Return to the Scene that was Mine

Statesman music critic job brought me back for a bumpy ride in 1995

I came back to Austin in 1995 B.C. (before cellphones) to take the pop music critic job at the Statesman. I was coming down from the Dallas Morning News, and not just geographically. The DMN was the biggest, most prestigious paper in Texas, having just bought out the Dallas Times-Herald. But I wanted to be in Austin, where music grew wild, and meant more than cheerleaders and Neiman-Marcus. And there was none of that courtesy title nonsense (“Mr. Loaf performed all but one song from Bat Outta Hell”).

When the news broke that I was coming home, I got an irate call from Louis Black, who said I was too stupid to see that the Statesman was using me to try and put the Chronicle, the paper that gave me my start, out of business. Oh, that was exactly what I saw, but I knew, with all that SXSW money, the Chron wasn’t going anywhere. The alternative paper thrived when I worked for the competition.

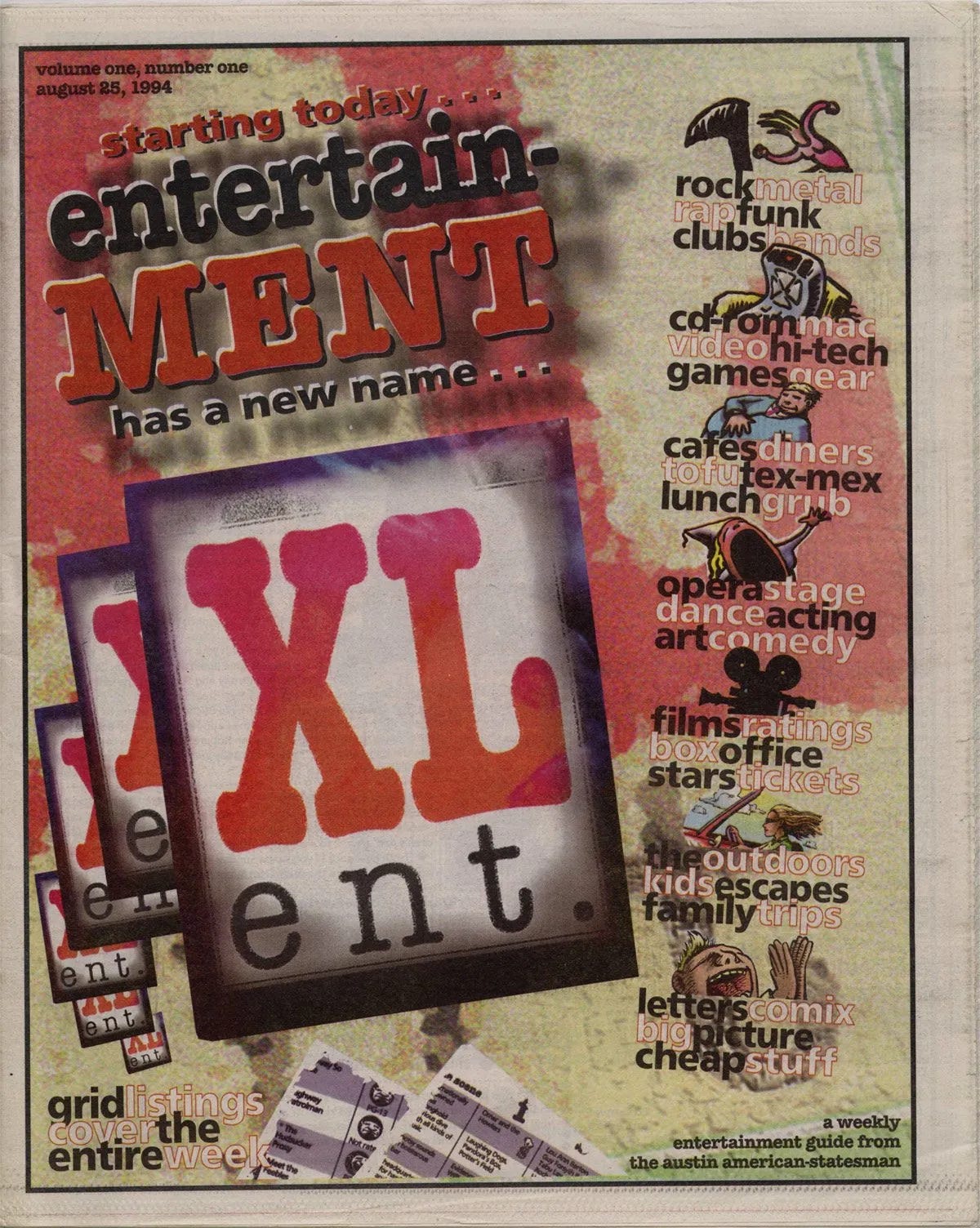

I was hired, pending a drug test I’d been studying for, to turn around the Statesman’s weekly entertainment supplement XL ent, which was going to be distributed free citywide, right next to the Chronicle. Interim editor Terri Burke said XL was kind of a joke around town- the Staidsman trying too hard to look hip- and I would be the high tide that raises all boats.

The problem was that the XL staff thought they were kicking ass. None of them really had any experience in putting together an entertainment publication, so they were understandably jazzed to see their copy editor dreams come true. It was actually not bad, if a tad too cartoony. But then Mr. High Tide shows up to raise all the flotsam and jetsam.

My first feature was a 3,000-word essay on Michael Jackson in advance of the HIStory boxed set. I spent about four days at home penning that masterpiece, and everybody at my new job thought I was goofing off. Especially since I came in late afternoon wearing Jiffies, the corduroy house slippers favored by old blues musicians.

On my first day in the office- June 6, 1995- I got word that Sims Ellison, the beloved bassist for hair metal band Pariah, had committed suicide. He was good-looking, talented and had a supportive family, but his band was his life, and their farewell show at the Back Room was also his. Everybody thinks musicians have a charmed existence, but band breakups can be as traumatic as a divorce.

An employee assistance program had helped me with my marriage breakup, and I wondered in a column (below) if such a program could be created for the unique mental upkeep needs of Austin musicians. Suggesting the SIMS Foundation was my greatest achievement as an Austin writer, but to my editors it just proved that I needed to be in the office more. Why write in peace at home, in a cloud of stimulating marijuana smoke, when you could sit in a big room full of yammering yentas? I’m pretty sure the white noise application was invented by someone whose desk was near the sports department.

Once I missed a weekly XL meeting to finish a Selena appreciation, and as punishment I was assigned Aquafest, a glorified county fair, while a freelancer got the plum Lollapalooza cover story. That would’ve never flown at the Morning News, where a critic’s beat was sacred and defined. I got called into the office once for trying to pawn a Billy Joel concert off on a freelancer. And heaven help you if a AP obit on someone in your coverage area ran on the front page.

I attended college for only a year, but three years at the DMN earned a degree that I was eager to put in use in Austin. But tact is something I wasn’t taught.

Cluelessness is a diva trait, so I’m not totally sure how much of a jerk I was when I arrived, but going by the pushback from colleagues I must’ve been unbearable. But I didn’t care. I wasn’t there to make friends or bide my time. A perfect day at the Statesman was one where the phone rings only once, to ask what you want to do about dinner. But I wanted to stir things up.

There was a complaint that I intimidated the copy desk, towering over them with concerns about perfect headlines, changed. “You should squat down to their eye level when you address them,” I was advised. What is this, Mister Rogers’ Fucking Neighborhood? But that was actually a really good suggestion. Looking back, they really tried to make it work, but then my salary became known in the newsroom, and I was the asshole again.

Amid the territorial pissings, the XL founders established guidelines to keep me in place. Basically, I was a writer/reporter, and they were in charge of editing and design. I was the rancher and had no say in how the steaks were cooked. Meanwhile, I lost an ally when Burke didn’t get the editor-in-chief job, which went to Rich Oppel, a Pulitzer Prize-winning editor from the Charlotte Observer.

After four months at the Statesman I quit. I got into it with an editor one day, when he ordered me to clear my slate (including an interview with red hot Alanis Morrissette) to report on a controversial music festival in August ‘95. “You haven’t shown me anything as a reporter!” he shouted. I’d been at the Statesman for two months.

Promoter French Smith of the wildly successful Pecan Street Festival put a fence around five blocks of Sixth Street and charged $5 admission for his Robert Cray-headlined Sixth Street Music & Heritage Festival. The uproar from restaurants and clubs was instant, as their customers had to pay cover, too. Was it even legal to charge money for access to a public street? XL was the event’s media sponsor, and we had to ramp up reporting to save face.

“So I don’t have to do the interview?” Ms. Morrisette said, when she called at the scheduled time and I told her she oughta know that the story was off. “Great!” Touring musicians hate phone interviews even more than they do 6 a.m. wake-up calls.

I did get a pretty good story out of the Sixth Street mess, which led to Smith’s resignation as chair of the Austin Music Commission. But the Statesman didn’t get that scoop. The copy desk held up the story because it had only one source- French Smith- and the Chronicle beat us.

But that was fine. They were going to be my new employer. The afternoon I had the big newsroom dustup, I drove right over to Louis Black’s office and worked out a deal to produce a writerly column every other week, rotating with Michael Ventura’s “Letters at 3 a.m.” Then I lined up a freelance contract with the Dallas Observer. Both gigs would bring me only $2,400 a month, but I was moving back to Big D to be closer to my 15-month-old son. It was stupid to leave my job at the Morning News, who were still pissed off.

Before I left I was taken to lunch at Guero’s by Statesman publisher Roger Kintzel, and we talked about what it would take for me to stay. The answer, which I kept to myself, was health insurance. Neither the Chronicle nor the Observer offered coverage.

The plan I worked out with Oppel was to continue to be on the Statesman staff, at 75% salary, while living in Dallas for six months. Then I’d have to either move back to Austin or quit the job. I think I was the first person ever to live in Dallas and work in Austin.

I had a Sunday night radio show (“Critical Mass”) with McLeese on 101-X, so I drove down for that, usually reviewing a show in town the night before. But I was mumbling, stumbling wreck on the radio, and it was a long drive for $125 a week. I quit before I was fired, replaced by Andy Langer’s “Next Big Thing,” which worked out best for everyone. I don’t like to do things I’m not good at, which some of my exes would refute.

The column I was going to write for the Chronicle, I wrote for the Statesman and won a Headliner’s Award.

I did move back to Austin after six months, giving my relocation allowance to the ex-wife so the family could all live in the same city. And things improved drastically for me at the Statesman, as my tormentors became trusted colleagues, and I became less of a butthair. But by 1998 I was getting burned out as a music critic.

COMING Part II: Becoming Austin’s Walter Winchell with “Inside/Out”.

Great stuff Corky. Thanks for being honest.

God, I miss journalism.