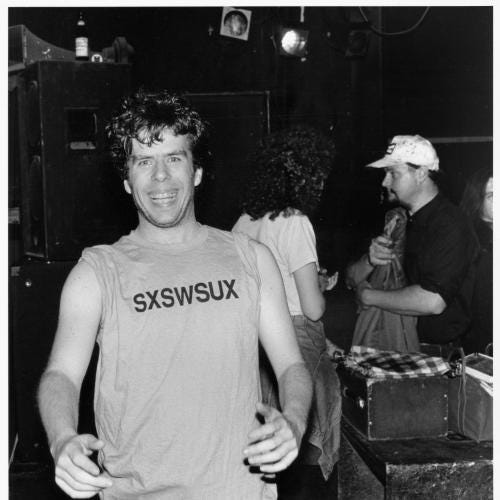

SXSW in the early '90's: "They really like us!"

The party of the year was wild, no thanks to the fire marshal

I never worked for SXSW, but I helped out in the beginning, recruiting industry folks for panels in exchange for a free room at the host hotel. Mid-March Austin, in the early ‘90s, that was better than a bungalow at the Chateau Marmont.

It was usually a suite, but the bigger side was the green room for panelists to talk a bit before they went on. Since my room had the bathroom, I had to be outta there by 10 a.m. each day. I have to admit that some days I’d stay in bed until noon and never even noticed the morning whizzers.

Some nights a kindly SXSW volunteer would bring a band with no place to stay and let them crash in the green room. One time it was Souled American, an Illinois band who were mortified to have a wired, drunken suitemate who wouldn’t stop talking about Cheap Trick, the Cubs, and how you can’t get those poppy seed hot dog buns in Texas.

Sleep was for Sunday, when our annual Fat Wednesday-through-Saturday celebration was put to bed.

Being an Austinite when SXSW became wildly popular, but not yet out of control, was like having a hit for four days. Austin became “what’s hot.” We thought we had something special here, and music industry wholeheartedly confirmed that, even loving this town in ways we took for granted. Shiner Bock became Coors in the ‘70s- the exotic beer worth travel. Meanwhile, crappy clubs on Sixth Street were CBGBs for a night, and Tex-Mex replaced creole as the South’s haute cuisine. Then there was the perfect weather. The climate of Texas in March matches the Bahamas, but only we had the Spin party! Yee-haw! (Remember when “Yee-Haw!” was in the subject line of every email promoting a SXSW appearance?)

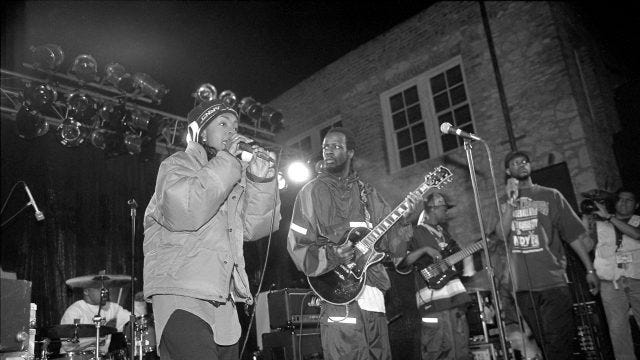

Austin knew how to party, the word got out, and from 1990 to 1999, the number of badgewearers quadrupled. The faces of newbies said, “there’s no place I’d rather be,” and all the bands played their asses off. They’d come from far away at great expense to play for the agents, managers, record companies, festival bookers and journalists who could take them to the next level. Fuck a hangover.

My best year in service to Southby was 1991, when I was primarily responsible for getting Rosanne Cash to keynote. I pitched the idea to her at the end of a fascinating interview in Nashville, and SX followed up. I also scored big points that year by getting Chris Morris of Billboard to come. Not only did he and Claudia Perry from the Houston Chronicle hilariously liven up the usually dead rock critic panel, but Chris put SXSW on Billboard’s radar. (Until Entertainment Weekly became a sponsor and Billboard editor Timothy White deemed SXSW no longer an industry event worth coverage.)

Covering SXSW hardcore from 1992, with the Dallas Morning News, to 2011, with the Statesman, was good for my finances and self-esteem, but what I wouldn’t have given to be free in Austin in March again! By the time I took early retirement at age 55, I was too old to party like it was 1991.

That was the year SXSW drinks to forget. It was the first time the music conference was held when UT students were in town, a week before Spring Break, and the frats and bowheads packed Sixth Street. The fire marshal overreacted to the crowds, so many a set was halted as load cards- which had been lowballed for favorable tax rates- were enforced regardless to how full the clubs actually were. Frustrated that no one would voluntarily leave El Carribe Mercado at the marshal’s insistence, the owner shot a pistol into the ceiling. Everybody was taking speed to work as hard and party as long as they could.

It was the birth of the entitled townie at SXSW. They thought their $39 wristband guaranteed admission to any show they wanted to attend, so there were near-riot situations at several venues, as the badge-wearers waltzed in. Maybe the worst was for Lucinda Williams at La Zona Rosa, when it was owned by Marcia Ball and husband Gordon Fowler. The boutique club was made even smaller by the mad counters in the red trucks, so maybe 100 were inside with about four times that many outside and furious.

I remember ‘91 as the year we followed Southern Culture on the Skids from their great show at the Ritz to a party at the Embassy Suites . I think it was in Mojo Nixon’s suite because there was Indian leg wrestling going on. Some guy showed up with a trash bag full of mushrooms, but it was late so I took mine to go.

The next morning a friend came up to me, and excitedly asked, “did you take those mushrooms?!” Not yet, I said. “Good! They’re poisonous!” he said. “My friend’s at the hospital right now getting his stomach pumped.” Oh, shit, I needed to alert some of the others! I remembered a guitar player called Roscoe reaching into that bag of fungus, so I got together a posse to find him. “Have you seen Roscoe?” We raced to Liberty Lunch, where he was onstage with Mojo, and playing brilliantly. Whew! After he came off stage, we warned him, “don’t take those mushrooms!” Roscoe had a big stoned smile. “I took ‘em a few hours ago, and they’re great!” But one guy had to go to the hospital, we said. “That guy’s a wimp.” I’ve had those panic attacks where you think something you ingested might kill you, but who goes to the hospital during SXSW?!

On the Sunday night of Southby ‘91, True Believers had an unannounced reunion at the Hole In the Wall. “We’re gonna lock the door at 2 a.m. and play all night,” Alejandro Escovedo announced about half an hour before last call. I popped in the “poison” mushrooms I’d been saving for Monday and dug in for a wild night and morning. But the band played only five or six songs. When did Alejandro become George Jones? Dammit, I was just starting to come on. Now, what was I supposed to do all night? And it was too late to get beer.

I was walking with Debbie Pastor in West Campus, looking for a party at around 3 a.m., when we happened upon flames in a familiar place. The fire trucks arrived just as we did, and Pastor had her miniature movie camera out. “This is the South by Southwest office,” I told the head fireman. “I work here.” The fire was started with a stack of Austin Chronicles at the door, and the damage wasn’t extensive inside- mostly smoke and water. “Why don’t you call your boss,” the fireman said, after they put out the mini-blaze, so I went inside and got Louis Black on the phone. He thought he was dreaming and went back to sleep. Then I called Roland Swenson, who arrived in a matter of minutes.

“Do you have any enemies?” the chief asked Roland. The day after SXSW ‘91? You could start with 400 angry Lucinda fans. Kinda fitting, though, that the year the fire department dampened the fun, they’d end up putting out a fire they probably helped cause.

I explored the back office where most the SXSW prep was done and found a trash can full of iced-down Miller Lite- the fest’s beer sponsor. And I sat there drinking one after the other while Deb asked me questions while filming. “Let’s make love on the burning embers,” I said at one point. To which Debbie, appropriately, laughed. Maybe a little too long.

Years later, in 2010, when Arts & Labor was making a documentary about SXSW that used Pastor’s footage, I was told that within the Chron/SXSW circle I’d been considered a suspect in starting the fire. “Oh, right, he just happened to be walking by at 3 a.m. on a Monday morning.” I know it looks bad, but although I’ve gone to great lengths for free beer, I draw the line at arson.

The transition year for SXSW, when it was no longer considered regional, but international, may have been 1994, also known as the year of the Man In Black. Besides a musical keynote, when he played solo acoustic numbers from his upcoming Rick Rubin-produced American Recordings, Johnny Cash did a set with his band at Emo’s that’s become legend. When Beck followed him, he opened with an apology.

I would like to think that Roseanne Cash convinced her father to do SXSW. But by 1994, everybody knew about the magic in Austin the third week of March. Paradise never could keep its mouth shut.

By the end of the decade, former buzz act Lucinda Williams was the keynote. And prestige artist Tom Waits came to play, basically for free, at the Paramount Theatre. Don’t automatically knock playing for exposure. That’s the rock SXSW was built on. And the beer hose that made it such fun. It was always an honor to be part of an audience that could make a difference in some band’s career. Or get fucked up, trying.

My SXSW history:

'87: wazzat? I went to a few shows, unaware that it was an actual festival/event

'88: no biggie - was out of town on a UT Biology dept. field trip

'89: my first knowing SXSW attendance - FANTASTIC experience - I could 'make my own bill' by hop, skip, and jumping from club to club. Invariably I ended up at Antone's before Clifford locks the door before last call and declares us 'guests at a private party..'

'90: SXSW gets too big for its britches - I could get into ANY club that I wanted if I showed early. But once I left, I couldn't get in ANYWHERE. One harried bar maid explained it thus - 'David- YOU are here every freakin' week. THESE shmoes are here THIS week, and we gotta keep 'em oiled n happy.' So after overanalyzing the schedule, I made the Continental Club my chateau de music for the weekend.

'91: didn't bother. Graduated UT, went off to grad school and life beyond.

Am I the only one who'd really like to see that film of Deb's? Mushrooms and beer!