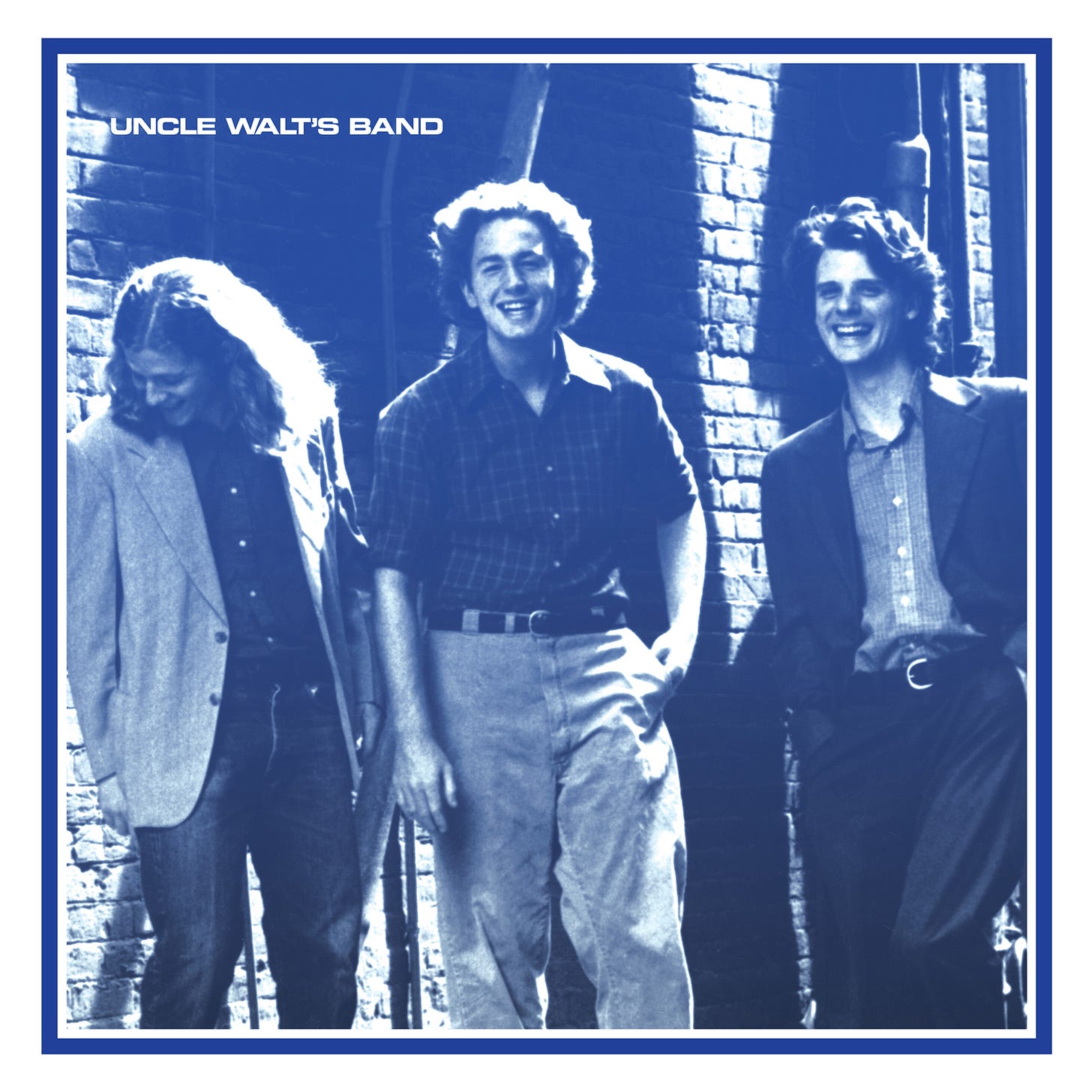

Uncle Walt's Band Came Knockin'

Austin was in love with "those boys from Carolina," but they somehow couldn't get a record deal

“Of all the musical groups which have moved here since the Austin music scene began to develop about six years ago, I don’t think any have intrigued, captivated, hypnotized or won the hearts of Austin fans like Uncle Walt’s Band.” - Townsend Miller of the Statesman, announcing the trio’s reunion, after a three-year hiatus, at Liberty Lunch in July 1978.

Mr. Miller hadn’t seen anything yet. The rebirth was sensational, as Uncle Walt’s Band- and their diehard fans- found a musical home at the original Waterloo Ice House at 906 Congress Avenue for the next five years. Not until Junior Brown played Sundays at the Continental Club circa 1989, had there been as strong a marriage of room and talent.

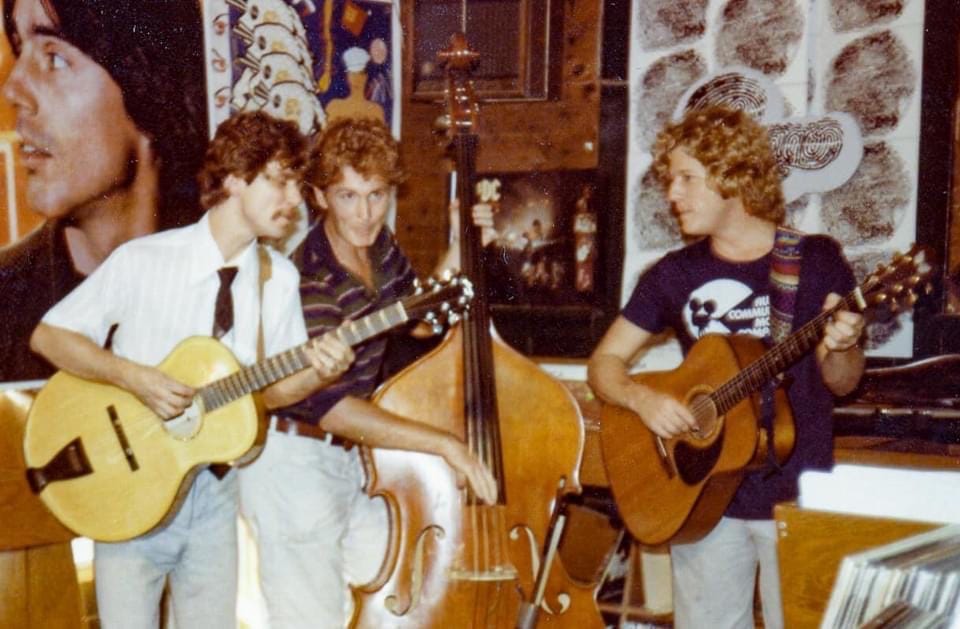

UWB played completely acoustic at first, but the crowd’s size and enthusiasm soon called for mics. “People went crazy over them,” Waterloo Ice House owner Stephen Clark said of guitarists Walter Hyatt and Champ Hood and bassist David Ball, who hailed from Spartanburg, S. C. “Someone called them ‘the Bluegrass Beatles,’ but they played a bit of everything.” Their trademark was harmonies so crisp and precise they could remove wrinkles.

The unsigned band taped an episode of Austin City Limits in 1980 and were championed the rest of the decade by Lyle Lovett, whose sophisticated country/jazz style came right from Hyatt. “Uncle Walt’s Band gave me my career,” said Marcia Ball, who’d been singing country covers as Freda with the Firedogs. “When they brought that first album to town, there was a cover song on it called ‘In the Night.’…I asked Champ what that was and he said ‘that’s Professor Longhair’ … and there I went.”

You can also hear the influence of David Ball’s “Don’t You Think I Feel It Too” on the songwriting of Lucinda Williams, another Waterloo Ice House regular. Clark opened the burger/beer joint in March 1976 with Roger Swanson, but didn’t have live music in the beginning. The first booking, Ain’t Misbehavin’, dictated that the Ice House would be a swing club, not a folk joint. Eaglebone Whistle, featuring future Lyle Lovett cellist John Hagen, was another regular act, as was David Ball, who’d recently moved back to Austin from Spartanburg to try to get a new band together.

Instead, the countertenor (dude sings like a lady) got the old band back together. Hyatt and Hood were living in Nashville, where their five-piece roots rock band the Contenders were building a cult audience and working with R.E.M. producer Don Dixon. But Walter and his first wife Mary Lou, who managed Waylon Jennings, were in the process of breaking up, so Austin was looking good. To sweeten the relocation, Clark gave the trio free rehearsal space upstairs from the club, so Ball had to move his standup bass just down the stairs for gigs. The band received 100% of the door which, at $3 cover, put as much as $200 in the pocket of each musician, twice a week. That was living large in Austin in 1978.

Uncle Walt’s Band had everything- the looks, the songs, the harmonies, the musicianship, the cool covers. It felt like history was being made on Congress Avenue. Soon, the trio would be a national act, so enjoy the up close and personal experience while you still can.

But stardom never came, and after five more years of playing clubs, UWB broke up again in 1983, with Ball, the best singer of the group, headed to mainstream country success in Nashville. Hyatt and Hood continued as a duo for a few weeks, but two-thirds of the trio drew less than half of the former crowd. Walter and his second wife, the former Heidi Narum, moved to Nashville in the mid-’80s to be near his daughter Haley. His acclaimed 1990 solo LP King Tears was produced by Lovett, but Hyatt was one-and-done on MCA.

Champ stayed in Austin, where his guitar and fiddle (self-taught as an adult) backed so many acts, most notably Toni Price for nine years of Tuesday “Hippie Hour” shows, and the Wednesday night sessions at Threadgill’s. His violinist son Warren Hood and guitarist nephew Marshall Hood keep the Uncle Walt repertoire alive every Wednesday at ABGB.

Tragedies felled Hyatt and Hood in their 40s, with Walter perishing in the 1996 ValuJet crash in the Florida Everglades, and Champ succumbing to cancer in Nov. 2001.

Their music, most of which they put out on their own, has been gloriously reissued by L.A.’s Omnivore Recordings from 2018- 2021. Listen to the first album, 1974’s Blame It On the Bossa Nova (self-titled by Omnivore) and there’s little doubt that Uncle Walt’s Band is one of Austin’s all-time greatest groups. The Lost Gonzo Band certainly thinks so, covering such Walt Band origs as “Getaway,” “High Hill” and “I’ll Come Knockin.’” (That’s like True Believers covering Zeitgeist.) “Those guys, with their sweet voices and harmonies and chord changes were so unique,” said Bob Livingston of the Gonzos. “They were a throwback to another age, and nobody could touch them.”

UWB first touched down in Austin in 1973, at the invitation of Willis Alan Ramsey, who saw them in Nashville at Our Place on March 5, ‘72. Ramsey’s sure of the date because it was his 21st birthday. He was also celebrating that day’s completion of recording the album that would make him the Harper Lee of redneck rock.

“I loved their creative original tunes, as well as their unique take on songs by Bob Wills, Ray Charles and Professor Longhair,” Ramsey recalled in the liner notes to Uncle Walt’s Band. “They made all cover songs their own.” Ramsey brought the trio to his Hound Sound studio in a shack on Baylor Street, but like the earlier sessions UWB recorded in Nashville with producer Buzz Cason, there was not much label interest.

But the trio was smitten with Austin, where they drew crowds to the original Saxon Pub on I-35 at 38th St., and to Castle Creek. Musicians were especially impressed. Gary P. Nunn gave Walter, Champ and David a place to stay at his “Public Domain Inc.” complex at 6214 N. Lamar, where one-room cabins rented for $50 a month.

“The boys from Carolina” (as Lovett immortalized UWB in “That’s Right, You’re Not From Texas”) especially loved how attentive the audiences were when they played, then erupted at the end of the song. “Uncle Walt's was not a bar band,” Ball said in a 2019 interview. “We were a listening band.” Not everyone in this guitar town got their fresh take on “folk swing,” however. “We had some people ask us, ‘Why do you all sing at the same time?’”

“We were adventurous,” Ball continued. “Like, Champ came in one day and said he liked that song ‘Hot Fun In the Summertime,’ so we’d work it out and play it that night. The audience would really get a kick out of it.”

The closest UWB, the Unpeggable White Band, got to a major label deal was when they were briefly courted by Warner Brothers in ‘75. The Walts were viewed as the next Dan Hicks and His Hot Licks, but when that well-promoted group failed to sell many records, WB eventually passed.

That heartbreaking process facilitated the trio’s first breakup. Hyatt and Hood went to Nashville, while Ball went back to Spartanburg and opened a bar. Three years went by. And nobody forgot them.

Austin music is inherently laid back, looking for the right feel and tone, but Uncle Walt’s Band was sharp, crisp and professional at all times. Their greatest influence on the music scene may have been in presentation. Their three-part harmonies were doowop-impeccable, plus there was a lot of craft in their swing. But what made them so appealing to Austin audiences simply confused the Nashville suits.

All praise to Omnivore for correcting the oversight, and bringing a lot of really terrific music back into the world.

One of the sweetest memories of my life is a long-ago summer night on the grass at Symphony Square, with UWB playing on the stage just across that little creek as thunderstorms lit up the sky all around us, but never rained on us. It was the purest, most healing kind of joy. <3

I remember well going down to the Waterloo on Congress Ave. and being spellbound with the whole experience: polite, attentive, enthusiastic audience who was also, treated to a very young Junior Brown playing the breaks.