Roky's Return to the River of Golden Dreams

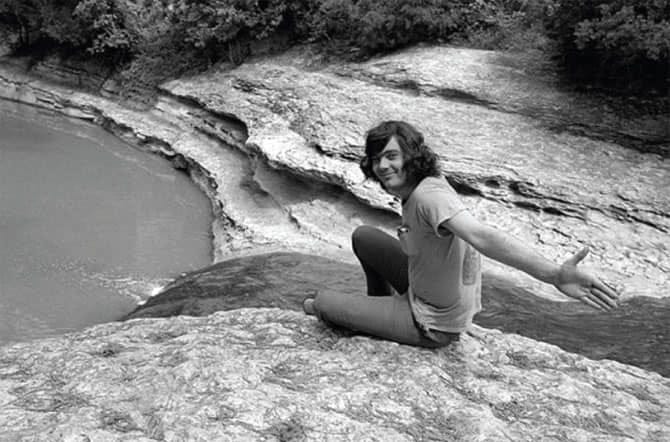

Remembering the greatest musician Austin's ever produced on the 75th anniversary of his birth

A rafter-shaking chant of "Raw-Key! Raw-Key! Raw-Key! Raw-Key!" with an ocean of overhead hands clapping in rhythm. Walking onstage at the Hultsfred Festival in June 2007 was psychedelic rock pioneer Roky Erickson, who just six years earlier was in such a state of mental and physical dishevelment that it seemed unlikely he'd ever play another show.

But when Erickson and his band opened the Swedish set with "Cold Night for Alligators" - Erickson's voice confident and shimmering, his guitar-playing forceful and instinctive - it became sensationally apparent that this wasn't going to be a freak show, but a stunning resurrection.

When the set ended a euphoric hour later with a powerful version of the 1966 cult classic "You're Gonna Miss Me," the former 13th Floor Elevators frontman reviving the banshee wail that turned Janis Joplin into a rocker, the crowd demanded an encore with such intensity that if it hadn't gotten one, there probably would have been a riot.

The comeback of Roger Kynard Erickson ("Roky," pronounced "Rocky," combines the first two letters of his first and middle names) was the most improbable in the history of rock 'n' roll, as if Syd Barrett had rejoined Pink Floyd and stole the show.

Offstage, the man credited with inventing "acid rock" with the Elevators in the ‘60s was blowing minds by doing everyday things like driving a Volvo and exercising his right to vote. “It’s really a miracle,” said younger brother Sumner Erickson, who was awarded legal guardianship of Roky from their mother in 2001. Evelyn Erickson was an unorthodox caregiver, who supported her oldest child’s decision to not take his meds, even though it meant he sometimes had to sit between walls of white noise to quiet the voices in his head. Evelyn did not want to numb her gifted child.

Roky’s recovery started with medication and therapy and a move out of the section 8 housing, where he lived like a hermit except for daily visits from his mother. Sumner took him up to his home in Pittsburgh for a year and when Roky came back down to Austin he had new teeth and a smile, though he clearly still had mental issues.

For decades, Erickson wouldn’t let anyone touch him, but on recent tours of Europe and North America, he hugged fans back, signed autographs and posed for photos after shows. But it’s not like Roky could appear on a talk show. His words and thoughts don’t follow usual patterns.

“Where Roky’s concerned, ‘normal’ is just a setting on a washing machine,” said tour manager Troy Campbell. “He just comes out of left field sometimes, like the other day we had pizza and I asked if he’d had enough to eat and he said ‘I’m full as a ghoul.’”

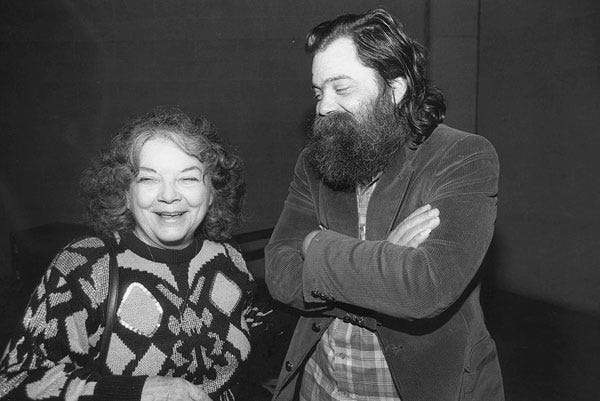

“His musicianship, his voice is 100% back,” said Clementine Hall, the queen of the acid ball when the Elevators were the house band. “But I don’t know if he has the same wit and intellect. He didn’t say a thing at dinner.” Her and ex-husband Tommy Hall, the Elevators’ jug player and LSD guru, met with Roky after his San Francisco return in March 2007. The Roky she met in 1965, when Tommy poached the hellfire singer from his high school band, the Spades, and put him in front of an adventurous combo from Kerrville called the Lingsmen, was funny, unpredictable, full of offbeat energy.

Although it’s assumed, because it’s such a garage rock classic, that “You’re Gonna Miss Me” was a hit in the summer of ’66, the record peaked at #55 on the Billboard singles chart. It’s noted more for what it inspired, plus the way it’s turned into a Texas “last call” rock anthem. The debut LP The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators (International Artists), which includes that first single, plus “Roller Coaster,” “Reverberation” and three songs from Powell St. John, was the first time “psychedelic” had been used to sell music. But this was no mere marketing ploy. This was a band that backed that far-out lifestyle all the way, with a “play the acid” mantra. They were right in time with Haight-Asbury, though 2,000 miles away.

“Tommy just wanted to get everybody high” Evelyn Erickson told me in 2007. “Well, Roky was already high. That’s where the trouble started.” Roky was the oldest of five boys, but always doted on like he was the youngest. Evelyn was a former opera singer turned religious, who liked to dress up and wrote poetry. Roky’s father Roger, an architect, was a workaholic and alcoholic, often away on business, so the first born became Evelyn’s neurotic obsession.

The band’s habit of ingesting LSD before every performance (except drummer John Ike Walton, who swore off after a bad trip) was not conducive to a long run. Who was thinking about the future during the time of assassinations and Vietnam? The band, featuring Stacy Sutherland’s proto-psych guitar, peaked with second LP Easter Everywhere, released 11 months after the debut. Third and final studio album Bull of the Woods, which finds Sutherland stepping up front for a barely-there Roky, was a frazzled LP that had its moments. But mind expansion had turned into musical excess. Without Roky’s voice, the Elevators were too much like everybody else.

And that was it for the beloved cult band, which experienced a flashback of kudos after the inclusion of “You’re Gonna Miss Me” (which Roky wrote as the 15-year-old) on the landmark 1972 Nuggets compilation.

The band became moot when Roky pleaded insanity to avoid the penitentiary after a marijuana bust on Mount Bonnell in Feb. 1969. But after repeated escapes from the Austin State Hospital to see his girlfriend Dana, Erickson was shipped off to the maximum security Rusk State Hospital for the criminally insane, where he spent two nightmarish years.

“The patient, a 21-year-old male, was incoherent when arrested for marijuana on Feb. 28, 1969. He has had private psychiatric care at Hedgecroft Hospital in Houston and has had electro shock treatments.” - from Roky’s medical report, 3/19/69, Austin State Hospital

Clementine Hall said Roky was damaged from the EST, performed without consent. "Roky escaped from Hedgecroft, and Tommy brought him to stay with me in San Francisco," she said of the summer of ‘68. "He was different. He said the Russians were talking to him through his teeth and that they wanted him to do bad things." Clementine took him to the beach where he let the waves crash into his body, the only thing that calmed him.

After Rusk, Erickson's once-trippy music took on horror movie themes, such as “Creature With the Atom Brain” and “I Think of Demons.” He called himself the Evil One, his band the Aliens and made some pretty good records on his good days. His 1976 single “Red Temple Prayer (Two-Headed Dog)” shared Rolling Stone’s top single of the year with “God Save the Queen” by the Sex Pistols. “Don’t Slander Me”/”Starry Eyes” was another triumph in 1984. On the eve of that single’s release, Roky told Third Coast magazine, “When I write a song I like to do it for an audience, but a lot of times my music scares them because they don’t understand what I’m trying to say.”

When he played the Ritz Theater in Austin in 1987, backed by Will Sexton, Speedy Sparks and other longtime supporters, it felt like the final Roky Erickson concert. He struggled and seemed lost. The magic was gone.

Roky didn’t play a show for 18 years. The resurrection started in March 2005 when Keven McAlester’s engrossing documentary You’re Gonna Miss Me premiered at SXSW. Days later, a clean-shaven and cordial Erickson played three songs at Threadgill’s to great acclaim. “It was advertised that Roky would do only one song, ‘Starry Eyes,’” said Peyton Wimmer, a longtime mental health counselor and family friend. “So, when he played a second and a third song, we were pretty shocked.” Four years of anti-schizophrenic medication and a new set of teeth, paid for by Henry Rollins, had given Roky the confidence to get back up in front of people. Six months later, he played to a crowd of well over 10,000 at the Austin City Limits Music Festival, tears of joy and disbelief streaming down the faces of fans. The next year, Erickson and his band, featuring former Explosives Cam King on guitar and Freddie Krc on drums, played Coachella and first-ever appearances in New York, Chicago and London.

“Guys like Roky make music that’s an amazing place to go,” Rollins told the Austin American Statesman as the comeback roared. “Coltrane and Miles and Hendrix were able to do this. It becomes more than the music and more than the lyrics- a total environment.”

On Christmas Day 2006, Erickson weaned himself off Zyprexa, his final medication. “I’ve seen some pretty remarkable recoveries,” said Wimmer, “but none as dramatic as Roky’s. It’s very rare for someone to come completely off meds and do so well.”

Sumner Erickson has to laugh. “It turns out Mom was right about Roky not needing medication.” The family reconciled after the screening of You’re Gonna Miss Me, with Evelyn telling her sons that she had no idea how much stress she’d been under.

Roky Erickson is the way he is because of the weird and lovely Evelyn, who could’ve been played by Ruth Gordon the day I met her. I think she was about 80, but you could see in her the 24-year-old. She was the kind of woman that might get up and dance to the jukebox at a bar. At 80. “He was babied and babied and babied by his mother into total helplessness,” Clementine Hall told writer Paul Drummond in the exhaustive bio Eye Mind: The Saga of Roky Erickson and the 13th Floor Elevators. “But I’ll say for her that she also made him an extremely loving and generous person.”

In 2010, Erickson made his first album in a decade and a half, backed by Austin indie-rock darlings Okkervil River. It seemed an odd musical coupling at first- Austin's mystical madman and its articulate Pitchfork band. Erickson’s triumphant return to performing was based on his ability to rock hard on such setlist exclamations as "Don’t Slander Me," "Two-Headed Dog" and "Slip Inside This House," so it was assumed that his comeback album would be one of screeching vocals and big sonic strokes.

But producer Will Sheff, the Okkervil River guide, had a different idea. True Love Cast Out All Evil (Anti Records) was a record of tattered little songs that had practically been abandoned, brought back in a spiritual whirl of dust and hope.

"I obsessively listened to about 60 songs that Roky had written, that were either never recorded or minimally released," Sheff said. Although he's a fan of Erickson's "horror rock" material, Sheff found himself drawn more to the songs of simple grace. "Roky was in a prison for two years and he had to come to terms with the thought that his musical career could be over," said Sheff. Such freshly recorded songs as the title track, the delicately moving "Forever," the haunting "Goodbye Sweet Dreams" and the album's hinge "Please Judge" were the soundtrack to the years when he went from Austin's golden child to its most notorious recluse. “These songs were written to serve the immediate purpose of keeping him sane,” said Sheff. “They're so powerful."

"Roky's one of the greatest rock 'n' roll singers of all time and a completely unique guitar player,” said Sheff, who earned a Grammy nomination for his liner notes. “But I think the way I've most been influenced by working with him is in his lyrics, the way he puts words together in a totally jarring way. He's created his own private vocabulary.”

If not the greatest musician Austin has produced, Roky Erickson is certainly the most influential. In March 1966, Janis Joplin and the 13th Floor Elevators shared a stage in Austin for the first and only time. It was a benefit for ailing fiddler Teodar Jackson at the Methodist Student Center on the Drag. Janis belted out blues songs accompanying herself on an acoustic guitar early in the show and stood at the side of the stage when Roky and the Elevators practically levitated the crowd with their intense mind and soul control. “Janis took a long, hard look at Roky and his energy,” recalled St. John, who was also on the bill. “She was riveted.” Three months later, Joplin was a screeching rocker herself, fronting Big Brother and the Holding Company.

The year Joplin died of a heroin overdose, 1970, Erickson was locked up in a hospital with murderers and rapists. His mind was going, going, going…

But coming on 50 years later, Roky toured the world in the palm of worship until he passed away on May 31, 2019 at age 71. He was not only a garage rock legend, but lived the lesson ‘60s psychedelia ignored. Time, it turns out, has the answer.

This is a chapter from “Ghost Notes: Pioneering Spirits of Texas Music” by Michael Corcoran (TCU Press 2020).

Beautifully done.

You always come up with great, behind the scene stories. Usually when I talked to Roky, he would answer very simply, like "yes" or "no", unless I asked him about his music. Once I asked him if Two-headed Dog had something to do with Cerebrus and he told me that some people thought that, but others related it to Pavlov's experiments. I told him another song sounded kind of like a Buddy Holly song and he said that he wrote it as a tribute to Buddy. Because his answers were usually so short, I asked him if he'd ever met Brian Wilson, since in recent interviews, he seemed to produce similar answers, so I thought maybe they had the same type of thought patterns. He said no, but he'd like to.