The Calvin Russell Story

“Austin in the ’60s was dirty, nasty, hip and dangerous all at the same time”

Singer-songwriter Calvin Russell’s story was one for the movies, an ex-con toiling in obscurity in Austin dives before a homemade cassette made him a star in Europe. The Townes Van Zandt protege with the rugged features and signature hobo hat passed away April 2011 at his home in Garfield, after a battle with liver cancer. He was 62.

During his early ‘90s heyday in France, where he was considered a harder rocking, Texas version of Tom Waits, Russell and his band took home as much as $15,000 a night, and gave their fans their money’s worth, playing three hour sets without a break. After shows they often received a Hell’s Angels escort back to the hotel. “They wanted to rock and, boy, we gave it to ‘em,” Russell told me in 2005. His band featured the underrated Gary Craft on guitar.

Russell’s unlikely career windfall came after a party for musician Ike Ritter in South Austin in 1989. Ritter’s friend Charlie Sexton was expected to attend, so, hoping the rising star would cover one of his songs, Russell made a demo tape and brought it to the party. But before he could get it in Sexton’s hands, French label owner Patrick Mathe asked for a tape after Russell performed at the party. Russell had made only one copy.

Four months later, the singer whose real name was Calvert Russell Kosler, received a call from Paris. “You have a heet,” Mathe said, explaining that the tape, entitled A Crack In Time, was released to great acclaim. It went on to sell 100,000 copies in Europe. After Russell was shown performing on a commercial for Swiss Oil during the 1994 World Cup, he couldn’t walk around Paris or Amsterdam or Berlin without attracting a crowd.

“They really loved the hat,” Russell said. “That’s how they knew it was me.” Russell had been given a felt cowboy hat by a drunken patron at some Texas dive, but because he didn’t want to hear Merle Haggard requests all night, Russell cut around the brim to create the cartoony porkpie that would define his image as a trouble-tossed, yet tender troubadour. Russell’s look was not a pose, but the product of a hard life. He started writing songs as an 18-year-old serving time in Huntsville on forgery and marijuana possession charges. His earliest songwriting inspiration was fellow prisoner Shotgun McAdams, a rhyme master who got his nickname robbing Safeways with a shotgun.

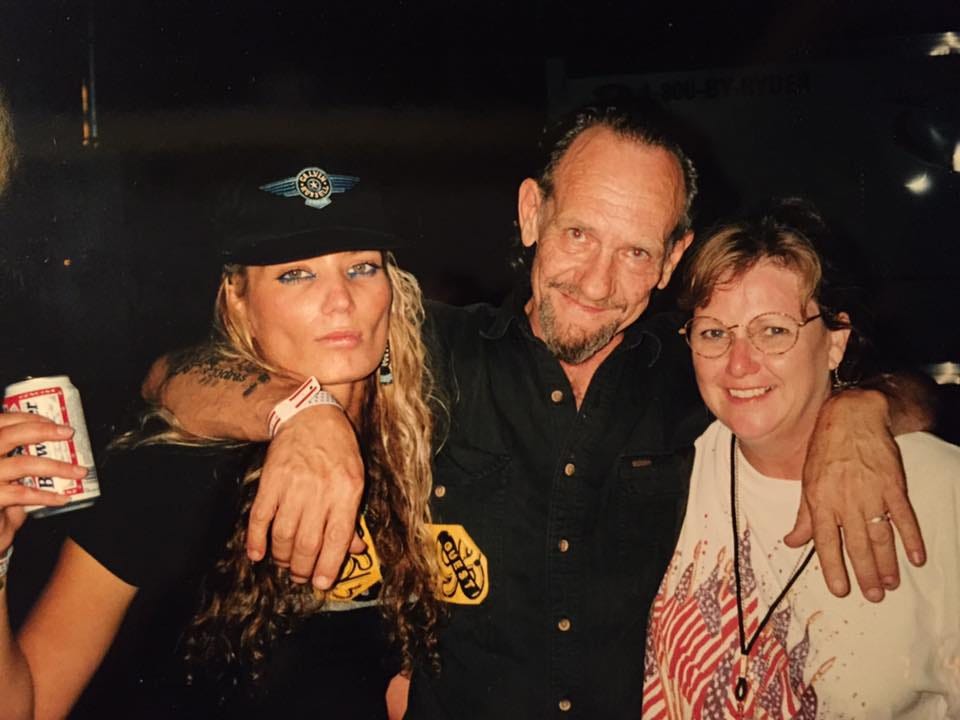

Russell didn’t spend the entire late ‘90s/ early ‘00s in Europe just because he was making good money. Russell was sweating a 1995 conviction for possession of cocaine- busted doing bumps in an alley off Red River. He eventually received eight years probation on the cocaine charge and was able to return to the Austin area, where he bought 14 acres about 10 miles east of town. He lived with his model-beautiful wife, whom he married when she was 22 and he was 49, and five dogs.

Russell was the fourth child, but the first to not die in infancy, of a cook-owner and his waitress at the Sho-Nuff Cafe on South Lamar Boulevard. The family lived on a dead-end street next to Pete Pistol’s Wrecking Yard; one of Russell’s most vivid childhood memories was the sound of the car wheels on the gravel road when the family moved in the middle of the night to avoid paying back rent. Lucinda Williams, who soaked up everything she could from Austin’s derelict songwriters when she lived here in the late ‘70s, loved that story.

Russell was kept back three times at McCallum High School, then kicked out of school when he showed up at the senior picnic with a six-pack of beer. “I was technically a 10th-grader, but I wanted to party with the kids I came in with,” he said.

“Calvin always had that aura about him that he was tough,” said drummer Leland Waddell, who formed the rhythm section with bassist brother David during Calvin’s European heyday. “Everybody knew he was in prison and all that, but he was really a good guy. He cared about people.”

Russell said he’s lived by an adage passed down from his great-grandmother, a Comanche Indian who lived to be 106. “She told me that everyone had two dogs inside them fighting. There was the good dog, the loving dog and there was the evil, violent dog. The one that won was the one you fed.” (Wellworn saying I heard first from Calvin.)

Uneducated Russell was streetwise at an early age. “Austin in the ’60s was dirty, nasty, hip and dangerous all at the same time,” he said. Russell made his living selling LSD, which was legal until October 1966. His supplier was a successful car dealer in San Antonio who had “turned on, tuned in and dropped out” of the straight life, converting his mansion into a counterculture flophouse.

Another benefactor to the peace and love generation was a wealthy, middle-aged West Austin woman who’d inherited a fortune after her husband’s death and used the money to bankroll recording projects and feed and house a commune on her property. “One day we saw police looking at the back of the house with binoculars and that’s when she said, ‘Let’s move to Mexico.’ “

She bought a 60-passenger yellow school bus, ripped out most of the seats, put in a Lear Jet stereo system and rolled south on Interstate 35 with a group of kids in sleeping bags inside. The bus was stopped at the border, however. “They said something or other wasn’t in order with the bus,” Russell says, “but they also said we had to get haircuts.” While the bus stayed on the U.S. side, Russell and his friends walked over to the Mexican side and met a pot dealer who sold them marijuana for $3 a kilo (2.2 pounds). Russell brought the marijuana back to Austin where he sold it for $10 an ounce in Prince Albert cans. In 1968, high on LSD, Russell used a credit card he says someone had given him to get a room at the Chariot Inn. When he signed the name on the card, he was guilty of forgery and ended up serving 15 months at Huntsville.

“I didn’t think I was going to make it,” Russell says of his stint at hard labor. “I had blisters on my hands, blisters on my neck from the hot sun. The guards were a sorry, sadistic bunch and they’d look for any excuse to whale on you.” He also did nine months in a Mexican prison for dope-smuggling.

When Russell got out, he started frequenting Spellman’s on West Fifth Street and fell in with a hard-livin’ songwriting crowd that included Blaze Foley, Jubal Clark, Pat Mears and Rich Minus. But hearing Townes Van Zandt for the first time, at a song-swapping session at Seymour Washington’s former blacksmith shop in Clarksville, was the true epiphany. “He had this magical use of words,” Russell said. “I shut up around Townes and listened. All my intelligence just went right to him.”

Van Zandt respected this ex-con as a true outlaw and took in “Calvert Russell” — he used his first and middle name on the bill until everyone kept misspelling and mispronouncing it as “Calvin” — as a creative protege. By example, Van Zandt taught Russell to write in complete seclusion and to not play a song until it was finished. “You never saw Townes working on a song.”

After Spellman’s closed the drunken angels moved headquarters to the Austin Outhouse. They played for each other, and not just because the crowd was often elsewhere.

All those guys were more popular in Europe, where tough-life Texans were revered, but Russell was a sensation! So here he was in 1990, boarding a plane for Geneva, Switzerland, ready to play his first European show, solo acoustic, in front of 3,000 fans. “I was the opening act for a rock band, so I didn’t know what to expect, but the crowd loved it,” he said. When he played Lille, France, with a full band a few months later, the audience was 7,000 strong and out of control in its enthusiasm. “I was petrified,” he says. “I was afraid to adjust my amp. I kept waiting for the other shoe to drop.”

While most of his musical associates were mired in alcohol abuse, including Van Zandt, who died of a heart attack at age 52, Russell said he was never really much of a drinker. “Psychedelics and some good herb — those were my things,” he said.

But after a French journalist described Russell as a Jack Daniels-swigging tunesmith in a major feature, big bottles of Jack started showing up backstage before every show. And Russell began partaking. “We liked to play on LSD,” he said, “and when you’re tripping you can drink all the booze in the world and not pass out.” The hangovers got brutal and Russell cut out the hard stuff for an occasional Budweiser.

After his 2003 return to Austin, Calvin’s one night to cut loose was Mondays at the Longbranch Inn on E. 11th. Mine, too. I lived in East Austin near Sam’s BBQ at the time and there was almost no live music in the area. Being able to see a musician of Calvin’s caliber, up close for no cover, had me back every week. Backed by a pickup rhythm section, Calvin mixed in original material with covers, and always got the whole place rockin’ with “Oval Room” by his former running buddy Blaze Foley. Cynthia would grab everyone she knew to come out and dance with her. It was quite a scene.

Sometimes Cynthia’s family would be there partying, too. They owned a trailer on the Russell compound in Garfield and visited often. “Cynthia’s just a village girl who likes simple things, like a clean house and playing host to her family,” Russell told me in 2005.

He met her, his fourth wife, at a festival in the Alps in 1996. “Her daddy was a fan and he got his kids into my music, so they all came back after a show,” he said. “That first night, Cynthia said she wanted to be with me, and I thought, ‘I don’t want to have nothing to do with a woman that beautiful. She’s probably just looking for a big cocaine party.’”

A few nights later, Russell and his band were playing a show in Madrid and bassist Scott Garber said, “Hey, Calvin, there’s that girl from Switzerland.” Cynthia was near the front and afterward came backstage. “I want to be with you,” she reiterated, and this time added, “forever.” The Swiss beauty and the hobo poet were married two years later. They cherished the eight years they spent together in Texas.

Playing a dive on Monday nights in front of a few dozen people would seem a big step down for a rocker who filled arenas, but as long as Cynthia was dancing, the Eastside was Paris.

This is a pretty ambitious video of a Calvin original, directed by Tim Hamblin. Lotsa cool scenes from the Austin Outhouse, with some people you probably know.

Hi there Michael - thanks for remembering a a really wonderful man - I worked with him for 3 years - late nineties - so I can attest to idea that while there was a tough older crowd there (EU) the positive nature of his songs also captured a younger crowd. They were inspired by a man who had been through so much but still saw the world in a positive way.

One note: t’was I who told Calvin it was Cynthia at the bar waiting for us to do Soundcheck at the Chesterfield in Madrid. It was a 2 week gig so it gave them a great time be together at the start of their long love affair. Also year was ‘97

Best,

Scott

That is a longer story …