Post-War Austin scene thrived on the G.I. Bill

Dolores, the Skyline, the Victory Grill and the birth of KVET

After the end of WWII, roughly half of the 15,118 student body at UT attended on the GI Bill. They were older, of drinking age, and had money. It was the first heyday of Austin nightlife, though most of the music venues were far away from the university and downtown.

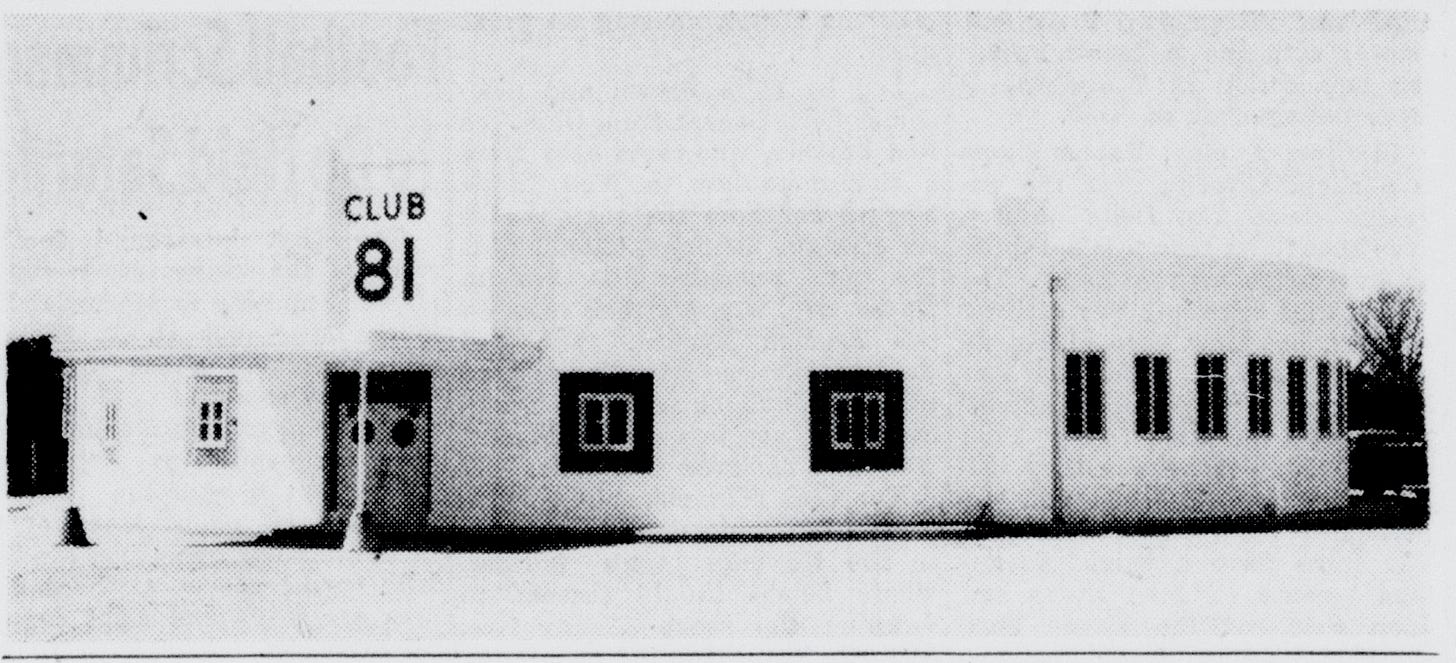

A pair of war vets, R.D. Edwards and Joe Sanders, opened the swanky Club 81 on the San Antonio Highway (4700 S. Congress today) in March 1946, booking big bands of R&B (Jimmy Liggins, Johnnie Simmons) and Western swing. The Statesman called it “the costliest club ever built here,” but less than two years later it burned to the ground. Another Club 81 opened several blocks south in 1955, but it wasn’t affiliated. South Congress was US 81.

In the nine years before the big bang of rock ‘n’ roll, the local music scene was dominated by Western Swing and country bands including Jesse James and All the Boys, Doug and the Falstaff Swing Boys, Leon Hawkins and His Buckaroos, Hub Sutter and the Hub Cats, and Buck Roberts and the Rhythmaires (featuring Johnny Gimble). The Taylor-based Jimmy Heap and the Melody Masters recorded nascent versions of the classics “Wild Side of Life” and “Release Me,” later made more famous by Hank Thompson and Ray Price, respectively.

But Dolores and the Blue Bonnet Boys stood out because it was that rare country band led by a woman who wasn’t the main vocalist. Far from a novelty, Dolores Fariss wrote songs, chose outside material, played piano and ruled her group of talented musicians like Bob Wills in a skirt.

Rule No. 1 was no drinking before or during a set. And Fariss was also clear that she didn’t like her musicians showing off. “Dolores was very commercial-minded, and she called the shots as to what we played,” said the band’s fiddler, Bill Dessens, who joined the Blue Bonnet Boys in 1949 while still in college in San Marcos. “Her motto was ‘Keep it simple, boys.’ She’d say that whenever me and (twin fiddler) Joe Castle would take off on a crazy course. We used to get together in the basement of Joe’s church and learn songs like ‘Stompin’ at the Savoy,’ but Dolores didn’t care for that hokum (jazz).”

The band had a big fan in Kenneth Threadgill, who often sat in at the Skyline. “Dolores and the Bluebonnet Boys did more to teach me about music than anybody I’ve ever known,” he told the Statesman in 1970.

Rather than tour the dancehalls and VFW halls all over Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana, Dolores and the Boys rarely ventured outside Austin, where they played an average of three nights a week at the Skyline. The group also performed at Dessau Hall twice a month and the Buckholts SPJST Lodge in Milam County about four times a year. They knew how to make the people dance, throwing in a couple polka numbers each set.

There was more money out on the road, but the Blue Bonnet Boys stuck to Austin and environs because drummer Lee Fariss, Dolores’s husband, had a successful home construction business with his wife’s father, Alfred Hanson. They also had two young sons- James and Don.

Of Danish descent, the Hansons came from Hutto, where Alfred had a polka band featuring teenage daughter Dolores on piano. Lee Fariss also had a band at the time, Lee’s Bees, in which drummer Fariss was the only member who wasn’t blind. Lee and Dolores met at a Hansons polka gig in 1930 and married the next year.

The group publicized its shows by playing live on KVET (AM 1300), which signed on the air Oct. 1, 1946, the same year Dolores put together her Blue Bonnet Boys. Before KVET, there were two radio stations in town – the Lady Bird Johnson-owned KTBC (AM 590), a CBS affiliate, and ABC-aligned KNOW (AM 1400), headquartered in Norwood Tower. KTBC featured Jesse James and His Boys every day at 1 p.m. Dolores was KVET’s answer.

Lyndon Johnson, then a rookie U.S. congressman, encouraged several of his closest associates, including future Texas Gov. John Connally and future U.S. Rep. Jake Pickle, to pool their resources and launch a third station, before NBC could enter the market. Better that competitors be friends than enemies. Because the new station owners and 10 investors ($5,000 each) were all veterans of World War II, they went with the KVET call letters.

In 1948, KVET expanded its market by hiring African American DJ Lavada Durst, and Lalo Campos to host Spanish-language music shows every day. Those popular programs-Rosewood Ramble and Noche de Fiesta, respectively, kept the local music scene from being lily white.

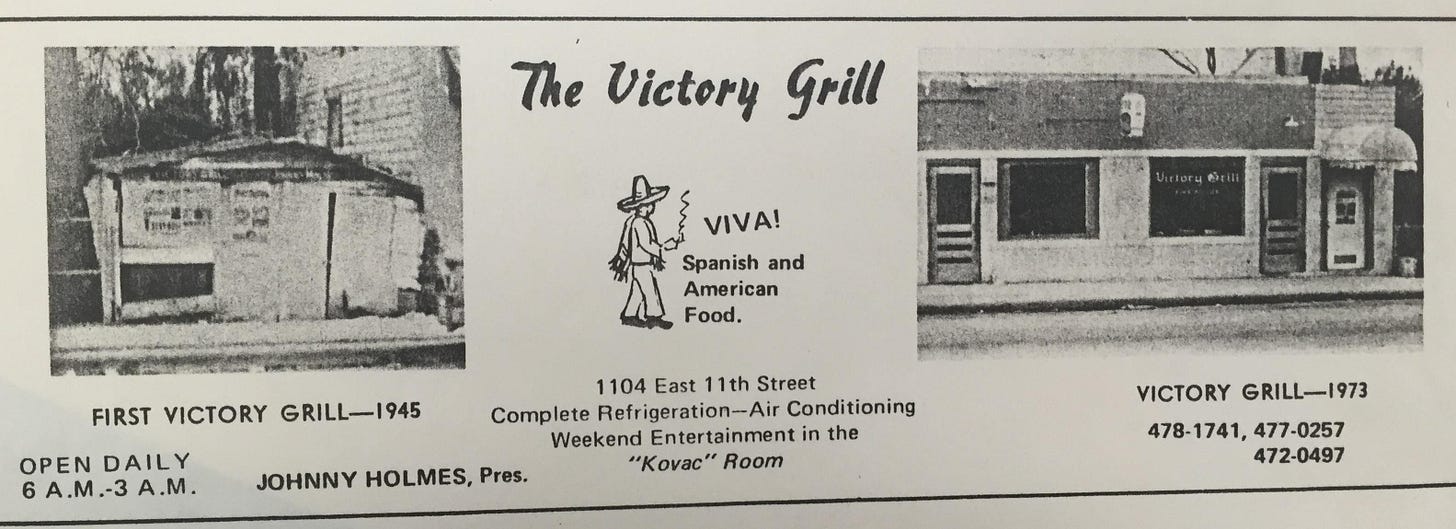

Over on the Eastside, during that time of segregation, the Victory Grill- which opened in August 1945, the day after the Japanese surrender- was a safe haven for Blacks to also celebrate the end of WWII. Originally a small icehouse and burger stand, the V.G., owned by Bastrop-raised Samuel Huston College graduate Johnny Holmes, moved a block west in 1947, to the current building at 1104 E. 11th St. The new Victory was a classy diner, with waitresses in starched maroon shirts, but when Holmes added the Kovac Room (named after a club in Alaska from his travels) in 1951, he created a near-perfect nightclub in the back. With a nice stage and dancefloor, café-styled booths and a bar of glass bricks with red, green and blues lights shining through, this 350-capacity stop on the “chitlin circuit” between Houston and San Antonio drew such acts as B.B. King, Ike & Tina Turner and Joe Tex before they became mainstream attractions. They usually stayed at the Deluxe Hotel at 1101 Navasota, the only Austin hotel for Blacks, or at private homes.

The Grill also spawned a local blues scene that included Erbie Bowser and T.D. Bell, the Grey Ghost, Jean and the Rollettes, Major Burkes, Blues Boy Hubbard and more. A singing soldier from Fort Hood named Bobby Bland, came down every weekend in the early ‘50s to take top prize in the talent show.

East 11th Street, with Tony Von’s Show Bar on the next block from the Victory, and Shorty’s jazz club across the street, was The Stroll on the Eastside in the late ‘40s/ early ‘50s. That Shorty’s faced away from the sun in the afternoon, and had an awning for rain, made it where the prostitutes hung out. At night the strip lit up like someone dropped two blocks of Harlem in the middle of Texas. The Victory Grill and Charlie’s Playhouse (which took over the Show Bar location) fought it out to be Austin’s Apollo, and Charlie’s won when it stole Blues Boy Hubbard and the Jets by paying $12 a man instead of the $10 they were making with Holmes. When it came to food, the Victory got heavy competition from Southern Dinett, a soul food joint that opened a block away in 1947.

Lining up talent was his favorite part of the job, while the restaurant business was just wearing him down, so after the Victory Grill had been open only seven years, Holmes moved to West Texas. His best musician friend B.B. King had bemoaned that there was no place to play between San Antonio and El Paso, eight hours away, so Holmes opened the Cobra in Big Spring, which held 1,100 people, then expanded to Odessa.

He retained ownership of the VG, however, and returned in 1965, with Mary Wadsworth closing her club, “Big Mary’s” at 1808 E. 12th Street, to run the Grill. Richard Powell opened Good Daddy’s in the old Mary’s spot, and with Sam’s Showcase in the former Tasby’s Tavern just a block west, 12th and Chicon rivaled 11th Street for live music. Sam Campbell continued one of the Tasby’s popular weekly attractions- a cross-dressers revue called “Women of Tomorrow” on Tuesday nights.

Tough times in the ‘70s closed the Kovac Room first, then the cafe. The Grill sat boarded up for years, but through the efforts of Tary Owens of Catfish Records and others, the club reopened with Holmes in charge in 1987. It had one good year, then a gutting fire. The ailing building was marked for the bulldozer in 1990, until Black community leaders stood up for East Austin history. Holmes family friends R.V. Adams and Eva Lindsey did their best to keep the Grill afloat.

Aged 83 and suffering from Alzheimer’s, Johnny Holmes died of hypothermia in February 2001, when his daughter found him in his driveway. His family still owns the Victory Grill, which was included on the National Register of Historic Places in 1998.

Excellent, I love reading all this Austin/Texas music history, Michael, appreciate it!

That was a fantastic and informative article. An excellent slice of Austin musical history.