"T for Threadgill," Father of the Austin Music Scene

Kenneth Threadgill (1909- 1987) did much more than help a teenaged Janis Joplin discover herself

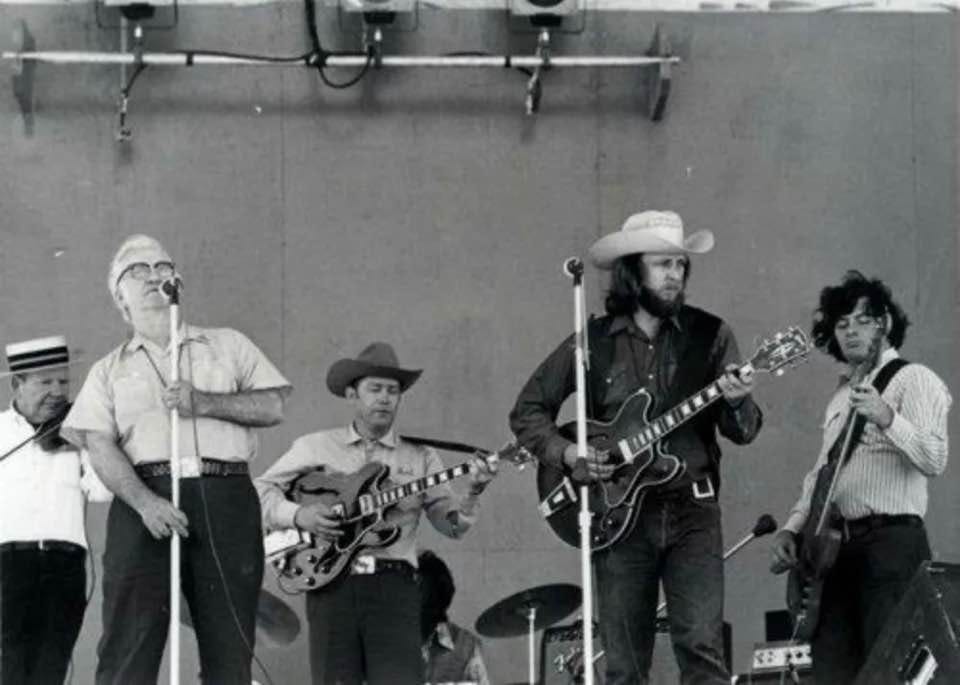

Willie Nelson famously brought the rednecks and the hippies together in musical affinity when he debuted at the Armadillo World Headquarters in August 1972. But Kenneth Threadgill laid the groundwork for the co-mingling of the species the previous seven years when he played every Saturday night at the Split Rail, a country beer joint on South Lamar. He was a hardcore country singer, a throwback to Jimmie Rodgers, but he often had longhairs in his band. “Where the heads meet the necks” was the Rail’s unofficial slogan.

This yodeler with the beer belly had counterculture bona fides for giving their queen Janis Joplin her breakthrough at his fillin’ station/ beer joint on North Lamar in 1962. When they passed the hat at Threadgill’s Wednesday night’s hootenannies, that was the first money the uncouth, unkempt country blues belter from Port Arthur had ever made with her voice.

But more importantly, the tavern owner’s enthusiasm for how she put a song across was the validation she so desperately needed. What set Threadgill apart from the fellow UT students who applauded Janis at the “folk sings” in reserved rooms at UT’s Texas Union, was that he had seen it all. He knew Rodgers, “the Singing Brakeman,” in the ‘20s, had been hosting music since the ‘30s, and sang with local country bands in the ‘40’s and ‘50s. Everybody knew the story of when Threadgill was the impromptu opener for Hank Williams at Dessau Hall in 1948. The headliner looked to be a no-show, so Dessau owner Hallie Price plucked a noted local country singer from the audience to cover for him. Backed by the house band, Threadgill was singing “Lovesick Blues” when Hank Williams walked in.

Threadgill always celebrated his Sept. 12, 1909 birth at the Split Rail, so the “KT Jubilee” in July 1970 was a “thanks for everything” tribute not tied to the calendar. A crowd of about 500 was expected at the BRW Party Barn in Oak Hill, with an advertised lineup of Mance Lipscomb, Shiva’s Head Band and Threadgill’s Hootenanny Hoots. But 5,000 showed up after Joplin checked into the Holiday Inn on Town Lake the night before, flying in from Hawaii with leis. Janis didn’t do incognito.

Joplin sang two songs at the Jubilee by her good friend Kris Kristofferson, “who’s gonna be famous, I give him a year,” she said in introducing “Me and Bobby McGee.” She also sang “Sunday Morning Coming Down” for her mentor, backed by Julie Paul and Chuck Joyce, the married couple who steered her Waller Creek Boys (with Lanny Wiggins and Powell St. John) to 6416 N. Lamar in ‘62. Janis recorded “Bobby McGee” just a few days before she died of a heroin overdose in October 1970. It became her first and only #1 single in 1971.

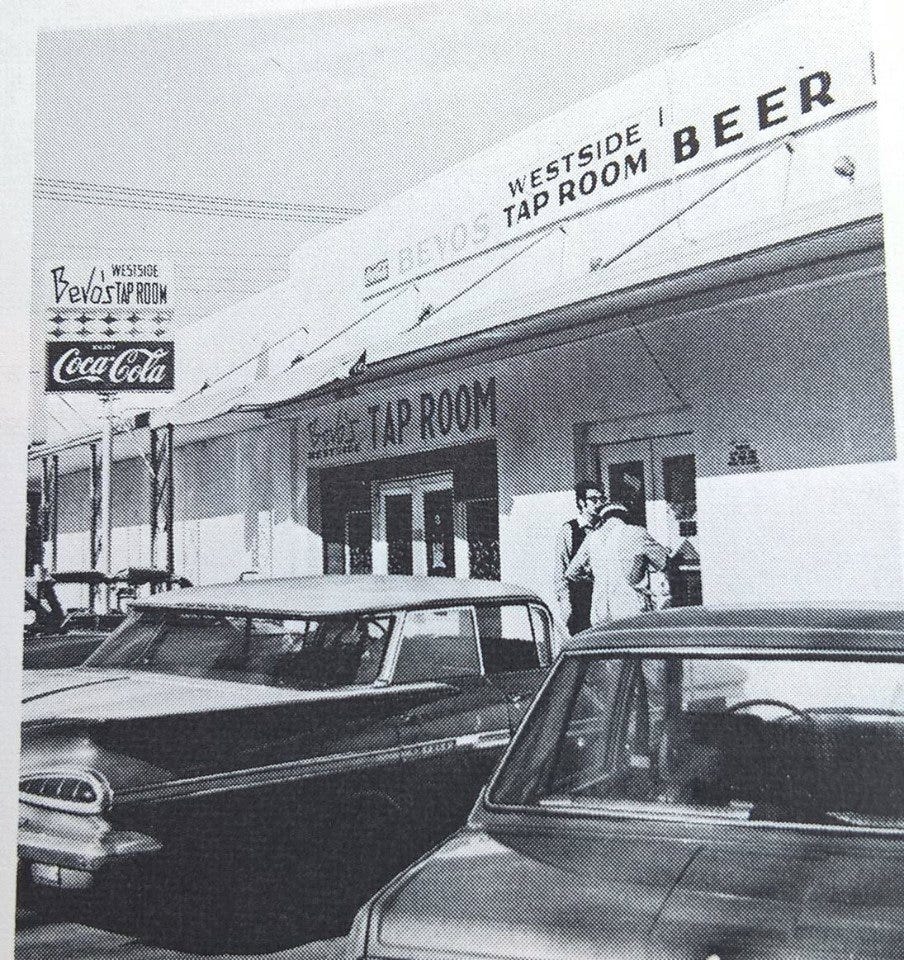

After Janis died, Kristofferson followed up on her promise to get Kenneth Threadgill a record deal. He heard him yodel at Darrell Royal’s afterparty for 1972’s Dripping Springs Reunion, then flew Threadgill and the Joyces to Nashville the next month for four sessions at Jack Clement’s recording studio. Using royalties from “Bobby McGee,” which fulfilled Joplin’s prediction of stardom for its writer, Kristofferson paid for everything. But apparently nobody wanted Jimmie Rodgers covers in ‘72 and the sessions were never released. Threadgill’s only album, 1981’s Silver-Haired Daddy on Armadillo Records, was credited to his Velvet Cowpasture band, which played regularly at Bevo’s Westside Tap Room at 24th and Rio Grande, Spellman’s on West Fifth and the pre-expansion Back Room. Freda and the Firedogs took over Sundays at the Rail in 1972.

Threadgill rarely performed outside the Austin area, but he did three nights in 1972 at Mother Blues in Dallas, as former Austin club owner Bill Simonson (11th Door, Id Coffeehouse) experimented with country. The crowd showed up in big numbers, so the progressive yodeler was booked for a five-night stand.

But Threadgill never made any real money in music until 1980’s Honeysuckle Rose, which he appeared in with Willie Nelson. Threadgill was not really a songwriter but he got an original, “Coming Back to Texas,” on the double-platinum soundtrack.

This son of a roving Pentecostal preacher is remembered less for sheer talent than for the community he nurtured with his kindness, and the example of doing whatever you can to make life better for others, and then yourself.

John Kenneth Threadgill was born in Hunt County just outside of Greenville, the 9th of 11 kids. His family came to Austin in 1923 when he was 14. After graduating from Austin High in 1928, Threadgill moved to Beaumont, where his father had led a Church of the Nazarene for four years before Austin. Beaumont was where he first heard “the father of country music” and started to sing like Jimmie Rodgers instead of Al Jolson.

Back in Austin, he worked at a Gulf Station on the Dallas Highway (North Lamar) and made a little extra selling $5 copies of the Austin American morning paper, wrapped around bootleg liquor. Eventually he bought the gas station and when Prohibition ended in 1933, Threadgill waited in line overnight to get the first license to sell beer in Travis County. The fillin’ station became Threadgill’s Tavern, which was closed during WWII.

Kenneth got a job as a welder for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, repairing bridges and other structures on area bases, then worked at the magnesium plant where Balcones Research Center is now. He wanted to fight in the war, but kept getting 90-day deferments. He was too valuable to draft.

After the war, Threadgill’s gas station/ beer joint reopened and stayed open, 24 hours a day. “I didn’t have a key for nine years,” he told the American-Statesman in a 1970 profile that provides much of the information here.

After the clubs closed at midnight, or 1 a.m. on weekends, the party would end up at Threadgill’s. “Pop Wheeler would come by with his bass, Mildred Womack would sit at the piano, and Joe Ramon on fiddle,” Threadgill said of the afterhours jams that would sometimes last until 5 a.m. Threadgill had his own string band at the time with Shorty Zeiger, Ole Peterson, and Herman Thompson, the one-legged fiddler.

Threadgill’s favorite Austin band of that era was Dolores and the Bluebonnet Boys, who “did more to teach me about music than anybody I’ve ever known.” Dolores and drummer husband Lee Farriss went right home after gigs, so Threadgill went to them, often sitting in at the Skyline, just up the Dallas Highway.

Kenneth and wife Mildred started keeping business hours in the mid-’50s, but the Saturday night jam sessions were getting so crowded that they moved to midweek. At 9 o’clock every Wednesday night, Threadgill would come from around the bar, still wearing his apron, and yodel a short set that would end with a crowd-pleasing jig. Threadgill otherwise forbade dancing, lest he be hit with a dancehall tax.

There was always a big groan at last call, but Threadgill would say, “we don’t make the laws, we just try to get along with them.” On one particularly chaotic Wednesday night, Threadgill was told he had a lot of patience. “Thanks,” he answered, “but I prefer to call them customers.”

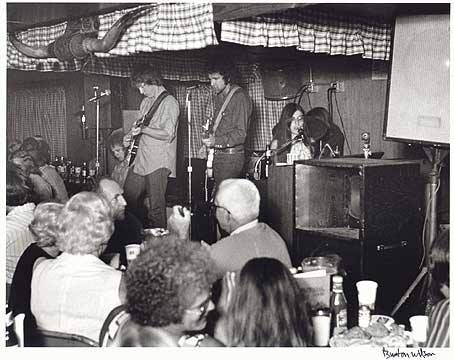

Threadgill and his Hootenanny Hoots wanted to see how good they really were, outside the “home cooking” embrace of the Tavern, so Zeiger and Bill Neely, the great white country bluesman, approached Bob Bass at the Split Rail in 1965. He gave them Sundays.

In the ‘50s, the Rail was a drive-in at 303 S. Lamar, known for great onion rings and overdone steaks. Destroyed by a fire in 1960, the restaurant moved a block north to 217 S. Lamar, across the street from the Pitch N’ Putt. It was more of a hangout with cheap pitchers than a music venue, though such honky tonk singers as Roger Beck and Barney Tall played weekends. “It was just a couple picnic tables and an old shed,” is how Threadgill described the joint, where good ol’ boys came to relax after a day of chopping cedar in what would later be called West Lake Hills. The Joyces wrote “Split Rail Inn” about the club’s inclusionary mindset. “Are you straight, are you hippie, are you Klan?” goes the chorus.

With his smattering of pot-smoking, war-protesting fans growing into a throng, the man with the silver bushy sideburns was the link between Barney Tall and Marcia Ball. What KT started on Sundays at the Split Rail, Freda (Marcia) and the Firedogs turned into a local sensation. If you didn’t get there a couple hours early, you wouldn’t get in. “I’d go into the Split Rail and sing ‘Is Anybody Goin’ to San Antone’ and everybody would flip out,” regular Freda guest Doug Sahm told Ed Ward of the Statesman. “There was all this love that I needed.”

That was the legacy of Kenneth Threadgill, who passed away in March 1987, the month that South by Southwest debuted. It marked the end of one era in Austin music and the start of another.

EXTRA! EXTRA! Read all about the “Split Rail 16,” former employees who got beat up on their picket line in 1977 by the good ol’ boys

I seem to remember reading a story about the Joyce's that involved the late great Denny Freeman. Oh, to have been around back then, with the experience to know who to watch....but if I was, I'd be really old now!

Great job telling these stories that need to be preserved, before everyone who knew them passes on.