“Some soap box where Cody sings the blues/ With eyes closed as he strums and taps his boots/ Locked inside the chamber of his moods/ The only place he’s ever known” - Bill Wilson, “The Ballad of Cody” from the 1973 LP Ever Changing Minstrel.

Cody Hubach was a fixture on the ‘60s folk/blues scene in Austin, then helped christen the One Knite stage in the ‘70s and the Austin Outhouse in the ‘80s. But the only time the Statesman profiled “the Manchaca Toubadour” was as a sculptor who sold a piece to Luci Johnson for a Christmas gift to Tricia Nixon.

Making art and playing music came from the same place of inspiration for Hubach, who built a cabin for his family and lived off the land in the wilds off Slaughter Lane.

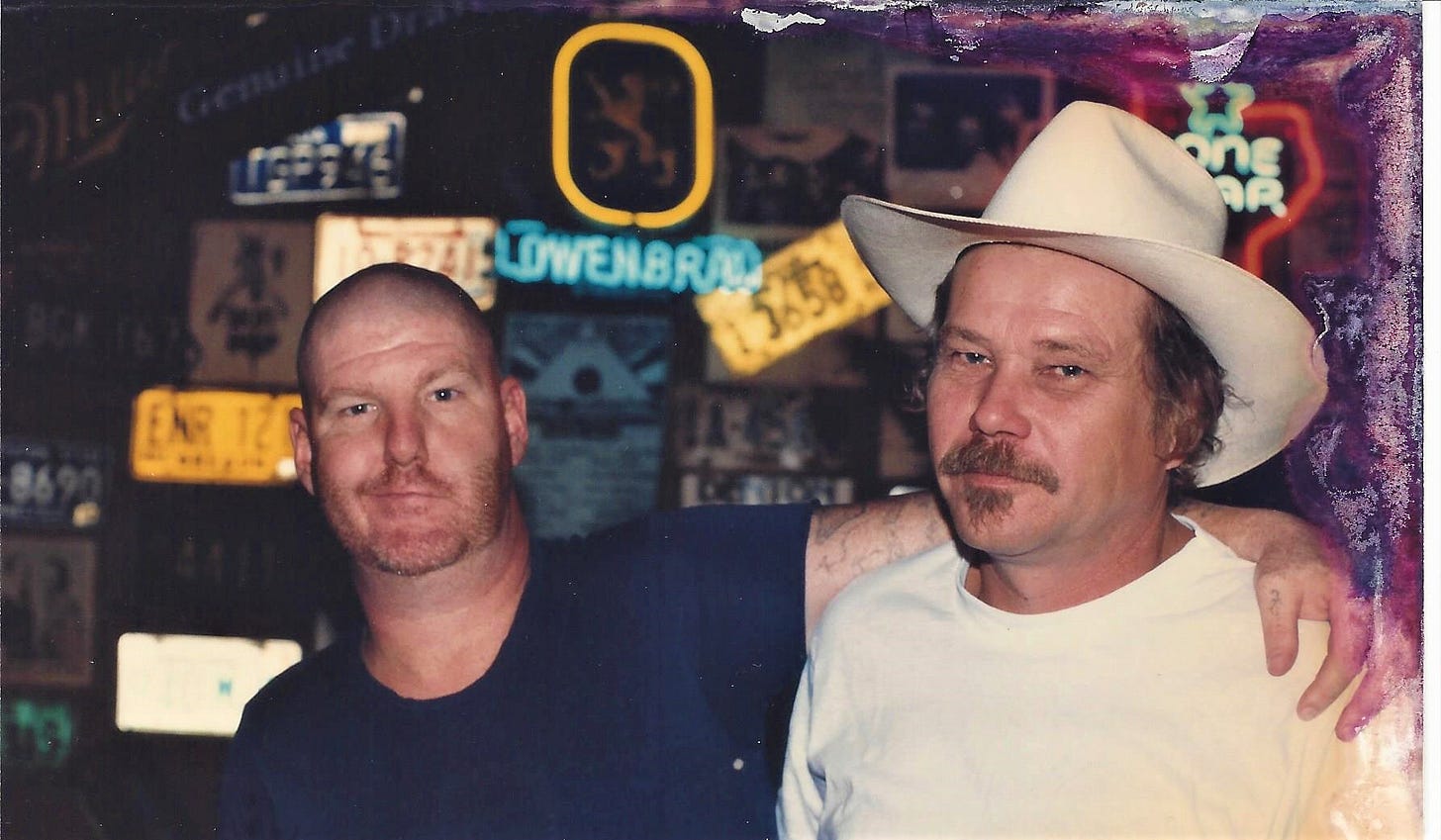

“The word that best describes Cody Hubach is ‘independent,’” said John Casner, who produced I Got the Blues, a just-released album Hubach recorded in 1999, a few months after being diagnosed with the cancer that would take him four years later. “He did things his own way.” A cowboy to the core.

The album not only showcases Hubach’s soulful vocals and bluesy guitar groove, but pays tribute to Bill Wilson, who penned five of the best songs, including “Skid Row Rodeo,” “Dragon Fly Charade” and “Black Cat Blues.” Wilson died of a heart attack in 1993, at age 47.

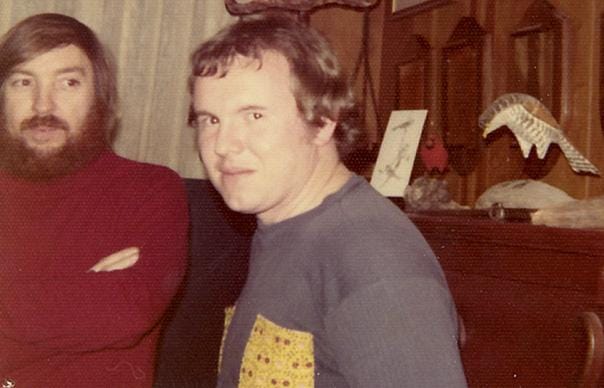

Wilson was an airman at Bergstrom AFB when he met Hubach on the local folk circuit in late ‘68. Cody became a friend of Bill W., with the pair covering each other’s songs and hanging out together. They played every week at the Red Lion, in the former W. Sixth St. location of the Turf Lounge, until Wilson’s military bid was up in 1970 and he returned to his native Indiana. “Bill played some Glen Campbell songs, as well as some of his own,” said Red Lion owner John Meadows, who played banjo and served as emcee. A 13-year-old Nanci Griffith performed for the first time at the Red Lion after it opened in 1966.

“Cody learned a lot about songwriting from Bill,” said Tom Evans, who rode motorcyles with the pair on off-road “Enduro” contests. “We thought he was a genius.” Hubach was in a failing marriage to a local stage actress and working as a welder for the Blue Bird school bus company when songwriting became a necessary passion.

Hubach knew everybody on the scene and did what he could to help his new G.I. friend, who’d lost half his index finger on his right hand in a bike chain mishap, and had to relearn how to pick his guitar. When Bill Josey Sr. recorded Hubach for his Sonobeat label in 1969, the singing welder suggested giving Wilson a shot in the studio. Josey had just started his Sonosong publishing company, so he recorded Wilson’s originals as demos to pitch to other artists, but nothing came of it. The Joseys (Bill Jr. went by “Rim Kelly” on KAZZ-FM) had good intentions, but not much clout outside Travis County. The Hubach single was never released, nor was a 1972 album for Sonobeat.

In 1973, Wilson drove from Bloomington, IN to Nashville with the home address of producer Bob Johnston, whose credits include Blonde On Blonde, Johnny Cash’s At Folsom Prison, Sounds of Silence, and the first few Michael Murphey LPs, among many more. A knock on the kitchen door irritated Johnston, who said “this is not the way to get a fuckin’ record deal.” Just one song, sir, and I’ll be on my way. Wilson ended up playing 12.

As the story goes, Johnston started calling up the session players he’d used for Dylan’s Nashville Skyline, including Pete Drake on pedal steel, Kenny Buttrey on drums, Charley McCoy on harmonica and Charlie Daniels on bass. That very night they went into Ray Stevens’ Sound Lab Studios and, with Jerry Reed on guitar and Cissy Houston on backup vocals, bashed out the entirety of Ever Changing Minstrel. Guitarist Mac Gayden’s nasty Southern slide guitar predates the Lynyrd Skynyrd debut coming later that year. This all happened in one day, and it must’ve seemed a dream to Wilson because he could never find a copy of the album anywhere. It barely came out on Columbia offshoot Windfall Records in 1973. Bill Wilson never saw Bob Johnston again.

Forty years later, record collector Josh Rosenthal found a copy of Minstrel in the quarter bin of a Berkeley record store and bought it, based on Johnston’s production credit. Rosenthal flipped over this nascent country rock and ended up licensing the forgotten LP and reissuing it on his Tompkins Square label.

Listen to “To Rebecca” from Wilson’s Ever Changing Minstrel.

It’s not known how closely Wilson and Hubach kept in touch through the years, but “Cody talked about him all the time,” when recording I Got the Blues, said Casner.

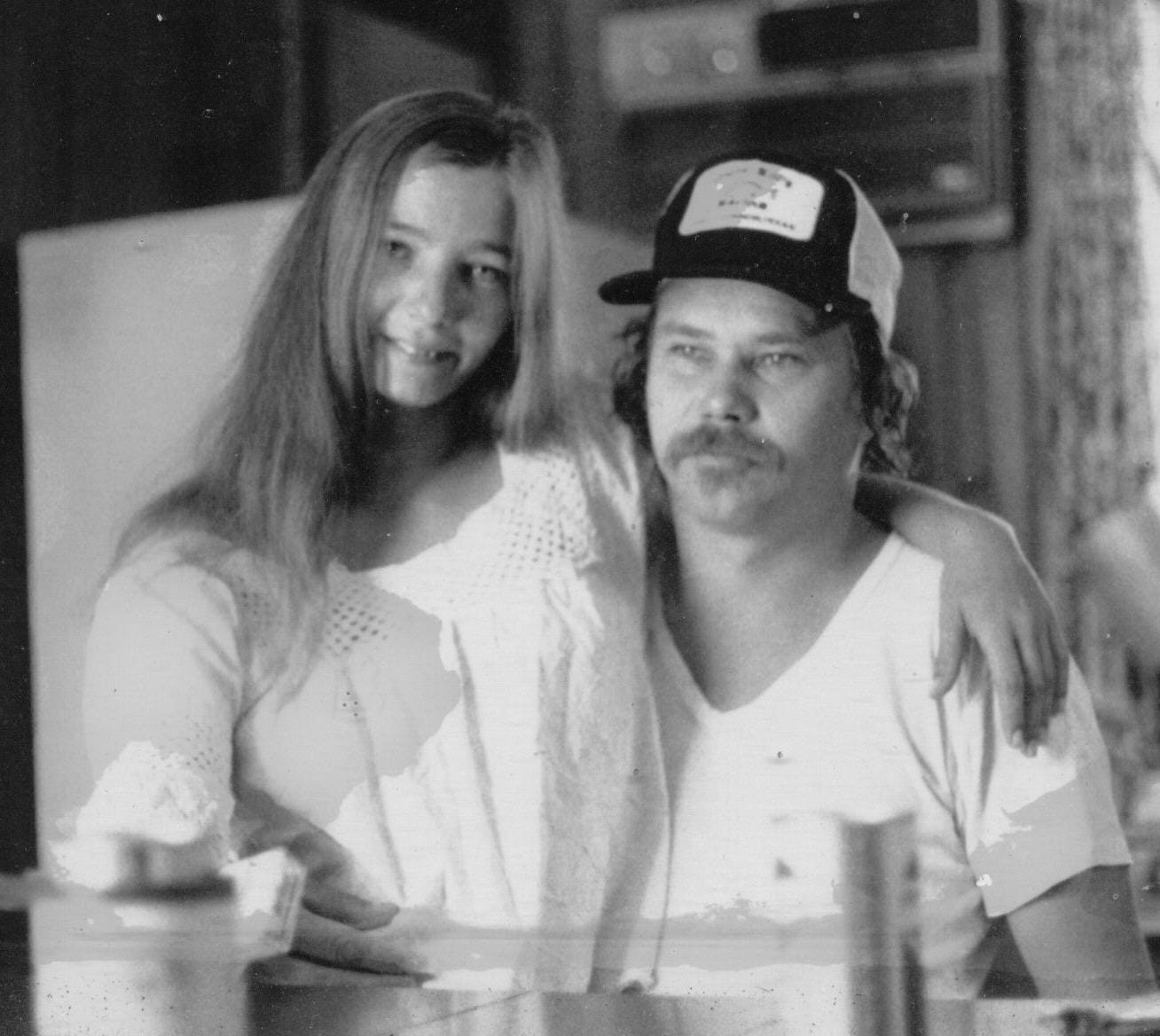

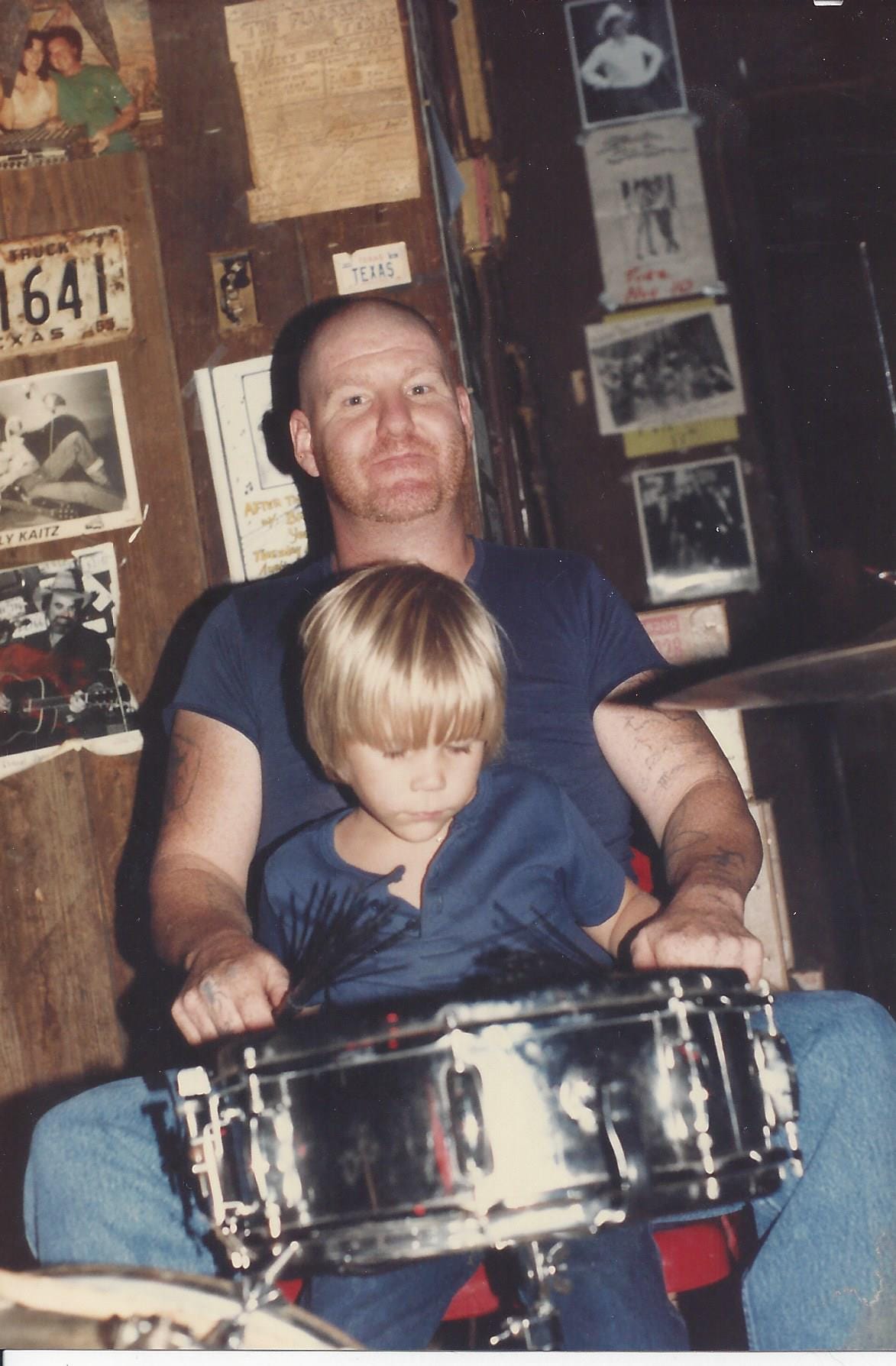

In the ‘70s, Cody met another artist named Cathy and they got married. He had his metal shop next to the cabin and eventually passed on the welding art to the couple’s only son Buck Hubach, whose Warbach lighting design company with Nathan Warner is getting well-known for large-scale illuminated sculptures.

After his favorite venues, the One Knite, Split Rail and Spellman’s closed, Cody Hubach found a new musical home at the Bentwood Tavern at 3510 Guadalupe. This was a classic neighborhood bar, with darts and shuffleboard and softball teams, but manager Chuck Lamb and harmonica-playing bartender Ed Bradfield started booking music around 1979. Besides Cody, regulars included Blaze Foley, Jubal Clark, Pat Mears, Rich Minus, Calvin Russell, Lost John Casner and Townes Van Zandt.

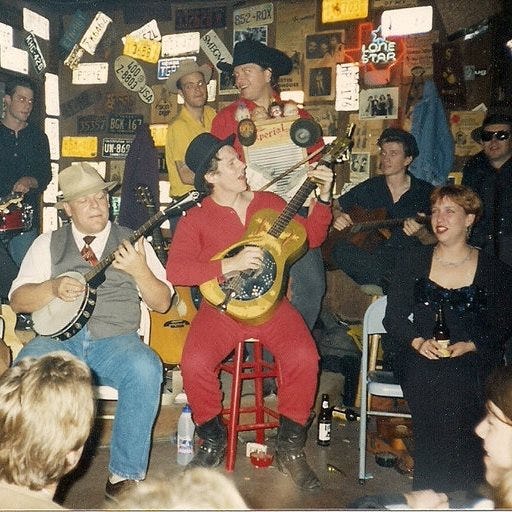

That bunch of boozey musical poets came with the place when Lamb bought the license plate-plastered dive in 1981 and changed the name to the Austin Outhouse. I lived two blocks from the Hole In the Wall, so I rarely made the eight-block trek to the Outhouse in the ‘80s, but when I did go to see Herman the German or Pocket FishRmen it was as crazy as any bar in town. The Outhouse was a shithole, but the best kind.

For a stamp of extra weirdness, 3510 was the new homebase of Curly Thompson, Austin’s #1 musical savant, who was a fantastic drummer, played blues harp with just his hands and sang like Bon Scott when he wanted to. A strange cat, but truly loved by everyone.

“I loved those years, good and bad,” said Lamb. “Music every night, good and bad. People you probably know, many you never heard of. It was real. I was sad the night we turned out the lights.”

The club had been bailed out by benefits- most notably a Timbuk 3 show in Jan. ‘89 that paid back rent on the verge of eviction. A week after that jubilant celebration, Outhouse regular Blaze Foley was shot to death by the son of a friend. Cody Hubach was among those who played an emotional show to raise money for Blaze’s funeral. There were close friends.

Here’s Cody doing a Bill Wilson song at the Blaze Memorial 2/26/89 at the Outhouse.

Hubach’s final public performance was at City Hall Oct. 24, 2002, “Cody Hubach Day.” He passed away Feb. 7, 2003 at age 58.

Perhaps coincidentally, perhaps not, the musical focus at the Outhouse gradually changed after Foley’s death to more indie rock band. It became the new Beach, north of campus, with such bands as Happy Family, ST37, T.I., the Horsies, Coz the Shroom, Go Dog Go, Brompton’s Cocktail and so on.

Asylum Street Spankers packed the place every Wednesday with their old-time acoustic music, and zany antics. First Wednesday was Pajama Night- which some lovelies took as Lingerie Night- for an only-in-Austin scene. “At the end of the set we’d say, ‘now let’s go break into Barton Springs and go swimming’ and half the crowd would come with us,” recalled Forsyth.

Most of the bands weren’t that interesting, so people would go out on the patio and smoke pot. Then the bands would sound better so they came back inside.

“When you saw a great show at the Outhouse, you walked out feeling like you’d stolen something and gotten away with it,” said head Spanker Forsyth, who played the Outhouse until Flamingo Automotive bought the property for an expansion in 1995.

Cody Hubach also played the Outhouse until the very end. It was a stage of zero status, but where he and his friends could always do their own thing.

The CD release party for I Got the Blues by Cody Hubach is Sunday April 3 at Giddy Ups on Menchaca Road from 2- 6 p.m.

MORE READING:

My husband, Jay White, knew Cody well, played music with him often and spent time at the cabin. He remembers him fondly.

Another great gem!!!