Ryan Bingham: Destiny's Cowhand

"Yellowstone"'s ringer coming to Whitewater Amphitheater Sept. 3 and 4

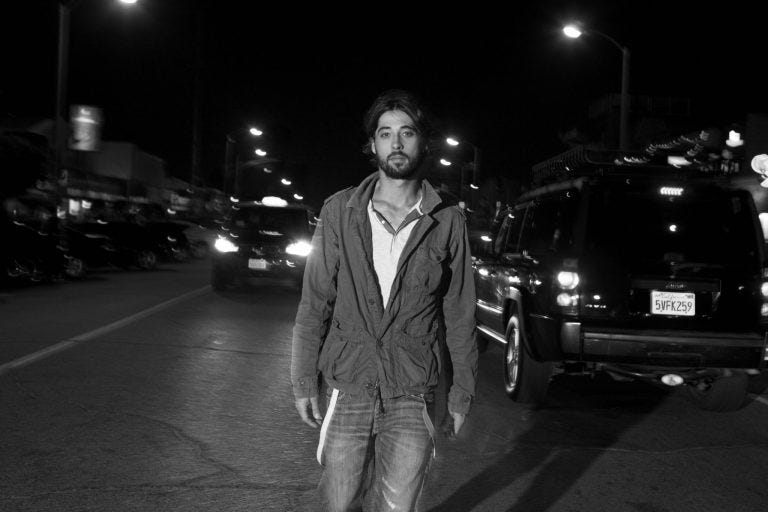

The last show I saw before the Pandemic was one of the five best I’ve ever seen in a club. I followed Ryan Bingham like a groupie from San Antonio to Alpine- a five-hour drive- because the former Austin couch-surfer was making a rare detour off his route of 2,000-capacity theaters to play Railroad Blues, which is not quite the size of the Continental Club.

A theme of several of Bingham’s songs is that you can’t truly escape your past. “How many times can I forgive you?/ If you are always on my mind/ I've tried so hard to outrun you/ but you are never far behind,” he sings of his turbulent upbringing by alcoholic parents always on the verge of eviction.

But in the case of Railroad Blues, his memories are a positive anchor for a career that’s spanned six acclaimed albums and finds him starring in the hit TV series Yellowstone.

It’s been a long time since Bingham wondered if what he had was any good. But he hasn’t forgotten that guy.

“When our band was starting out in Austin, we were always broke, and times were tough,” Bingham told the “Ry-hards” in Alpine. “But Railroad Blues was a special place to play.” That 2005 crowd got the gravel-voiced Bingham like no one else before, and the jubilant drive back to Austin felt like 45 minutes. Introducing “Big Country Sky,” Bingham said, “most folks think I wrote it about Montana, but I wrote it about right here.”

It’s a song he rarely, if ever, plays live, but when Bingham stumbled over a lyric, the crowd took over: “It’s just another sacred sky/ Make you wanna grow wings and fly/ Then never touch down/ Be a certified member of the lost and never found.”

Bingham won an Academy Award (best song for “The Weary Kind”), a Grammy and an Americana Artist of the Year award before he turned 30 in 2011. But he also lost both parents, whose substance abuse he addressed in the starkly autobiographical “Nobody Knows My Trouble,” from 2015’s Fear and Saturday Night.

“I have a sister who’s two years older and the day she turned 18 she said, ‘I’m outta here,’ ” he recalled. “I couldn’t wait to get out myself.” Bingham’s mother drank herself to death in 2008 and his estranged father, going through a divorce, shot himself in the head a few years later.

It was a sad ending for two of the chosen ones at Hobbs High in New Mexico, where mother Cindy Morris was the Class of ’73 homecoming queen and father George Bingham was the star quarterback. When Ryan was five, his grandfather sold the family farm, so his father chased oil field jobs from Bakersfield, CA to Midland-Odessa to Houston, dragging his family along. Ryan attended five high schools in Texas, graduating from Stephenville High, where he started bullriding.

“When I hit the trail with the rodeo it was like joining a gang,” Bingham said. “Everybody looked out for each other.” After Bingham’s front teeth got knocked out by one buck he started really practicing guitar.

I met with the laidback Bingham in late ‘19 for a Texas Highways story. “Moving around so much as a kid, I didn’t know who I was or where I was from,” he said from his tour bus outside the Aztec Theater in San Antonio. “The rodeo became my family. But then I discovered the guitar and found my new sense of identity.” His mother gave him his first guitar when he was 16 and moving from Houston to Laredo to live with his father. “I didn’t ask for it. I guess she just felt that I needed it, but I didn’t have any ambition to learn how to play. I didn’t think I had any ability. Then a fella who hung out with my dad played (mariachi standard) ‘La Malaguena’ on it and he showed me how to do it, a little bit at a time.

But I found me a guitar/ One lonely night in a border town/My pain, I started to write it down/ But it wouldn't stay away from me - “Nobody Knows My Trouble”

Bingham had his first breakthrough as a writer at age 20 when he was trying to learn how to play the harmonica on a neck rack a la Bob Dylan and Neil Young. “I kept going from the G chord to the C chord on the guitar and I found a melody on the harmonica,” Bingham said. He wrote his signature tune “Southside of Heaven” that day. “It’s still the one song I have to play every show.”

The rodeo afterparty was always at the tailgate of Bingham’s pickup, where he’d sing some Dylan, Prine and Billy Joe Shaver and every once in a while someone would ask “Who did that song?” and it was one of his.

Bingham was influenced by other Texas songwriters, especially Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt, but when he started playing his own music, it sounded more like what he heard on the West Texas rodeo circuit, where Merle Haggard and Creedence Clearwater Revival coexisted on every soundman’s mixtape.

A cassette with Bingham’s name scrawled on it made it into Lubbock songwriting mentor Terry Allen’s tape deck, and at the 2006 wedding anniversary party of Terry and Jo Harvey Allen, Bingham held his own in a guitar pull that included Joe Ely, Guy Clark, David Byrne and Butch Hancock. As Ely’s opening act at the Cactus Cafe later that year, a 25-year-old Bingham attracted the attention of A&R exec Kim Buie, who signed him to Nashville’s Lost Highway label. The stunning debut Mescalito shot out of the chute the next year like Bodacious, with critics championing a modern dust bowl troubadour and busting out the Thesaurus for new ways to describe his raw, husky voice.

What did it for me was a powerful performance at ACL Fest in 2008, on the tiny BMI stage. Bingham and his Dead Horses were on fire that evening, with drummer Matt Smith and bassist Elijah Ford engaged like padlocked testicles, while Corby Shaub’s slide and mandolin were free to roam the delirious fields. My knees almost gave out on the set-closing “Bread and Water,” when Ryan and the Horses were Tom Waits backed by Social Distortion. I remember my review because it was only one word: WHEW!

The German filmmaker Anna Axster, who directed the videos for “Southside of Heaven” and “Bread and Water,” would become Bingham’s wife and business partner in 2009. She ran their Axster Bingham company while having three kids, but the marriage didn’t survive the Pandemic. Bingham filed for divorce in June 2021.

In conjunction with Live Nation, the Binghams put on a festival at Luckenbach in April 2019 called The Western Fest. A blue norther made for a June followup in 2020, but it was canceled, along with every other musical event after March 2020. Here’s a bit of an interview I did to advance the never-held second Western Fest.

Did you play in Luckenbach when you were starting out?

Yes, sir. It was one of the first places I played after moving to Austin (circa 2004). Loved the people, the songwriters, the characters. Some nights in the winter there would be only 10 people, so we’d sit by the fire-burning stove and pass the guitar around. That’s where I really learned to write songs.

Had you been a big music fan growing up?

Oh, yeah! My family owned a joint called the Halfway Bar because it was halfway between Hobbs, New Mexico and Carlsbad. My Uncle Clay ended up with all the records (after the Halfway closed in the early ‘90s and Bingham moved back to Hobbs at age 13 to live with relatives), and he played me everything from Merle Haggard and Bob Wills to Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones.

My uncle also had a bunch of Dylan stuff and “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall” was a turning point for me. I really grew up listening to those records, sitting around with him. One of our favorite records was Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen live at the Armadillo World Headquarters, with Bill Kirchen on guitar. One time my uncle came to visit me in Austin and we went into this little bar on South Congress (Ego’s) to get a beer and there was Bill Kirchen onstage. That blew us away!

How did the collaboration with Charlie Sexton on the latest album American Love Song come about?

A few years back I had the opportunity to go on tour with Bob Dylan, with Wilco and My Morning Jacket also on the bill. Charlie was playing guitar with Bob, so I got to really know him on the road. I’ve always enjoyed being around Charlie and I noticed how well he treats other musicians. I wanted to go back to my roots and musical influences, from the blues and Texas swing and Cajun and zydeco and border music. And Bob Dylan, of course. Charlie knows that stuff inside and out. I knew I wouldn’t have to tell him about Lightnin’ Hopkins or Guy Clark or the Texas Tornados.

Did you meet Bob? He’s a pretty private guy.

Oh, yeah. Dylan would call us up- me and Jeff Tweedy from Wilco and Jim James from My Morning Jacket- to sing “The Weight” with him. I can’t tell you how much of a thrill that was. We did it, like five shows in a row and afterwards Bob would shake my hand and say ‘Thanks, Ryan.’

You’ve performed “Wolves” as your character Walker on Yellowstone. Did you write it for the TV show?

No, it was inspired by the epidemic of gun violence in this country and the kids from Parkland High who organized the March For Our Lives. The way I saw grown men and women respond to these kids with hateful rhetoric had me thinking about the bullies I had growing up, me always being the new kid in town. And I was thinking of the folks who face discrimination on a daily basis, like my black friends from Houston. They were bullriders, too, and when we’d travel together to rodeos, we’d experience racism because I was white and they were black and some folks didn’t think we should roll together.

I’ve seen you playing solo acoustic in listening rooms and raging with a full band at amphitheaters, like Whitewater, but you’re playing a lot of theaters on this tour.

We’re really digging some of those great old Texas theaters. I like when everyone has a seat and they’re really listening. The night after we did the Paramount in Austin, one of my favorite places I’ve ever played, we went up to Dallas and played a big square room with about 4,000 people jammed in like a tuna can. A lot of them were drunk and rowdy and made it hard for the folks who came to listen to the music. It was a real shit show. You want it to be an enjoyable experience for everyone, especially the people who tell you how this song or this record got them through some tough times. That’s what you make music for, to get you through some tough times, and to help some other kids that are going through what you went through.

A Ryan Bingham Playlist

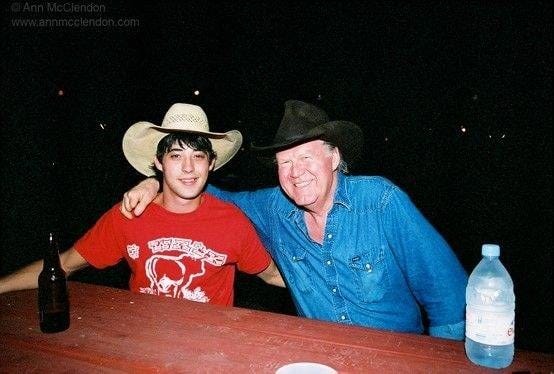

I grew up with Ryan’s parents. His dad George lived with me during the week, we both played football, and went home to the family ranch on the weekends. His folks had the world at their feet, and I will never understand how it came off the rails. Really proud of Ryan to have overcome a lot in his youth.

Found this while Googling Ryan Bingham in my hotel room in Hobbs, New Mexico, where I am visiting for work. Great read. Can't wait for your book.