SRV: The Fan Who Would Be King

"I wanted to be so much like Jimi, I almost died like him"

Every era has had its guitar heroes. The '50s had Chuck Berry, Link Wray, James Burton, and Duane Eddy; in the '60s, Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton were called "god"; the '70s, a decade of virtuosity, found Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, Carlos Santana, and John McLaughlin joining the temple of guitar greats. And we can’t forget the great Johnny Winter of Beaumont, whose blues guitar was both authentic and psychedelic, and Eddie Van Halen, who did things with the strings nobody’d ever done before- or since.

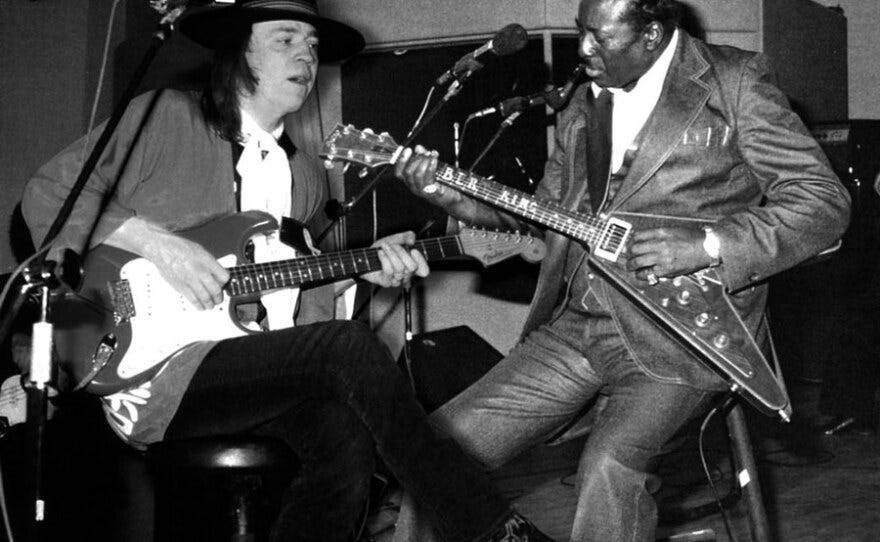

The '80s belonged to Stevie Ray Vaughan, who began the decade playing to 50 people a night at such Austin clubs as the Continental, Rome Inn and Steamboat, but ended it atop every Guitar Player poll in the blues category. All his albums, beginning with 1983’s Texas Flood, went gold or platinum, and his concerts almost always sold out. But even more significantly to the reverent Stevie Vaughan, he became his idol Albert King’s favorite young guitarist.

And though he died eight months into 1990, SRV pretty much owned that decade, too. Released a month after his death, Family Style, the duet LP with his brother Jimmie Vaughan, went platinum and received a Grammy. The next year came The Sky Is Crying and then, in late ’92, Epic released In the Beginning, a 1980 concert recording from Steamboat, broadcast live over KLBJ-FM, that shows Stevie before producers took the fuzz off his dice. Those albums are better than “posthumous” usually has to be.

The Vaughan family put the clamps on further releases that may water down the legacy, and said no in 2002 to promoters who wanted to call their annual Zilker Park event The Stevie Ray Vaughan Music Festival. Both sides dodged a mortar with C3 doing fine with ACL Fest and the Vaughan name not having to be connected to the likes of Iggy Azalea and laptop “musicians.”

The Sky Is Crying, previously unreleased studio tracks from 1984-1989, is a relaxed tribute not just to Vaughan, but the guitarists who influenced him. Stevie Ray was, first and foremost, a fan; all great young blues guitarists are. You can't help hearing the ecstacy in his fingers and his voice as he covers songs made famous by Albert King, Lonnie Mack, Jimi Hendrix, Kenny Burrell, Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf.

A few months before Vaughan's death in a helicopter crash, I was asked to ghost-write a magazine story titled "My Guitar Heroes by Stevie Ray Vaughan." The idea was for Stevie to give a monologue about his idols, with occasional prodding by me, then I would translate his thoughts to article form. Having interviewed Vaughan four years earlier, during his days of drug and alcohol abuse, I knew how withdrawn he could be. His rehabilitation had been well-publicized; still I had trouble picturing Vaughan as any thing but the painfully shy person whose whole life was the shapely peninsula of wood and wires he held in his hand.

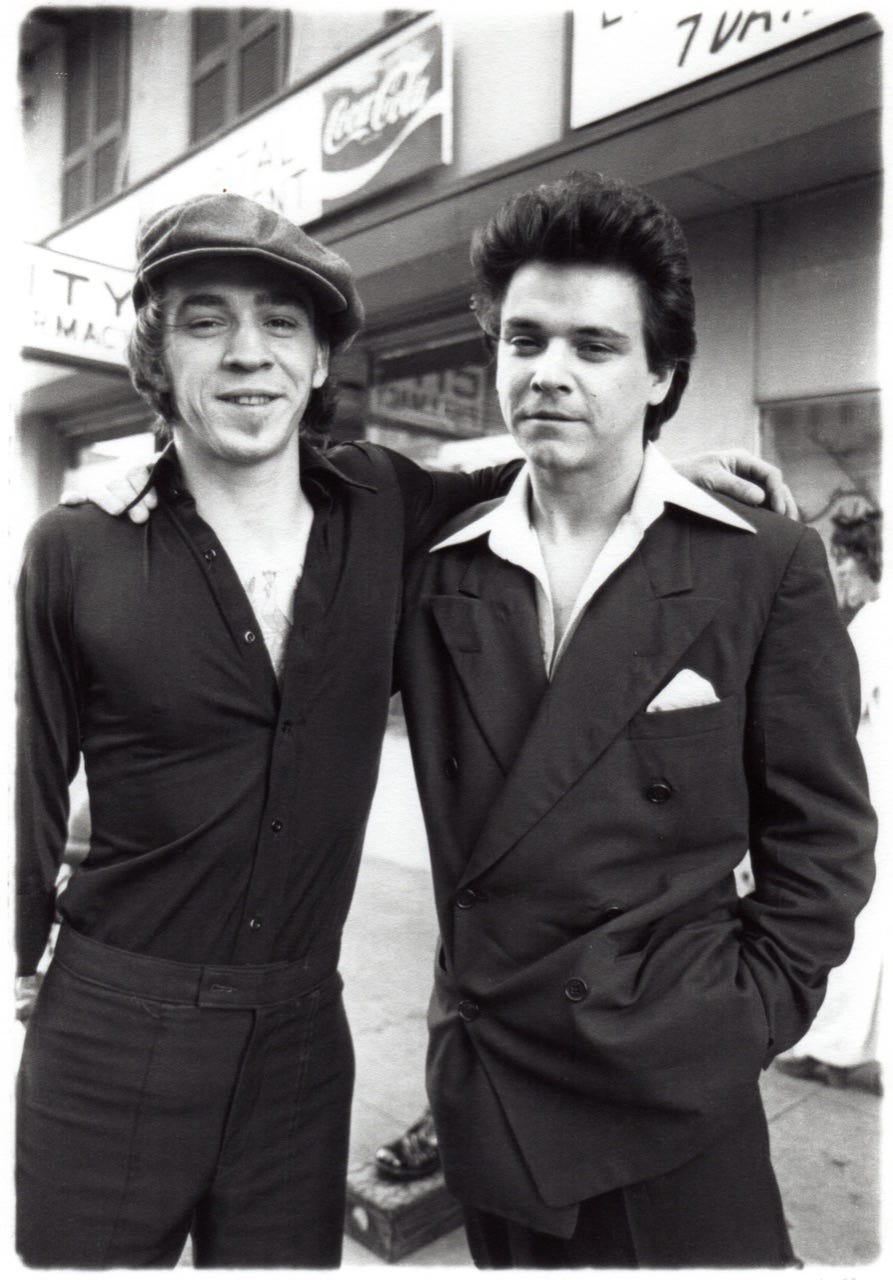

When Vaughan started talking about his heroes, however, his speech was articulate and full of zest. Intervention on my part was almost completely unnecessary as he recounted important guitar players in his life. His first major influence was brother Jimmie, three and a half years older, who introduced Stevie to the music of T-Bone Walker, Lightnin' Hopkins and John Lee Hooker among others. Stevie was 9 years old at the time.

“When we were first startin’ off we had some friends of the family show us stuff, like one guy played with Ray Sharpe and the Razor Blades, so right off the bat we were playin’ “Linda Lu,” Jimmy Reed — really hip stuff for little kids,” said Stevie. “Jimmie came right out of the chute, bringing home records by everyone from Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, B.B. King and Buddy Guy to the Beatles and Hendrix to Wes Montgomery and Miles Davis — all this stuff at the same time. I don’t know how he got the idea to be so hip so quick.”

The first record Stevie bought was “Wham!” by Lonnie Mack. "I went into a record store and asked the guy at the counter to recommend a single with great guitar playing, and he played `Wham' for me,” recalled Stevie. “It was just the wildest thing I’d ever heard. I listened to it over and over again for a week. Then when I got more of his stuff, I loved the way his slow tunes sounded like gospel and the blues at the same time. After Lonnie Mack, I remember Buddy Guy and Muddy — that was pretty heavy stuff for me. And then it wasn’t too long until I ran into Albert King. The album was King of the Blues Guitar.”

Blues was always Vaughan's forte and, with vivid clarity, he remembered the day that he decided to become a musician. Stevie was about 12 and working as a dishwasher in Oak Cliff. “I was cleaning out the trash bin and I slipped and fell into a big barrel where they poured the hot grease. Luckily it was empty at the time, but if I had fell 30 minutes later I would’ve been fried. Well, anyway, the woman who owned the place came out yelling at me because I had broke the lid to the grease barrel. She didn’t even ask if I was all right. Well, I got so mad that I quit that day and told myself that I was going to be a guitar player like Albert King. I knew that’s what I wanted to do — no ifs, ands or buts. And I haven’t had another job since.”

Jimmie was good on the guitar as soon as he picked it up, while the younger brother had to really work at it. Mainly that was because Stevie’s first guitar was a piece of shit. “It was a Masonite version of a Roy Rogers guitar — a copy of a copy — and it didn’t work. The only way you could tune it was to take three strings off and tune it like a bass. When Jimmie got his first electric guitar, I got his acoustic.”

The brothers jammed together for hours every day, just calling out songs. “I remember the first time Jimmie and I played a talent show and we realized in the middle of a song we’d played dozens of times that we’d never ended it before. We knew we had a ways to go.”

There was no way a kid with an electric guitar in the ‘60s was not going to be blown away by Jimi Hendrix. "When I was a teenager, Jimi was what did it for me," Vaughan said. "He taught me how to play with emotion, how to find that one right note, the one that goes right to your knees."

As a young adult, Vaughan dressed as Hendrix on Halloween and also adopted other elements of Jimi's persona during the other 364 days of the year. Like the "Fistful of Dollars" hat. The scarves and kimono shirts. Like LSD, speed, heroin, cocaine and alcohol. "I wanted to be so much like Jimi that I almost died like him," Vaughan said.

But he didn't die like Jimi. He died like Buddy, Otis, Patsy, Duane, and Eddie: too young, and through no fault of his own.

After his brother passed away on Aug. 27, 1990, Jimmie Vaughan, who left the Fabulous Thunderbirds in ‘89, stayed away from the creative end of the music business for almost three years. He spent his days working on his cars, listening to the doo-wop rock 'n' roll of the 5 Royales or strumming an acoustic guitar in his back yard, under a pecan tree. He lost his love of the stage.

But a 1993 offer from Eric Clapton, who headlined Stevie Ray's last show, gave Jimmie the incentive to "get off my butt and put a band together," he said. Soon after returning from opening six Clapton shows at London’s Royal Albert Hall, Vaughan started assembling the material for his first solo album Strange Pleasure, which, like Family Style, was produced by Nile Rodgers. One of the new tunes was "Six Strings Down," a tribute to Stevie Ray sent to Jimmie by Cyril and Art Neville.

"That song just sat there for months," Vaughan said. "The first part goes `Alpine Valley, in the middle of the night/ Six strings down on a heaven-bound flight,' and I had to turn it off. I just couldn't listen to it. I didn't want to be reminded."

Over time, he realized what the song needed, and wrote a chorus saluting other deceased blues greats, like Albert King, Lightnin' Hopkins, Albert Collins and T-Bone Walker. "Stevie would've liked that," Jimmie said. He was no longer bound to earth, but up in the Fender Stratosphere with his fathers and brothers of the blues.

MORE SRV. The chapter from All Over the Map: True Heroes of Texas Music

Lead photo of Stevie Ray Vaughan by Daniel J. Schaefer.

his speech was articulate and full of zest. I believe it. Listen to Van Morrison talk about Leadbelly. And you're like, "Wait... is this Van talking?"

On Sunday, March 26th I reserved the Lightnin' Hopkins suite at the Heights [concert] Theater in Houston for the new documentary "Jimmie and Stevie Ray Vaughan: Brothers in Blues", hosted by director Kirby Warnock [ex- Buddy Magazine]. My group of eight included long-time musicians [one -- also owner of a studio -- began in the 1950s]; a manager of a live-music hall; and a well-known, former Houston DJ [in the Texas Radio HOF]. ALL of us were blown away by this film! In fact, the entire audience gave Kirby and his project a standing ovation. Find a way to see it ... SOON!