A Match Made In Limbo

An escape to S.F. and love in the Windy City: the Corky Chronicles Continue

Stymied Austinites have been moving to the Bay Area since Janis Joplin and Chet Helms hitchhiked there in late ’62, with Janis returning to become a star in ’66. As beatniks became hippies, Haight Ashbury was ground zero for the counterculture explosion, and from the Lone Star State migrated Doug Sahm, Steve Miller, 13th Floor Elevators, Conqueroo, Powell St. John, Boz Scaggs and more. “Liberal” Austin was still Texas, where two joints could get you five years, and long hair was grounds for a good ol’ boy pummeling.

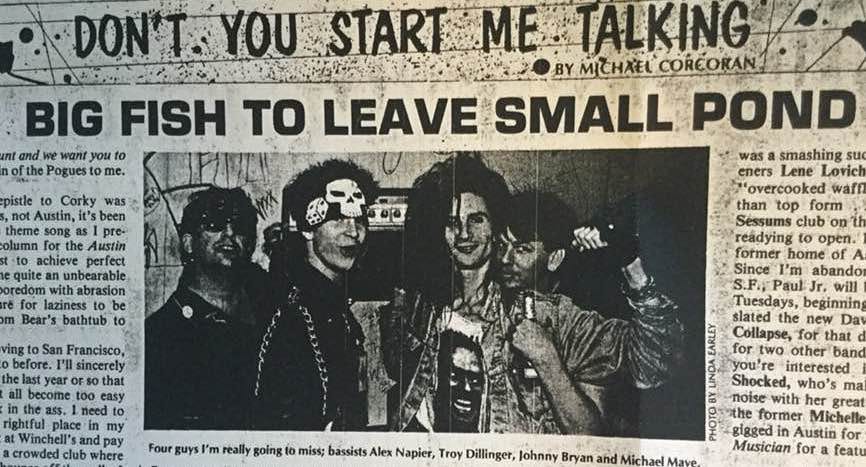

Sometimes you just need to start over. I moved to San Francisco in June 1988, right after my Pogues fiasco, to get away from being Corky, who couldn’t write a things-to-do list without doing a bump. My farewell “Don’t You Start Me Talking” column in the Austin Chronicle was written without performance enhancing drugs, so it was pretty straight. I needed something to make readers go wow, so I dug up a note I typed a month earlier for when they found the body.

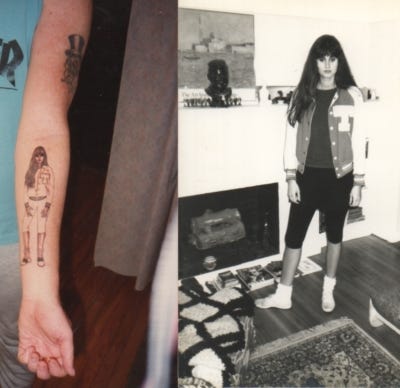

“It’s 2 a.m. and I’m dying. My heart is pounding like an offbeat engine and my arms and legs are numb. I would go to the emergency room, but I did that last week. Just tired of it all. The problem is not methamphetamine. That’s not what killed me. It was the realization that a laugh dies as soon as it stops. I’ve got a bunch of tattoos because they’re the only things that are permanent in my life. Everything else only lasts for the moment, then dies like I am now. I don’t care. I think I must want to die because in the past two weeks I’ve had three or four episodes like I’m having now. I can’t take speed any more. I know that and I still do. Stupidity is grounds for death and I’m guilty. I just don’t give a fuck anymore. I’m tired of coming down from the high and being let down from the straight. I’m tired of depression that starts a minute after ecstacy. I’m sick of the way I can be an asshole even when I’m aware that I am. I’m tired of bills that need to be paid now and checks that come whenever they damn well feel like it. I don’t want to be a character anymore. I want to be alone. I died a junkie, a drug addict, a person who didn’t have what it takes biologically. I died a lazy son-of-a-bitch, but while I lived I was a good brother, a good friend. I cried at sad movies and loved to read trashy magazines. I was proud of what I had written on speed. I’d rather die than be a boring writer, and so I have. My friends and family won’t understand. They’ll say what a waste- he had so much going for him. They just don’t know. Ever since I was 12 years old I dreamed it would be like it is now. I’m finally becoming a successful writer, but I hate to write. Speed is what did it for me. It made me reach my potential which is all I ever wanted out of life.”

I didn’t die. I quit doing speed. In San Francisco, me and Brent and Scott rented the top floor of a big house in the Mission, and I got a $100 a week job writing a music column for the East Bay Express in Berkeley. But I was basically retyping my old Chronicle riffs (oh, the pre-Internet years!) and adding music news on Bay Area favorites like Pebbles, pre-stardom MC Hammer, Mr. T Experience, Chris Isaak, Beatnigs and Doyle Bramhall II’s band Texas. I missed Austin a lot more than I thought I would, and went out of my way to see any band from back home. I lived on Mission burritos the size of Pringles cans, and hung out at the Chatterbox, a glam bar in homage to the New York Dolls. SF was a cool city of neighborhoods that had their own identities, but it’s ultimately a bullshit town, the Boston of the West Coast.

After about a month, I received a letter from a woman from Chicago who was moved by my “I’m dying” column, and confessed to a “monster crush” when she lived in Austin. We had only met once, she said, just briefly at Woodshock in the summer of 1985, but I knew exactly who she was- a tall, beautiful woman with dark eyes and Italian hair- who I was convinced had been a hallucination. We wrote letters back and forth for a month, and I looked for a way to visit Chicago, when I was thrilled to receive an advance cassette of a new Ministry album, A Mind Is a Terrible Thing to Taste. I didn’t care about the music as much as the band’s homebase of Chicago. I pitched a feature in Spin and got the assignment.

Even though I was poor, I lived a rich life as a music critic in the late ‘80s. Flush with all that CD money, the labels paid for everything when you wrote magazine articles on their acts. If you went out to see one of their new bands, you’d get a voucher that let you drink for free. They’d also put you up in nice hotels, but Warner Brothers only had to only pay for airfare to Chicago. I changed my return flight so I could stay with Erica another five glorious days.

One night we split up, as she went to a dropping-out party for one of her friends in law school and I went to see Richard Thompson at the Park West. Now, I’d heard “Wall of Death” from the Shoot Out the Lights LP many times, but on this night it was just me and that song.

You can waste your time on the other rides

This is the nearest to being alive

Oh let me take my chances on the wall of death

Nike would boil down the essence of that song as “just do it.” I came back to San Fran only to get my shit.

I’ve got a bunch of tattoos because they’re the only things that are permanent in my life.

We had a great year, then an OK year, and then I was living alone in a $425 box on Roscoe Street that was the exact midpoint between el stops, so I got the train going by at its fastest and loudest, plus I had to walk about 8 blocks in the freezing cold to catch one. The only good thing about that location was that it was on the way home for Sue Miller, so she’d give me a ride after a night at Lounge Ax, which was not quite yet the coolest rock dive in Chicago, though one bartender’s sister was in Smashing Pumpkins and another was in Uncle Tupelo, but not the main guy. Sue and her partner Julia booked a lot of acts from Austin, who knew to bring a case of Shiner Bock, the beer that SXSW made famous.

Sue and Julia thought I’d made up having a girlfriend because Erica never went to Lounge Ax with me, and I was there three times a week. She didn’t go to any rock clubs. Having come of age at Raul’s while attending UT, that scene couldn’t be topped in her mind, and going clubbing ten years later just made her miss her friends. Her favorite thing was going to movies, which I’m not into because I have a thing about people eating behind me. We once counted every movie we’d been to together, then every music club and the score was 3-2, movies, after three years!

You could float an aircraft carrier through the moat of our differences, but I think the main reason it didn’t work out was that we just couldn’t live up to the fairytale. Reality kicks my ass once again.

She said she would never marry me unless I quit drinking, but the longest I ever stopped was for a month, January 1990. I bet her $150 I’d never drink again, so that Budweiser quart ended up costing me $152.50. A couple years later I went to a drug and alcohol rehab place in Phoenix for Family Week support of a sibling, and it was a gut-wrenching experience. One of the exercises was to write a letter to someone from your past and mine apologized to Erica for being such a loser lush. Then you burned your letter. I was followed by a guy who started crying even before he read his letter, which began “Dear little Vietnamese girl.” And here I was getting choked up about making Erica pull over so I could buy a 40-oz. for the ride home.

I didn’t leave that relationship without anything. Though we haven’t spoken in almost 30 years, Erica still cracks me up weekly. She was so damn funny with her cast of characters, like “Pony Girl,” a hot, dumb cowgirl she invented when we drove through an East Texas town on a Christmas visit home. “I’m from Splendora,” she’d proudly announce. “It’s in Texas.” (OK, I’m seeing that the funny part was the way she said it.) “Grandma” would come out, pointing a crooked finger, whenever I needed scolding, and then there was “Shy Girl,” pathologically uncomfortable in social situations, who would only communicate by whispering in my ear. “Sometimessss,” she’d say with a light hiss, then pause and repeat, “Sometimessss I go to a party and I want to go home.”

She had an unnamed persona who would point out my qualities with an index finger on my cheek. “You’re a blue-eyed sweet pea,” she’d say, with a tap. There’d be another compliment or two, and then, “but you’re lazy” and her finger would trace down my face in disappointment. “You’re so lazy!” I was also too dumb to realize that her characters were speaking to me, in a non-confrontational manner, on how I needed to improve, as boyfriend and human.

When I finally sat down to write about my time in Chicago (Nov. ‘88- Jan. ’92), I made up a bunch of characters based on composites and juiced up the plot a bit. But much of this fiction actually happened.

You can read it here: All That’s Left Is Everything.

Perhaps the greatest lesson I learned from my time with E was the beauty of the McBride. In the summer of ‘89, she beat out hundreds of other law students for a well-paid summer internship at one of Chicago’s big law firms McBride Something & Something. We met at Bennigan’s near the Art Institute after her first day and she was miserable. “I hate it.” It took her just a couple hours in required nylon stockings to realize that this was not why she wanted to become a lawyer. “Just quit, then,” I said. She shook her head, like I can't do that, and thought about it for a long minute. “I’m gonna quit!” she said with a broad smile, then crushed that cheeseburger.

A week or so later we went to one of those Bob Dylan concerts where you realize, “Omigod, he was just singing, ‘Just Like a Woman’." “Let’s McBride,” I whispered in her ear and we were soon skipping down Michigan Avenue. “McBride” became our code for bailing on something, like an invitation to a stuffy dinner party or a speech that’s going nowhere. She did it so often I called her Lady McBride. (Not really, I just thought of that.)

There’s nothing wrong with quitting something that's making you miserable. Sometimes "giving up" will take you where you were meant to be. The day after the girlfriend quit the big law firm, she started working for the People’s Law Office, a firm she greatly admired for their handling of police brutality cases. To given an idea of how hardcore the PLO was, the receptionist was Deborah Johnson, who was laying next to Fred Hampton in Dec. ‘69 when he was assassinated by Chicago police. This radical law office became her life for awhile. She married one of the founding partners and they raised a family. She remembers my birthday every year, or, at least, Facebook reminds her, but there’s no desire by either of us to reconnect. That time of our lives has passed, like Raul’s.

I ended up going back to Texas in Jan. ‘92 to take a job as country music critic with the Dallas Morning News. I would have one good year there before falling head-over-heels again and marrying the wrong person. I’m not ready to write about that yet, especially since she’s become one of my dearest friends, but let’s say “Wall of Death” took on a dire new meaning.

There's something that I like in hearing the honest details of a your life. Keep it up.

More great writing