North to Shreveport: the Death of Johnny Horton

"Honky Tonk Man" was killed by a drunk driver on the way home from the Skyline Club in 1960

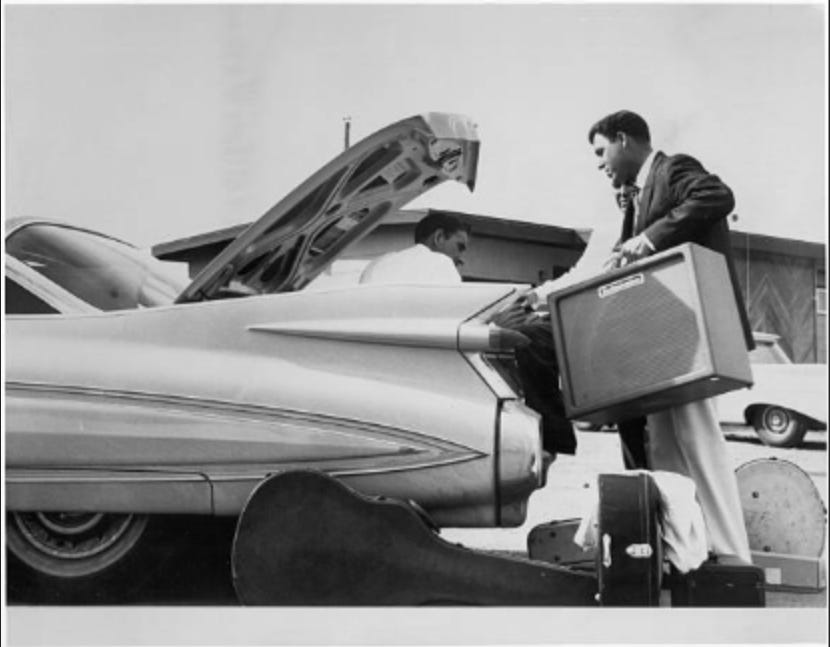

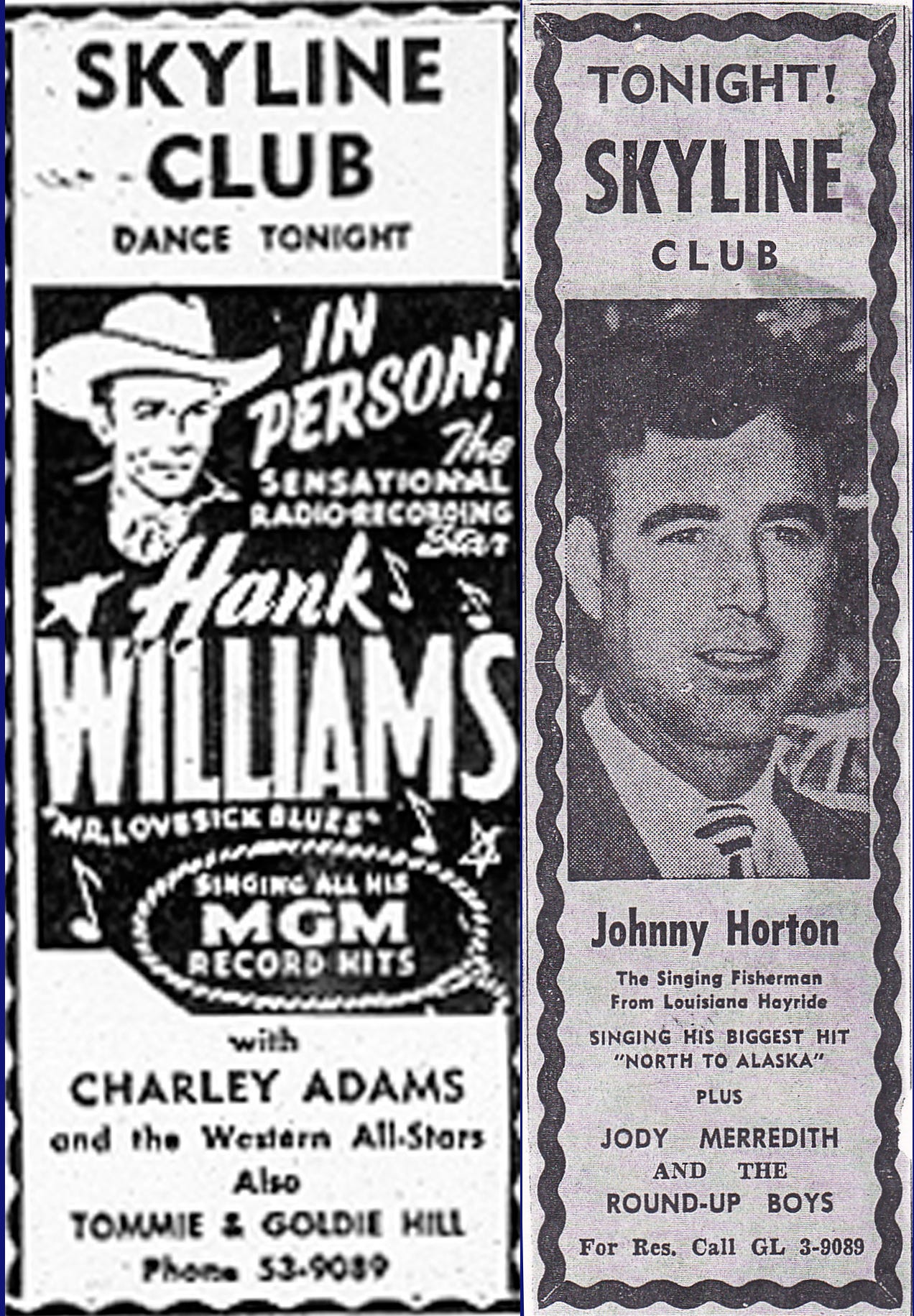

Fresh from a Grammy win for “The Battle of New Orleans” as the best country song, Johnny Horton thrilled a sellout crowd at the Skyline Club on Friday Nov. 4, 1960, then loaded his equipment into the trunk of his Cadillac, and took the wheel for the five and a half hour drive from Austin back home to Shreveport. Horton had plans to meet fellow country singer Claude King in the morning, the first day of duck-hunting season. He never made it.

On Hwy 79 in Milano, about an hour and a half northeast of Austin, Horton’s car was crossing a bridge over a railroad trestle when a Ford Ranchero pickup coming his way clipped the guardrail and careened into Horton’s car head on. The singer was pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital in Cameron at 1:45 a.m. He was 35. Passengers Tillman Franks, his bass-playing manager, and guitarist Gerald “Tommy” Tomlinson survived the accident, but were badly hurt, with Tomlinson requiring a leg amputation. The other driver, a drunk 19-year-old Texas A&M student named James Evan Davis, had only minor injuries.

Horton’s widow was the former Billie Jean Jones, who had been married to Hank Williams when his heart broke for the last time, in a Cadillac on New Year’s Day 1953. An eery coincidence, Hank’s final concert was also at the Skyline on the old Dallas Highway we now call North Lamar Boulevard.

While Hank’s Oct. 18, 1952 marriage to 19-year-old Billie Jean didn’t prevent a downward spiral of substance abuse, Horton was in a happy marriage, on a major career upswing, when tragedy struck. Alcohol contributed to the deaths of both country greats, but Johnny never touched the stuff.

Horton followed up “New Orleans,” the Jimmy Driftwood musical history lesson, which also topped the pop chart, with two more big hits in the “saga song” vein- “Sink the Bismarck” and posthumous No. 1 “North To Alaska.” It was all coming so easy after it had been so hard. Though he’d been recording since 1950, Horton didn’t have his first No. 1 hit, the Franks-penned “When It’s Springtime In Alaska (It’s Forty Below),” until 1959.

Horton grew up dirt poor, the son of sharecroppers who split time between Southern California, where Johnny was born in 1925, and East Texas, where he graduated from Gallatin High in 1944. After a couple tries at college, and a year prospecting for gold in Alaska, Horton moved to Los Angeles in 1949 and recorded for a couple of tiny labels- Cormac and Abbott. He also got a half-hour weekly TV show on KLAC in Pasadena called The Singing Fisherman. Horton was an avid outdoorsman since his boyhood in Cherokee County, Texas.

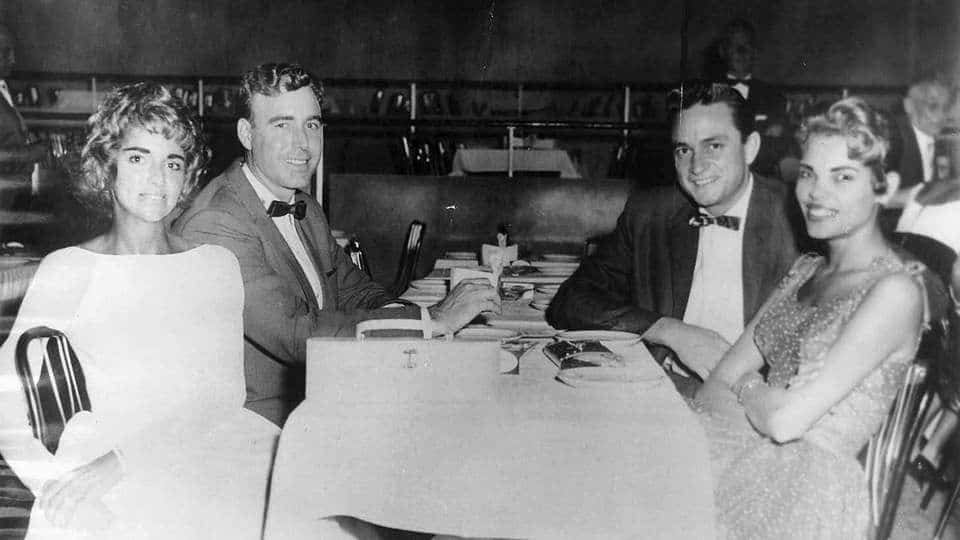

The Louisiana Hayride, where he appeared often, drew Horton and first wife Donna to Shreveport in ‘52. That’s where he met Hank and Billie Jean, the daughter of a Bossier City police officer. He also met Tillman Franks, who’d played bass with the Bailes Brothers on the very first Louisiana Hayride in April 1948, and managed Webb Pierce in the early ‘50s before he moved to Nashville and became a superstar.

Franks had his first great success managing Horton, who’d started off as a traditional country singer, backed by the Rowley Trio, consisting of guitarist Jerry Rowley, wife Evelyn on piano and sister Vera on guitar. After he saw and heard what Elvis Presley was doing on the Hayride, (broadcast nationally by flagship station KWKH), Horton switched to a more rockabilly style and had his first hit with “Honky Tonk Man” in 1956. (Such was Presley’s frenzied following, Hayride announcer Horace Logan had to repeatedly tell the audience “Elvis has left the building” so the rest of the program could continue, and a catchphrase was born!)

Horton married Billie Jean Williams in September 1953, nine months after Hank’s death. He was unknown at the time, so the couple lived off a $30,000 settlement from the Williams estate, and went about raising Billie Jean’s daughter from her first marriage to Harold Eshliman, to be joined by two daughters of their own.

After the deaths of her country singing husbands, Billie Jean made a couple records that went nowhere, then fiercely fought for her name and the money that would help her raise three kids, aged 10, 5 and 2 at the time of Horton’s death. (Billie Jean was just 28.) She won a million dollar lawsuit in 1971 against MGM and the biopic Your Cheatin’ Heart, which portrayed her as a grifter and a harlot, never legally married to Hank. Then she went after half of Williams’ publishing and won a three-year legal battle in 1975 against attorneys representing Hank Williams Jr. Though she’d signed away the rights to Hank Williams’ songs in 1953, Billie Jean was entitled to receive royalties after the copyrights were automatically renewed in 1972. The court victory brought an estimated $250,000 a year to Billie Jean Horton Enterprises.

Don’t mess with the protective Billy Jean, who didn’t just fight for money. In 1981, she flew from Shreveport to Spokane, Wash. to confront a singer claiming to be Johnny Horton Jr. All she got was an apology from the imposter and a promise to never do it again. But that’s all she wanted.

Several years after Horton’s death, Billie Jean remarried an insurance man named Kent Berlin, but keeps the Horton name for her business. She just turned 90 in the Shreveport nursing home where she lives.

Somehow, Johnny Horton, who brought country music to the top of the Billboard Top 40 in 1959, and gave Dwight Yoakam his breakout hit in 1986, is not in the Country Music Hall of Fame. That should be rectified. Horton is buried at Hill Crest Memorial Park, in Haughton, just east of Shreveport.

The year after the drunk-driving accident, James Evan Davis was found guilty of murder without malice and received just two years probation. He lived to be 65.

The bridge in Milano where the fatality occurred has been paved over and widened to four lanes. About 500 feet east of the crash site is a modest memorial next to the volunteer fire department. It’s not even attached to anything. Someone could put it in the trunk of their car and just drive away, but how could that not bring bad luck?

I really enjoyed this article, Michael! I was just a kid in Cameron, Texas, only twelve miles from Milano, when Johnny Horton was killed. I remember being in a crowd of onlookers, at the auto wrecker's yard, gawking awkwardly (and somewhat morbidly?) at the demolished Cadillac. My mother reached into the sprung open trunk and grabbed a postcard. It featured Horton, all done up in quasi-War of 1812 garb, I suppose, promoting "the Battle of New Orleans", I guess. The card had a single, round drop of dark red "something" on one side...probably just errant ink from printing but you know how a kid's imagination goes. Horton's tale had a sad and eerie ending.

Billy Jean often ordered pizzas from where I worked at Johnny’s pizza in Shreve Island area. Whenever she’d order I would get so excited. I tried to explain to my co-workers who she was. But, they just looked blankly at me. I always told the drivers to be very nice to her.