George, a Tenafly, NJ native, in her first of six years at UT. After he graduated with a business degree, ending his college deferment, Majewski was drafted in ‘68 and shipped off to Vietnam. Carlyne bought an Indian motorcycle from Jack O’Leary’s on South Lamar, and moved to San Antonio to race in motorbike enduro competitions. Both occupations prepared the soon-to-be couple for the obstacle course- a dirt road with potholes the size of artillery strikes- that led club goers to their “Honky Tonk In the Hills.”

When the Majewskis opened Soap Creek, other live music clubs in town included not only the Armadillo, but Castle Creek, Split Rail, One Knite, Black Queen, Flight 505, Broken Spoke, South Door, Saxon Pub, Toad Hall, River City Inn, Bevo’s Westside Tap Room, Continental Club and Mother Earth. Why would anyone drive the hell out to West Lake Hills to party?

The isolation was actually a plus, and nobody worried about DWI in the ‘70s, when the legal blood alcohol limit was .15. You had to want to be out there, which made the people feel safer with each other. The other thing that set Soap Creek apart from most other music venues in town was that they served mixed drinks. The Armadillo only had beer and wine, which was fine with frats and tourists, but Soap Creek had a slightly more mature audience. And it’s where the musicians hung out, including Willie Nelson, who lived a mile from Soap Creek when it opened. “Willie was my mentor in the music business,” says Carlyne.

Nelson’s Shotgun Willie, one of the opening salvos of the outlaw country movement, came out two months after Soap opened. Willie’s deal with Atlantic Records gave him the creative control denied him in Nashville, and he made full use of it on the 1974 followup Phases and Stages, considered by many to be his best album. But neither record sold, so he was dropped by Atlantic. All this was going on when he was hanging out at “Dope Creek.”

Doug Sahm could empathize, as he was also two-and-through at Jerry Wexler’s Atlantic. His 1972 dream project Doug Sahm and Band (featuring Bob Dylan, Dr. John, Flaco Jimenez and others), and the Texas Tornado followup, registered lukewarm sales. After a token European tour in early ‘73, Sahm came back to Texas thinking nobody got him. But then he packed Soap Creek on successive nights with people who REALLY got him. He had found his Groover’s Paradise.

“If more people had a stable place to come back to, more brotherhood,” Sahm told the Statesman in ‘73, “it might’ve saved people like Jimi Hendrix.”

Sahm rented a big limestone house a couple hundred yards away, and became Soap Creek’s self-appointed (unanimously-approved) musical adviser. He turned the scene onto Freddy Fender when his Sir Douglas Quintet covered “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights” on 1971’s The Return of Doug Saldaña. “This is for Freddy Fender, wherever you are,” was Sahm’s intro dedication. Carlyne made it her mission to find the Latino Aaron Neville, who had semi-retired from music after prison for a low-level marijuana bust. She found him working as an auto mechanic in Corpus and wired him $200 to get to Austin. With Sahm opening, the club sold out and “El Bebop Kid” had a nice payday. The next year Freddy Fender was the hottest thing on the charts with “Til the Next Teardrop Falls.” And it wouldn’t have happened without Doug Sahm, Soap Creek, and Sahm producer Huey P. Meaux.

Willie quickly outgrew the Creek as a viable venue, so Carlyne promoted a concert- the Austin Longhorn Ball- featuring Willie, Sahm and Alvin Crow at the 6,000-capacity Municipal Auditorium in ‘74. She was stage manager at Willie’s Picnic that year, too. Majer never doubted her place in the male-dominated music business. And neither did the men she dealt with.

Willie finally conquered the country music world with 1975’s Red Headed Stranger, leading a gang of fellow country outlaws, who brandished anti-Nashville sentiments all the way to No. 1. Music Row was shaking in its boots at the Austin-headquartered uprising. The Country Music Association decided to make peace by moving its annual board meeting from Nashville to Austin in April 1976. Willie told them to stick that olive branch, um, over there in the vase. Outlaw, hell. Willie wanted as many people as possible to hear his music. He’d play a private concert for the music business bigwigs at the 250-capacity Soap Creek, so they could really understand what was goin’ down in Austin. Willie would test their tolerance by planting a kiss on the mouth of his co-star Charley Pride. That’s the legend, at least.

The “Home of the Stars” went all out for the CMA, with Big Rikke Moursand, an Armadillo legend as “the Guacamole Queen,” cooking her famous shrimp enchiladas before the show. Anybody who wanted to, met Coach Darrell Royal, country music’s biggest fan. “Everybody had the time of their lives,” says Carlyne, who also got Marcia Ball, Floyd Tillman, Pee Wee King and Milton Carroll on stage that unforgettable Tuesday night. “Next time you come to Nashville,” legendary WSM/Grand Ole Opry CEO Bud Wendell told Carlyne, “let me show you around.” When she took him up on it, he took her to meet Dolly Parton at a TV taping.

A few months later, Willie and Waylon would each win three CMA awards for “Good Hearted Woman” and the album Wanted: The Outlaws. Carlyne was there to watch Willie perform live- before losing Entertainer of the Year to Mel Tillis. The old regime took that one.

Carlyne’s ATS management (Austin Tejas Sounds) formed in ‘76 to represent Marcia Ball, the former Freda of the Firedogs, the first hippie band to play the Broken Spoke. In June ‘77, Ball signed to Capitol Records, where she made Circuit Queen with Guy Clark producer Neil Wilburn. Carlyne’s next band was L.A. cowpunk pioneers Rank and File, who’d moved to Austin in ‘82. Best thing she did for them was to get the Everly Brothers to cover “Amanda Ruth,” via a sub-publishing deal with a European company. On Rank’s reco, fellow Angelenos Lone Justice hired ATS the next year.

It wasn’t hard getting a record deal for Justice, whose 19-year-old singer Maria McKee was heralded as the next Linda Ronstadt. Majer’s job was to help the band choose the right label, which they all agreed was Geffen. Courtside Lakers tickets for basketball nut Carlyne sealed the deal.

When Lone Justice came out in 1985, it received favorable reviews, but even produced by Jimmy Iovine, with a single- “Ways To Be Wicked”- written by Tom Petty and Mike Campbell, the album didn’t sell to either rock or country fans. But Majer had an idea for the band to find their audience in the fertile middle ground between rock and country that would become known as Americana. First she would make black-eyed peas and cornbread to bring to Willie on New Year’s Day 1986.

The good luck peas came with a favor request. “I told Willie, ‘I know you don’t usually have opening acts, but you’ve got a show coming up at in L.A. at the Universal Amphitheater, and I’m wondering if my new band can open.’ Willie agreed without ever hearing- or hearing of- Lone Justice. Producer Iovine and former UT student David Geffen (one semester in ‘61, the year before Janis) were excited to meet Willie Nelson backstage, and Lone Justice went over well, but Iovine ended up replacing Majer as manager by the end of the year. “They fired me after the L.A. Times ran an article (by Robert Hillburn) they didn’t like that I set up.” Fair’s in Dallas.

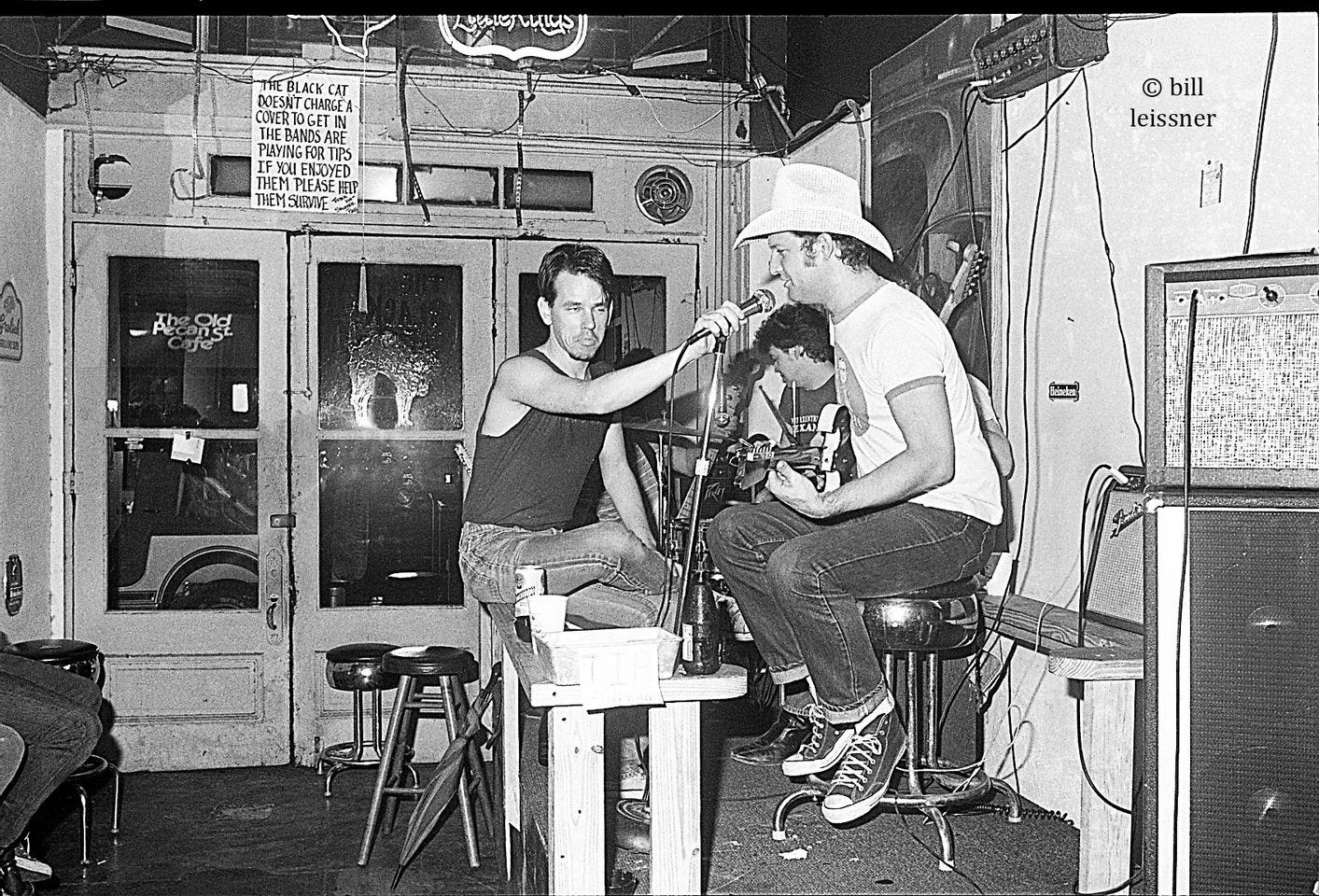

Well-connected management was rare in Austin in the ‘80s, with more acts trying to get Carlyne than the other way around. She had to say no to Lyle Lovett, but guitar wild man Evan Johns didn’t give Majer the option. “I went down and saw him at the Black Cat… and he kept introducing me as his new manager. We’d just met.”

Through Evan, she received a demo from a teenager with a big voice from the D.C. rockabilly scene. Kelly Willis and the Fireballs soon moved to Austin and signed with ATS.

Now retired, Majer says her calling card was creative development, preparing her acts for live performance and helping them pick the strongest material to record. Five songs on Kelly’s MCA debut came from Carlyne’s list. When Monte Warden put together the Wagoneers, Majer booked them at the Hole In the Wall for three months of woodshedding before graduating to the Continental and Liberty Lunch.

Carlyne’s mothering/managing instincts were honed at Soap Creek, which fostered a family environment amidst all the loud music, dope smoke and tequila shots. The Majewskis raised their own kids there, as well as those Sexton boys, Ian and Cheney Moore, and Doug Sahm’s kids. Who needs babysitters or summer camp? They all turned out pretty damn good

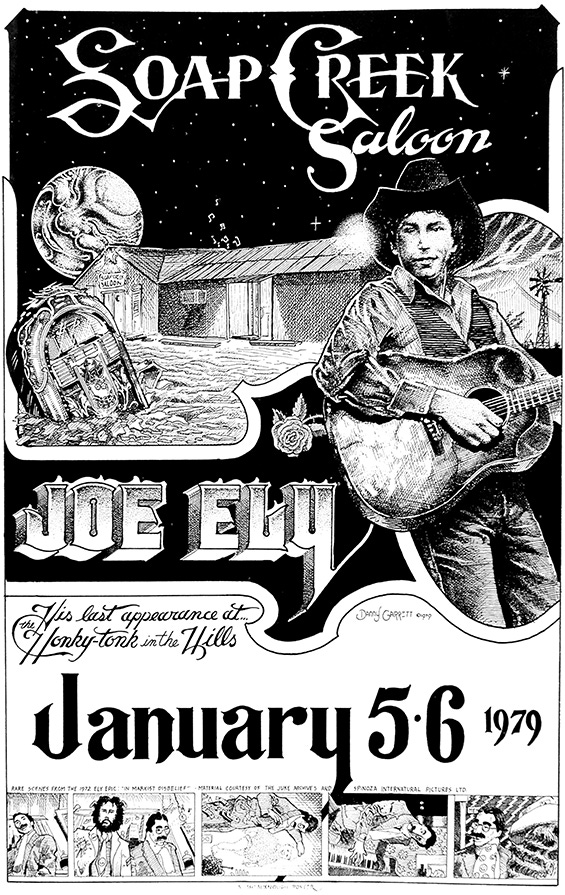

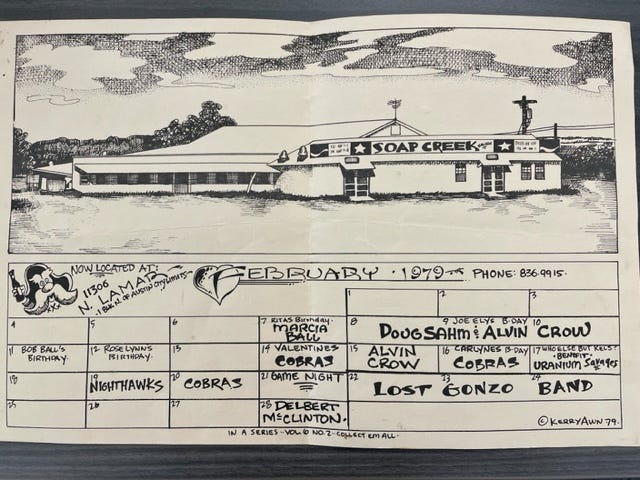

A condo project knocked Soap Creek #1 out of the Eanes school district in Jan. ‘79, but thanks to Townsend Miller, who introduced the Majewskis to Warren Stark, they found a new home at the old Skyline club at North Lamar. They signed the lease, at $1,000 a month, and opened in February 1979, but ruffled the Starks when two major motion pictures- Honeysuckle Rose and Roadie- filmed their nightclub scenes there. That was not in the lease! A subsequent rental agreement would stipulate that the Starks share in any Hollywood money.

The Skyline building was sold in April ‘81 to Jack Holford, a realtor and country music fan, and the Majewski’s were on the move again. In August 1982, Soap Creek moved into the former A.J.’s Backstage Bar, but George and Carlyne were burnt out by the 7-24-365 commitment that club ownership requires to do right. Their friend Ed Bennett from the old Split Rail took over Soap Creek #3 and ran it for two years until the lease ended, and Willie and Tim sold that block to a developer of high-end apartments. It’s where the younger cast members of Friday Night Lights stayed during filming (2006-2011).

After six years at NARAS, Carlyne went to work for SXSW in 2000, and for the next 17 years put out fires as the conference’s intermediary with the city government and public safety officials (official title: Chief Municipal Liaison). That’s about as behind the scenes as one can get- no news is good news- but Majer relished the role of helping the city and the conference work together in presenting Austin’s Super Bowl.

As club owner, manager, and executive, Carlyne Majer has greatly enriched the Austin music community. Willie must be proud.

Good piece about Carlyne—the biker chick who cut through the thick pot haze in A-town and got shit done. Her way was The Way.

I did not know of Carlyne's influence on the Texas music industry. Thank you again for sharing this important history! 💙📚🎶