Bluesman Frankie Lee Sims "put some rock 'n' roll money on it"

Before I'd ever heard of Lightnin' Hopkins I wanted him to sound more like Frankie Lee

He released only nine singles- on four labels- in his lifetime, but trust your ears when they tell you that Frankie Lee Sims is one of the all-time Texas blues greats, up there with Blind Lemon Jefferson, T-Bone Walker, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Albert Collins, Freddie King and Stevie Ray Vaughan. Listen as hard as he’s playing and the footnote becomes a big boot print on the march from rhythm & blues to guitar-driven rock.

When Jimmie Vaughan says “Frankie Lee Sims was his own universe” he’s talking about the Marshall native’s singular strut ‘n growl. “I never saw him live, so I’m not sure exactly how he did it,” Vaughan said, “but I’ve stole some of his licks.”

Frankie Lee’s self-contained cosmos could also reference a sensational talent who never really made it in this world.

Frankie Lee brought melody to the stomp, whipping himself into a rhythmic trance. “I put some rock and roll money on it,” is how he laid out his approach to the country blues. The dollars never came his way, though.

They say he liked his booze, which contributed, along with tongue cancer and pneumonia, to his death at age 53 in 1970. But Sims was sharp and forceful as a switchblade when it counted. His powerful voice was made to pierce juke joint smog and his grinding guitar attack didn’t know a false note.

While his “cousin” Lightnin’ was cashing big checks on the folk revival circuit, Sims and his drummer Jimmy “Mercy Baby” Mullins, were clearing out coffeehouses with their harsh, pounding blues.

“Frankie Lee was a little too primitive for the folkies,” says Dave Alvin, whose Blasters covered “What Would Lucy Mae Do?” (Alvin first heard the tune as a 12-year-old when he bought the budget compilation The Kings Sing the Blues at the corner store.) He gravitated to Sims and Lazy Lester of Louisiana when he started trying to write non-generic blues, he told Robert Wilonsky of the Dallas Observer, “because the structures of their songs were kind of free and countryish.”

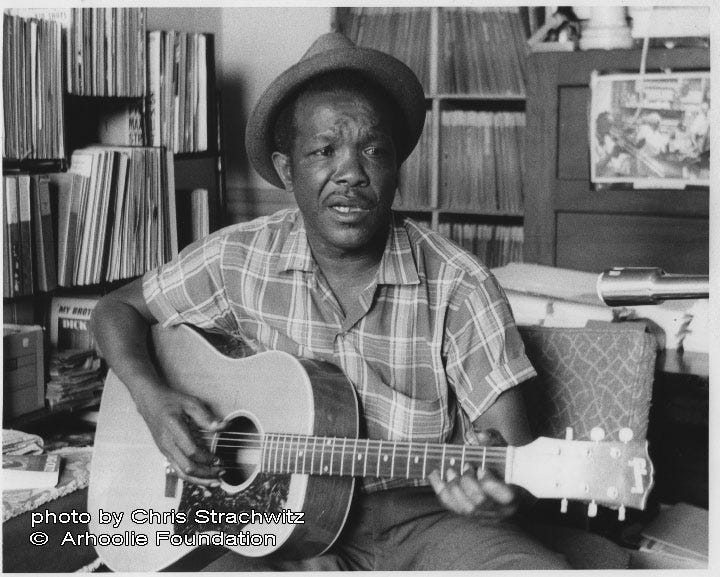

Not a fan was Chris Strachwitz of Arhoolie Records, who took the only known photos of both Sims and his kindred spirit Hop Wilson. “I feel both were very limited musicians and had not much energy nor charisma,” Strachwitz emailed back when I asked him about my two pandemic obsessions. All due respect to the legendary musicologist, but he’s as wrong as the critic who gave Powerage (the AC/DC album, not the sports drink) one star.

They say that if you remember the Sixties you weren’t there, but that decade completely forgot Frankie Lee Sims, who didn’t release a record in the last 12 years of his life. But he left his mark in the Fifties with recordings that hold up like the wheel. Noted Dallas producer Jim Beck, also a Marshall native, helmed his earliest sides on Specialty, including 1953’s “Lucy Mae Blues,” which became Frankie Lee’s signature tune by default. Known for producing career-making singles by country stars Lefty Frizzell, Ray Price and Marty Robbins, Beck’s credits rarely, if ever, mention Sims. But those blues romps are some of his best production work before Beck died young in 1956 from inhaling solvent while cleaning his equipment.

FLS made his recording debut backing his runnin’ buddy Smokey Hogg on guitar in 1947, then made two ‘78s under his own name for the same label, Herb Rippa’s Blue Bonnet. Like Frankie Lee, the label straddled country and blues, exemplified by his second single “Don’t Forget Me Baby”/ “Single Man Blues” which featured honky tonk steel guitar over Sims’s country blues pickin’!

Johnny Vincent, an Italian-American record man from Mississippi who had signed Sims to Specialty, took the singer as a parting gift to his new Ace label in Jackson, Miss. in 1957. Besides releasing four great singles on Ace and its Vin subsidiary, Sims backed his singing drummer on “Marked Deck,” which the Fabulous Thunderbirds covered on their 1979 debut LP. Jimmy “Mercy Baby” Mullins never heard that version, as he was shot to death in Dallas in 1977 at age 47.

Sims’s two years on Ace yielded righteously raggedy band takes on “Walking with Frankie” and “She Likes To Boogie Real Low,” but they didn’t sell like the label’s pop acts Jimmy Clanton (“Venus in Blue Jeans”) and Frankie Ford (“Sea Cruise”). Sims did appear on American Bandstand in 1957, playing guitar and singing backup for Jimmy McCracklin on “The Walk,” but never as the lead singer.

Frankie Lee recorded for the last time that we know of in 1960 in New York City for Bobby Robinson’s Fire label, but nothing from those sessions were released until 1985 when British revivalists Krazy Kat Records found the acetates and put out a vinyl-only LP. Lightnin’ Hopkins recorded the Mojo Hand album for Fire in New York the same month, with the same producer, so it’s likely Sims came up as a package deal.

“Like Lightnin’, most of his songs were in the key of E or A, but Frankie Lee had his own thing completely. He played wild,” says Vaughan. But Frankie Lee Sims also played loose with the facts of his life.

After moving to Oakland in 1963, where he got random gigs at the Club Savoy and Jabberwalk folk club, Sims sat down for a rare interview, conducted in Berkeley by Chris Strachwitz of Arhoolie Records. Sims reinvented a past in the way that the unjustly obscure are proficient at, plus more incentive to muddy it up was possibly due to him being investigated by the Dallas police over a shooting incident. Among Frankie Lee’s claims to Strachwitz: he was born in New Orleans on Feb. 29, 1906. He attended Wiley College in Marshall at age 12 and, after graduation, taught elementary school in Palestine, TX before joining the Marines during WWII. He was the oldest of 13 children and lone survivor. His father and Lightnin’ Hopkins mother were brother and sister. Oh, and that was Carl Perkins playing country steel guitar on Sims’ 1948 Blue Bonnet records debut!

Because 1906 was not a leap year, we know the first claim is untrue. And because his parents were East Texas sharecroppers, it’s unlikely they lived in New Orleans. The other claims are discounted due to common sense, like how would a 16-year-old Perkins come to Dallas from Tennessee and record with an instrument he’s not been known to play before or since? Sims also claimed to have played guitar on “Soul Twist” by King Curtis, but all evidence points to Billy Butler on that R&B instrumental classic. It does sound like Frankie Lee’s guitar on “The Monkey Shout” with Curtis on sax, so maybe Frankie Lee just name-dropped the more recognizable song.

According to his death certificate, Sims was born in Texas on April 30, 1917 and was never a member of the military. Searching ancestry.com shows no genetic link between Frankie Lee’s father Henry Sims and Lightnin’s mother Frances Washington, though, according to Mack McCormick, she did marry the half-uncle of singer Texas Alexander after Lightnin’s father Abe was murdered in 1915. Hopkins, Alexander and Sims have been said to be kin, but that designation seems more spiritual than biological.

Even before I knew Frankie Lee Sims existed, I wanted Lightnin’ Hopkins to sound more like him. The ultra-cool Lightnin,’ with his conk and shades and nickname, was always bubbling under, while Frankie Lee was over the top. Sam Hopkins was the consummate Texas country bluesman. But Frankie Lee Sims was somethin’ else.

I LOVE FRANKIE LEE SIMS. He was a bad ass, always playing the circuit jukes. The Krazy Kat tracks are a mere example of how he could get down and rip it up, but you can hear it's tempered because hopefully a single or two radio friendly could come out of those, but fact remains if he was in a live venue drinking and cigarette smog joint, the levels would be kerosene on a BBQ. Frankie ROCKED! Was prolific and just the samples of his phrasing and red hot poker tones burn bright on those hot mic'd Ace Label recordings. Definitely deserves mention as one of the great vocalists and guitar players, EVER! As John Lee Hooker says, "Natural Facts"!

I still like "Walking With Frankie" as his best song. Also, were the Ace records pressed in Dallas at A&R? I don't think Jackson, MS had a pressing plant, but I could be wrong. And check out Mercy Baby's, "One Room Country Shack." How Jimmie Vaughan and David Alvin discovered these guys is beyond me. They didn't carry these records in the stores I shopped at back in the 60s.