Uncle Seymour's Clarksville

Retired blacksmith adopted a group of scruffy musicians led by Townes Van Zandt

In the 100 years after 1871, when an emancipated Charles Clark bought two acres in West Austin and sold lots to fellow former slaves, Clarksville was almost all African-American from West Lynn to Exposition. It was a densely-wooded “freedman’s town” of dirt roads and shanties, where the people were self-sufficient- hunting and fishing and growing their own vegetables. To make money, they worked as domestics for the rich white folks of Old Enfield, just a few blocks away.

Clarksville was nearly invisible to the city of Austin, which withheld services to Blacks not living in the designated “Negro District” (via the 1928 masterplan) of East Austin. But that was fine by residents who didn’t mind using an outhouse if it kept them out of the white gaze. They were country folk who wanted to be left alone.

The construction of MoPac Expressway, which began in ‘71, changed all that. As it tore through the tight-knit community, more than 60 Black families were displaced. Some were given as little as $4,500- the appraised value- for their homes, many of which lacked running water or electricity. Clarksville, which didn’t get paved roads until 1975, is today one of Austin’s toniest neighborhoods.

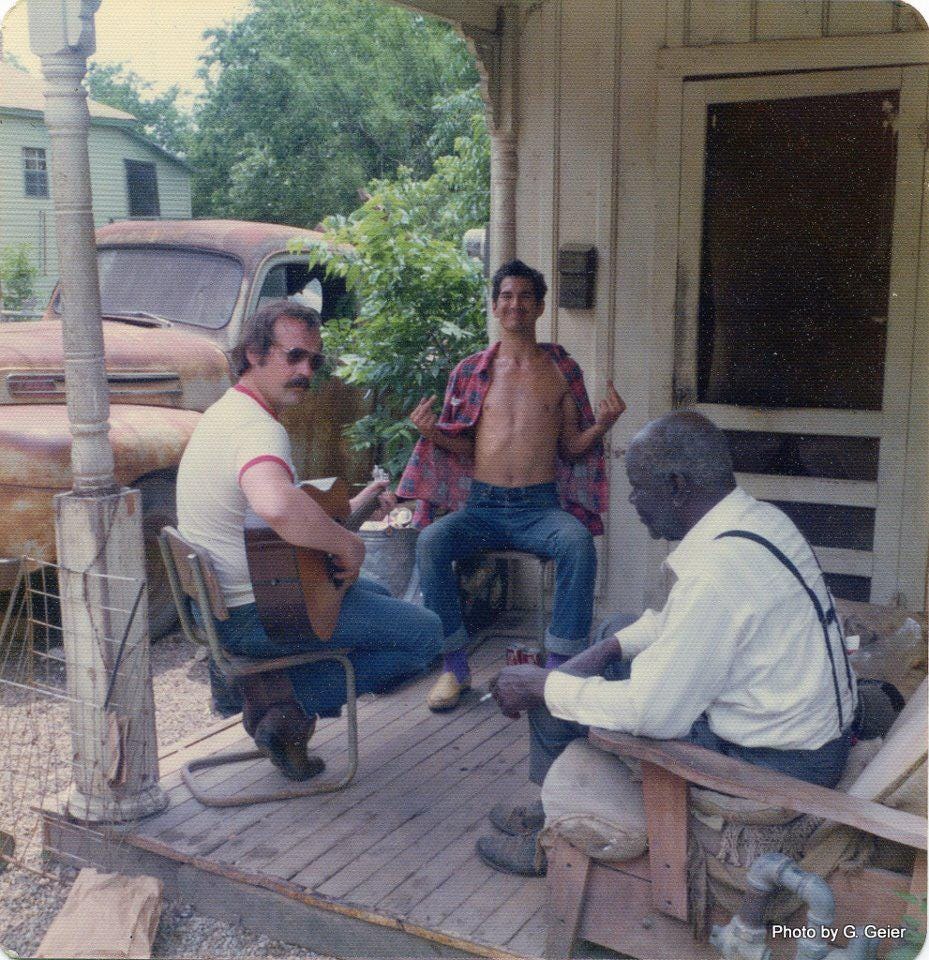

Hippies and musicians integrated Clarksville in the late ‘60s/early ‘70s, when rent was still dirt cheap. Longtime residents looked suspiciously at these longhaired freaks with their guitars and bra-less girlfriends, but they were welcomed by retired blacksmith Seymour Washington, the unofficial mayor of Clarksville. They called the wise, old man, who loved the Bible and his bourbon, “Uncle Seymour.” His front porch, next to a rusted lawn ornament on four wheels, was the gathering place.

Washington “could’ve been a good preacher if he wasn’t a blacksmith,” Richard Dobson wrote in his Gulf Coast Boys memoir. “He got right into it when the spirit moved him.” He sang in the choir of Sweet Home Baptist Church, the community bedrock on the next block, but they wouldn’t let him preach because he drank. But “Unk” used scripture to justify the daily embibing. “People condemn whiskey, but they have no right to,” he told Townes Van Zandt and the documentary camera in 1975. “When God created heaven and earth, he created all things. He also created barley, rye. If he didn’t think those things were good for man, he wouldn’t have let those things grow.” “Amen!” was Van Zandt’s reply.

God also created the poppy plant. “Clarksville was basically a place where we were all on heroin, all shooting up,” Van Zandt’s then-teenaged girlfriend Cindy told R.E. Hardy in the No Deeper Blue biography. Nau’s Pharmacy sold syringes, in addition to those great cheeseburgers.

“Tell you the truth, Townes was too bad of a drunk to be a good junkie,” said Phyllis Peoples, just 18 when she moved into a garage apartment ($40 a month) across the street from Uncle Seymour in 1969. Most of the heroin crowd were chippers.

Uncle Seymour had no idea this third rail shit was going on. The place to fix during backyard barbecues was at the threadbare trailer two blocks away, where Townes and Cindy stayed from Sept. ‘75 to mid ‘76.

When director James Szalapski came to Clarksville in Dec. ‘75 for an all-access look at Townes and friends for Heartworn Highways, decoys were devised to draw the nosy cameras away when it was time to find a vein.

Unk is immortalized as the old Black man in the cult documentary with tears streaming down his face as he listens to Townes sing his first composition, “Waitin’ Around to Die.” Washington would be dead by bladder cancer within a year, at age 80. “This old engine’s going to the roundhouse,” he told Dobson, one of many who visited him at the nursing home.

A benefit was held at Soap Creek to raise money to fix up Uncle Seymour’s house, which had running water only in the kitchen, so he could wait around to die at the domicile that defined him for over 40 years. As Greezy Wheels were setting up, an announcement was made: an angel had stepped forward to pay for the complete renovation. Money raised that night would go towards a fulltime nurse. But Seymour Washington passed away in the nursing home just 10 days later, Nov. 12, 1976. He’s buried in Evergreen Cemetery, section E, lot 75.

Watch 15 minutes of Townes and Uncle Seymour from Heartworn Highways.

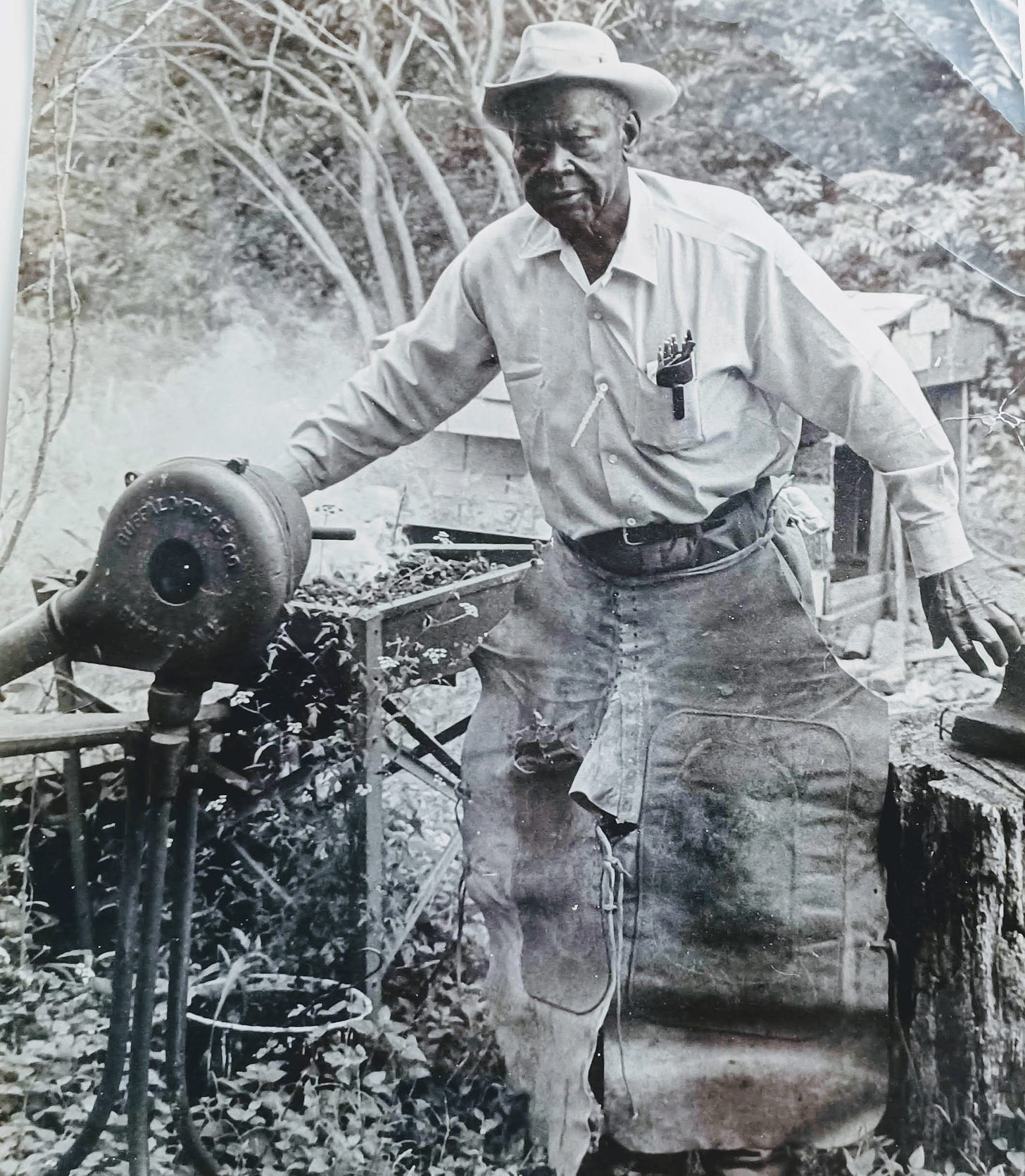

Described as a “soft-spoken, highly intelligent man” in a 1953 American-Statesman profile by Billy Lee Brammer, Washington (b. 1896) “towers over his backyard forge and anvil, clad in a muleskin apron.” By that time, Uncle Seymour had retired from his fulltime role as “the Walking Blacksmith,” of Travis and Hays Counties, but he kept horses of the well-heeled, well-shoed. A master of his craft, he handled equine footwear for the West Enfield Riding Club, as well as a woman from New York who trained show horses. In a short “Clarksville 1970” doc linked at the bottom, Washington talks about ginging horses for an advantage in the show ring. “You chew up some root ginger in your mouth and then you raise the horse’s tail and stick that hot ginger in his rear end,” said Washington. The anal burn makes the horse arch his back, impressing judges.

Washington apprenticed at Tab and Lee Bryant’s blacksmith shop on Lavaca as a 14-year-old in 1910. He also drove a buggy for the Pease family, reining horses named Mason and Dixon. Although former Texas governor Elisha Pease sided with the Union in the Civil War, he kept slaves, to whom he gave land in Clarksville after the war. Many continued to pick cotton for the Pease Plantation (Enfield is named after his birthplace in Connecticut) as free men.

When horses were replaced by cars, the demand for blacksmiths downtown disappeared and Washington got a job with the city department of sanitation from 1925-1942. Then he returned to his original trade, shoeing horses at ranches from Buda to Blanco, and also for the circus when Barnum and Bailey came to town.

He had the hardest time, he told Brammer, working with mules. “God made the horse and the donkey, but man made the mule. That’s why he’s so mean.” Brammer ends his article by declaring that Seymour Washington’s “heart is bigger than a mule. He’s a God-made man, you see.”

Uncle Seymour’s funeral packed Sweet Home Baptist Church with a mix of longhairs, Black neighbors and relatives, who Unk’s young friends had never seen before. “It took a long time for us white kids to be accepted in Clarksville,” said Phyllis Peoples. “I would say it was more of a lifestyle thing than skin color. They were hardworking people, and we were drinking and partying and playing music every day.”

Here’s an interesting 1970 documentary on Clarksville. Seymour Washington comes in at about the 10:50 mark.

A lot of plain old hippies lived there too. I once climbed a telephone pole to hook up cable for those houses...

Fine article Michael. My parents moved us to Austin in 1964 and our first small rental house was on W. 9th Street in Clarksville. My dad was a poor college student with two younglings. Around age three my first human memories are of the green, tree filled neighborhood of Clarksville hunting Easter Eggs in the little park by our house. Fascinating to know the original history of the neighborhood, I had no idea. By the time the 80s came I couldn't afford to rent a cottage there and it's filled with million dollar houses now- weird. To go back in time...