East Side Stories: Smokey Rhodes played piano with his feet

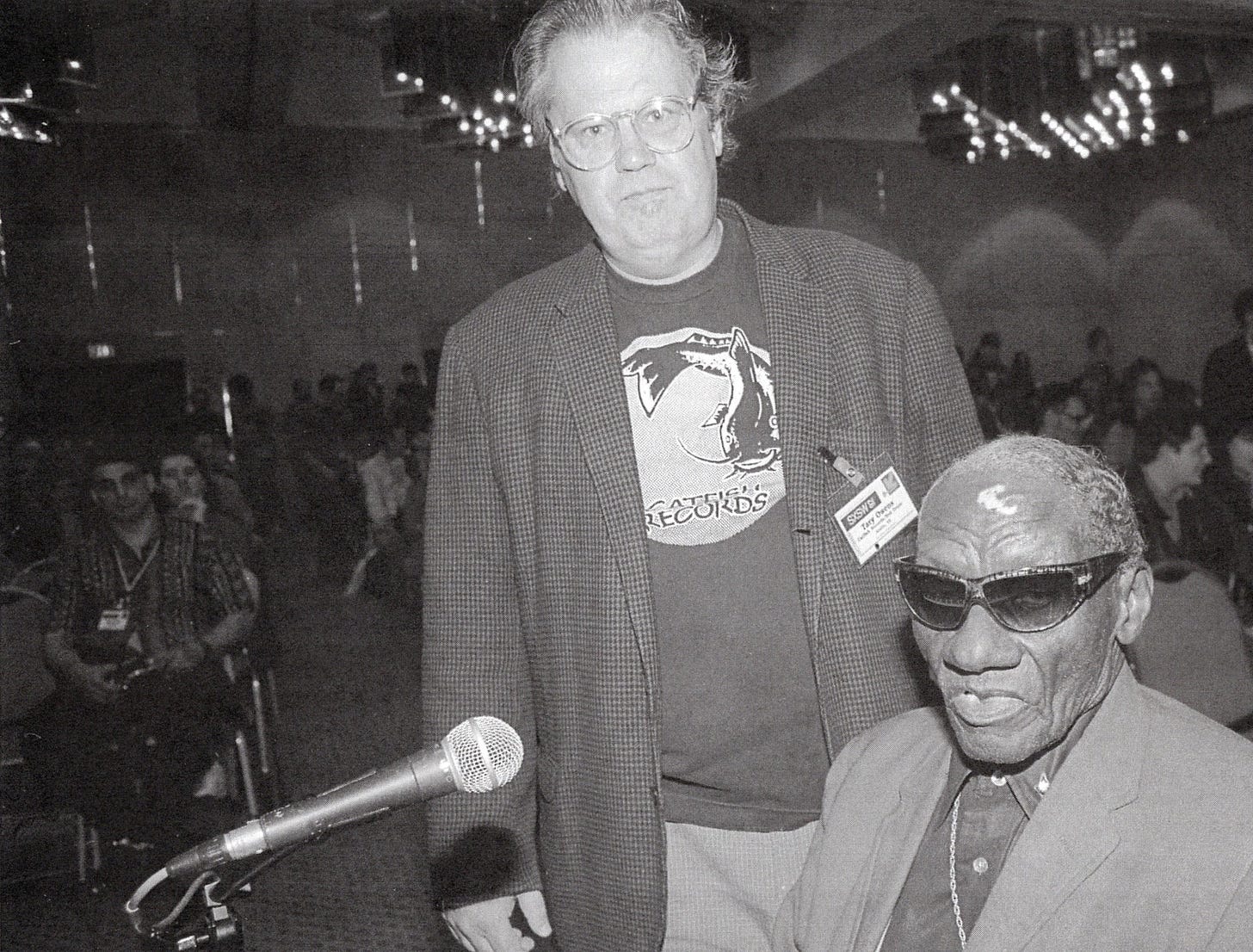

Tary Owens created a late '80s revival of East Austin bluesmen with his Catfish label

At age eighty-two (or eighty-three—he wasn’t sure) in 2002, Oscar “Smokey” Rhodes still had the moves that made him the favorite dancer of Austin musicians, including Stevie Ray Vaughan, who would often call him onstage. As one of the last of the great buck dancers (from “a buck and a wing”), Rhodes was often sought out by up-and-coming hoofers.

Visiting Rhodes on an afternoon at his apartment in the Rosewood Courts housing project in 2002 was to hear about a life that knew great camaraderie, but also tragedy. The highs and lows were reconciled in the marriage of clicks and thumps of the flat-footed buck dance, which is more syncopated and reliant on musical accompaniment than the standard tap dancing. When Smokey was dancing, he said, his mind was at peace.

This craft was handed down by his mother Mary, a rare female buck dancer, who toured the Southern vaudeville circuit in the 1920s and 1930s. She also taught Smokey how to dance tap and the ol’ soft shoe.

“I’ve missed my mother every single day since she passed,” he said of the fun-loving disciplinarian who died of heart failure in the early ’70s. “She taught me that when it’s time to work, you work your tail to the bone. When it was time to play, well, go have yourself a ball.”

Mary and Harvey Rhodes, moved their family from Bastrop to East Austin in 1938, when Harvey got a job at a cotton gin on East Sixth where the post office eventually was built. “They’d dance for a man from Kyle who sold a potion he called ‘Getcha Ready.’ Wasn’t nothing but hackberry limbs all chopped up and boiled. My parents’ job was to rouse up a crowd with their dancing, then the medicine man would step up and sell his bottles.” Smokey and his brother Willie would sometimes play percussion. Willie died of pneumonia at age 13, another loss Smokey said he never got over.

Before he started taking dance seriously, Rhodes’ first love was baseball. After attending Anderson High School, Smokey was a star left fielder for the Austin Black Senators, a minor league Negro League team that once featured future Hall-of-Famer Willie Wells. Calling the games at Disch Field was Smokey’s best friend Lavada Durst.

Local 7-Up distributor Ed Knable was a big baseball fan who often gave jobs to players he liked, so he hired Smokey as a driver—a job he’d hold, during three different stints, for thirty-one years.

The first time he had to quit was when he was drafted into the Navy. Back in Texas after the war, Rhodes delivered ice for a Waco company. One stop on his route was the Harlem Club in Dallas, ruled by blues guitar pioneer T-Bone Walker. “He blew everybody away,” Rhodes said with a big smile. “I got so excited I just hopped onstage and started dancing. That’s how it started for me, dancing with bands.”

Smokey especially liked to dance to the rhythms of barrelhouse piano, and in East Austin in the ‘50s and early ‘60s he teamed with such ivory thumpers as Robert “Fud” Shaw, Roosevelt “Grey Ghost” Williams, Erbie Bowser, and Lavada Durst. “The piano, man, that’s the whole program with buck dancing,” he said. “It’s like playin’ piano with your feet.”

When there wasn’t a piano around, Durst would pound out rhythms on a barrel while Rhodes danced. In their teens, the pair used to do this routine for tips from a raft in Barton Springs Pool. “They used to have this contest, where four guys would stand on the raft with one hand tied around their back and the other one with a boxing glove on it. They’d try to knock each other into the water and the winner would get five bucks. Well, when they were all done with that, me and Lavada would take over the raft.” Barton Springs was segregated, but that was loosely enforced unless Blacks wanted to get in the water. The Pool was desegregated in 1960 after a series of “swim-ins.” Google “Joan Means Khabele.”

Lavada Durst became the first Black radio deejay in Texas in 1948 when future governor John Connally, after hearing him call a Black Senators game, hired him to play R&B on KVET as “Dr. Hepcat.” His “Rosewood Ramble” show was popular with white kids at UT and hip townies, a tradition that would continue with Bill Bentley’s Twine Time show on KUT, inherited by Paul Ray, and passed on to Mike Buck. Kids in Austin have had free access to hardcore blues for 75 years. It should be noted that Elmer Akins, the father of AISD’s first Black principal Charles Akins, was heard on KVET before Durst, but he bought the time for his 15-minute gospel show for the first couple years. Gospel Train ran Sunday mornings on KVET from 1947 until Akins’ passing in ‘98.

By the mid-‘60s the Eastside barrelhouse scene had died down, with Dr. Hepcat becoming a preacher, the Ghost driving a school bus, and Smokey with his ice route. But then, out of nowhere, Fud Shaw was becoming in demand as a live performer at age 54. He was tracked down in 1963 by Fourth Ward piano obsessive Mack McCormick, who recorded Texas Barrelhouse Piano for his Almanac label that year in Austin. There was a true kinship between the hippies/folkies and the blues originators, and soon Shaw was making more money playing music than he was running Shaw Food Market on Manor Road. Shaw made the most of his second chance, performing on a double bill with Janis Joplin at the Texas Union Ballroom in May 1966, her last local gig before moving to San Francisco to sing for Big Brother and the Holding Company. Shaw played the Kerrville Folk Festival in its first fourteen years before a heart attack took him away in 1985 at age seventy-six.

An unlikely revival for the rest of the East Side piano gang would come in the late ‘80s, when Tary Owens and Jon Foose of Catfish Records got the lifelong friends back in the studio, and on tour as the Texas Piano Professors, featuring Rhodes as a dancer. Smokey’s “Stop Time” routine with Bowser, was a nightly crowd-pleaser.

A protege of noted UT folklorist Americo Paredes, the Port Arthur-raised Owens had recorded the Grey Ghost in 1965, but spent the next two decades in a fog of his own doing. One day, after getting sober in the mid-‘80s, he heard his old Ghost recordings at a blues history exhibit at UT and set out to find the last of the original barrelhouse players. Owens worked as a drug counselor who often talked to inmates, usually ending a session by asking if any of the men had ever heard of an East Austin stride piano player they called the Grey Ghost.

Otis Bell’s hand shot up. “Hell, I knew the Grey Ghost,” said Bell, who was awaiting trial for murder. “He was out of his damn mind! So I called my grandma and she said he was still alive, still living on Juniper Street. The next week I told the drug counselor where to find him.”

Thanks to his prison informant, Owens got with an 84-year-old Ghost, and reissued the 1965 tapes on Catfish in 1987, as well as an album of new Ghost recordings a few years later. In 1991, Owens and Foose put out It’s About Time by T.D. Bell and Erbie Bowzer, that took them from the Victory Grill to Carnegie Hall.

“Those guys were my brothers,” Smokey stated in 2002. “Lavada Durst, Grey Ghost, Erbie Bowser, T.D. Bell — man, we were all so tight.” As he sat in the living room with the front door open on a hot afternoon, sadness passed over his face.

“They all died in a row. Like, one died on a Saturday and here comes Tuesday and another one passed. Now all my friends are gone.”

Durst died in ’95, with Grey Ghost and Bowser going the next year. Bell passed away in 1999. Smokey Rhodes was the last to go, dying of cancer in 2004, at age eighty-four (or eighty-five). To the very end, he honored his mother in the steps she taught him, and his friends in the moves their music inspired.

When drummer Dwight Dow and I left the Fabulous Chevelle's to for the Sweetarts in 1965, the initial keyboardist and guitarist were Erbie Bowser and a guy whose name escapes me. "Half Black, Half White: You Gotta Hear 'Em, They've Outta Sight!! So PC! Not.

Thank you for an amazing history lesson Michael