With Kathryn Ferguson’s Sinead O’Connor doc Nothing Compares now streaming on Showtime, I yanked this 28-year-old review out of the archives. Originally ran in the Dallas Morning News.

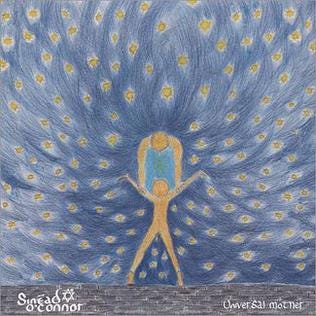

"All babies are born out of great pain," Sinead O'Connor sings on her new LP, Universal Mother. "All babies are born into great pain."

O'Connor doesn't always say what she's trying to say, but there's no doubt about the theme of Universal Mother, the singer's first album of original songs since 1990's I Do Not Want What I Haven't Got. A recurring subject is child abuse and its lingering effects in adulthood. It's also about damage control, trying to break the chain of violation. Mothers have the power and the responsibility to make the world a better place, Universal tells us. Abuse and neglect only lead to danger and depression.

After four tumultuous years in the wincing public eye as Sinead O’Contraire, the outspoken 27-year-old Irish singer, who has chronicled in interviews a childhood of beatings, doesn't want to be kicked around anymore. "My body's not a football for you," she sings on “Red Football,” and you're not sure if she means her parents or the media. On the LP's final cut, she turns defiance into graciousness. "Thank you for not hurting me," she sings, as if there really is hope after all the remembering, grieving and forgiving she calls for on this release.

Often dreary and melodramatic, Universal Mother is an ultimately stunning work because it doesn't flinch in the face of its shortcomings. Catharsis can be insincere and manipulative, but a voice as ravishing as O'Connor's gets away with it because it could only come from deep inside. If any singer has needed to heal herself with her songs, it's she who has balanced exquisite music with an often erratic personal life.

In his self-portrait Harp, author John Gregory Dunn relates that the first unwritten rule of Irish social survival is the injunction, "Don't make waves."

"Don't make waves meant know your place, don't stand out so the Yanks could see you, don't let your pretensions become a focus of Yank merriment and mockery," Mr. Dunne wrote. It's advice that Sinead could've ridden to the top of the modern pop world.

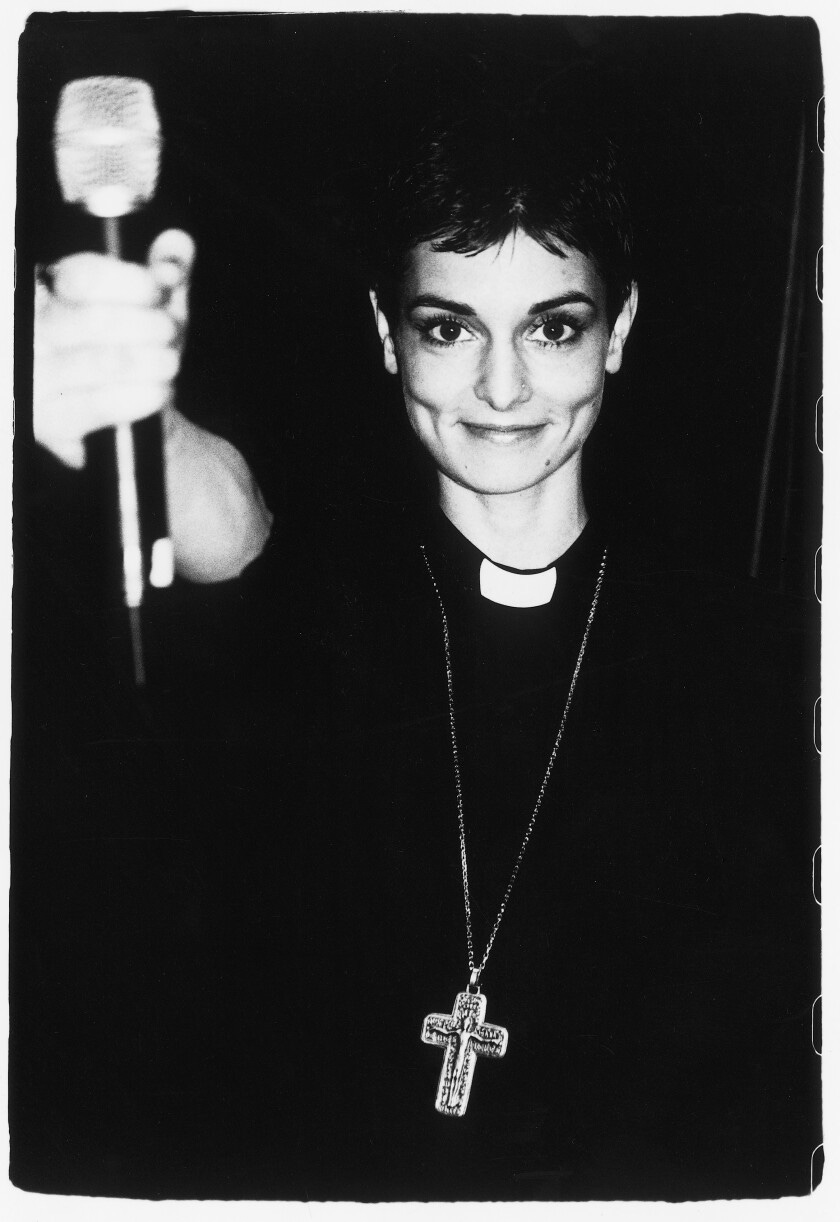

She was a singular new talent - a shaved-headed Streisand in combat boots. But after a few of her headline-grabbing outbursts, the public started assuming an attitude of "Shut up and sing, cue-ball head." After a highly publicized attack on the pope, the exhortation was simply, "Shut up!"

Ms. O'Connor became monologue fodder for Jay Leno, and Frank Sinatra ripped her in a letter that ran in the Los Angeles Times. Even worse, she was booed by the crowd at the '92 Bob Dylan tribute concert in Madison Square Garden.

Her detractors, who seem as numerous as Rush Limbaugh fans, will claim that Ms. O'Connor brought most of her woes upon herself. Soon after blasting onto the scene with her 1987 LP The Lion and the Cobra, Ms. O'Connor became one of those reluctant voices of her generation. She seemed to think that "avatar" meant "publicist's nightmare," however, as her "reluctant" voice nearly went hoarse from giving her opinions.

The outrageous pixie tested the waters of contention by canceling an appearance on Saturday Night Live in 1990 because it was hosted by misogynous chowderhead Andrew Dice Clay. Later that year she refused to perform at a New Jersey venue where the national anthem was played before concerts. Her causes started to become silly when she boycotted the Grammy Awards as too commercial, and folks wondered how long before they'd see Ms. O'Connor protest pro wrestling matches as fixed.

Ms. O'Connor plunged headfirst into the icy pools of controversy on Oct. 3, 1992, when she tore a photo of the pope and said, "Fight the real enemy," during a performance on Saturday Night Live. Suddenly, she had a few hundred million Catholics ticked off, and her career took a dive.

After her underrated 1992 LP of standards, Am I Not Your Girl?, stiffed, and her family disowned her when she went public with detailed allegations of her abuse at the hands of her now-deceased mother, Ms. O'Connor hit rock bottom. In the depths of despondency, she says, she tried to commit suicide on Sept. 7, 1993, by washing down a handful of downers with a bottle of vodka. She then went into a substance abuse program.

With her thoughts now insulated by an inch and a half of hair, Ms. O'Connor chips away at the public's negative perception of her on Universal Mother. A musical therapy session that puts the shrink in shrink-wrap, it's a certifiable bringdown with a bar code. But Ms. O'Connor is one of the few singers who could breathe relevance into the empty-headed lullabies and ethereal smoothies that pop up throughout some of the album.

One of the problems with O'Connor is that she became famous at age 20, before she really knew much about life: Her ideas were vaulted into the limelight simply because she had a nice singing voice.

In a letter to a journalist that was published in the September '94 issue of Britain's Q magazine, she owned up to some of her transgressions. "I never want to go through what I have gone through in the last four years ever again," she wrote. "And I accept my own responsibility in all of it. I am very sorry for all the hurt that I have ever caused to anyone while on this journey. Of growing up."

It's entirely fitting that Universal Mother is being released on Thursday, instead of the record industry's customary Tuesday, to coincide with Yom Kippur. No, Ms. O'Connor hasn't pulled a Sammy Davis Jr. and embraced the Torah, though she does sample Fiddler On the Roof on “Famine.”

Ms. O'Connor keyed Sept. 15 for the release date because it's the Jewish Day of Atonement and she's intent on making amends. On a track sure to be the album's most-discussed, she gives Kurt Cobain's “All Apologies” a haunting reading that virtually changes the meaning of Nirvana's version. Where Mr. Cobain scowled a tinge of sarcasm into his apologies, Ms. O'Connor delivers hers with remorse. It's a fitting dirge to the tragedy of Mr. Cobain's suicide in April.

Despite its generally soothing sound, Universal Mother is not without its anger. It opens like a rap album, sampling a militant speech by feminist Germaine Greer, before kicking into “Fire On Babylon,” a beat-driven tune about being beaten down. Twelve cuts later, on “Famine,” Ms. O'Connor raps about the systematic extermination of the Irish culture. The Fiddler snippets are there to show that the oppressed can rebound as long as they hold onto their collective identity. "They gave us money not to teach our children Irish and so we lost our history/And this is what I think is still hurting us," she says, before breaking into the "All the lonely people" refrain from The Beatles' Eleanor Rigby.

Though this all sounds like an Eire version of the Afrocentric ire of recent rap records, this LP is not ready to be subtitled Womb! There It Is. On this one, the street ends where the streams of self-exploration begin.

Thank you for this. O’Connor has long been one of my favorite singers. I have read other less empathetic reviews; yours was a nice change of pace. I hope she has found some peace now.

I don't know this record but your review itself has aged very well. I bet she'd like it too... Bravo!