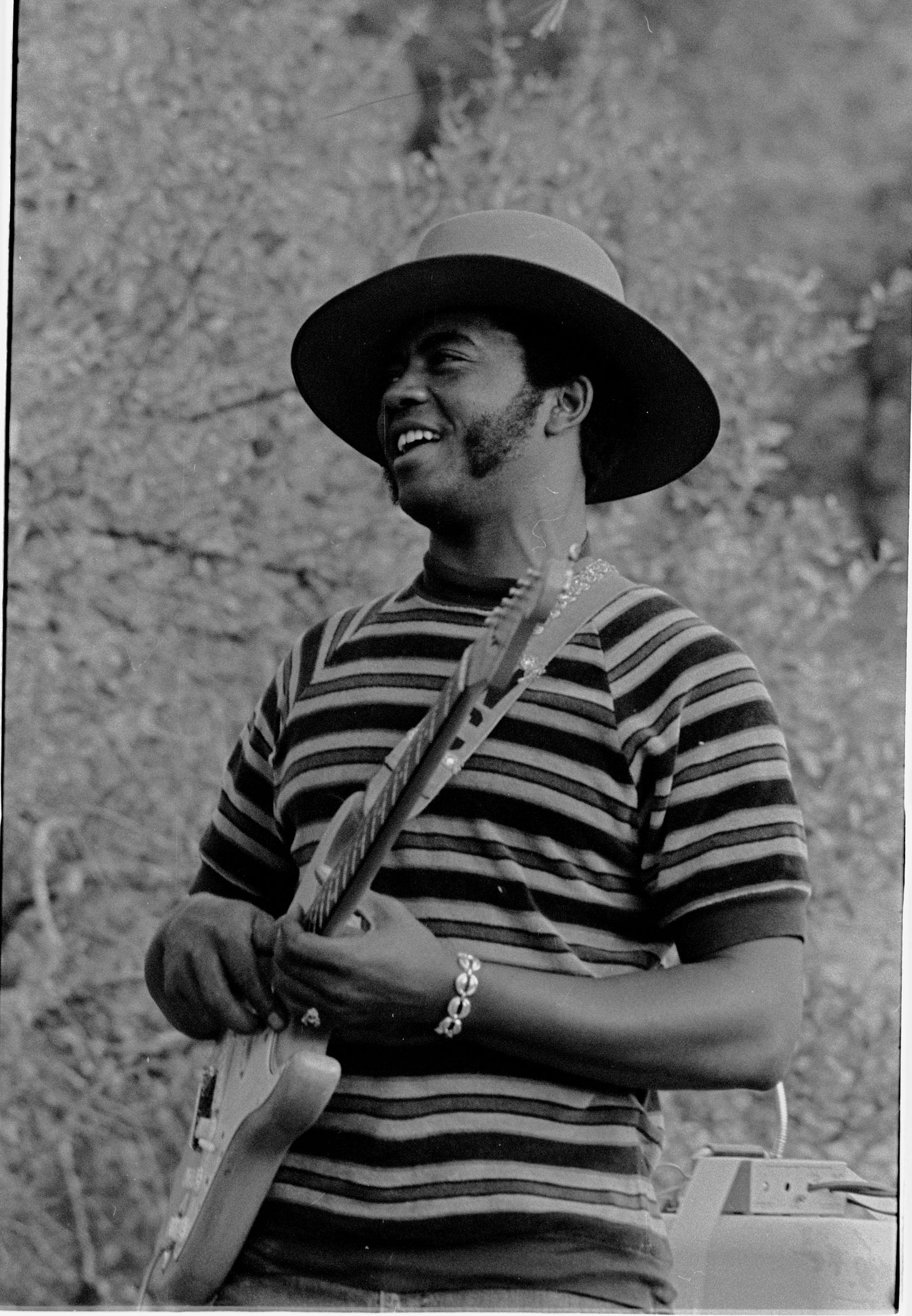

W.C. Clark, the gentleman godfather of Austin blues 1939-2024

Guitarist-singer mentored the Vaughan brothers and others in the real Eastside blues

We love our Austin musicians, but can they hold their own against national acts? That was a no-brainer when you considered W.C. Clark, who brought Memphis soul to stinging Texas blues guitar, and lent authenticity to young blues turks on the Austin scene of the early ‘70s. Although he was known as “the Godfather of Austin Blues” for the guidance he gave so willingly to blues obsessives looking for the source, he was often overlooked in the pantheon, and was woefully underrated. Some could sing as soulfully. A few could play better. But nobody did both better.

Wesley Curley Clark passed away this morning at 7 a.m. at Christopher House, just days after doctors found cancer, though his cause of death has not been determined. “It all happened so fast,” says manager Vicky Moerbe, who said Clark checked into Seton Hospital in Kyle after his Feb. 20 solo show at Giddy Ups. “He was acting erratically, not feeling like himself,” she says. After the tumors were found he was put in hospice care.

“We have lost one of the true masters,” says musician Carolyn Wonderland, whose band often opened for Clark’s. “W.C. was the bridge between at least three generations of Austin musicians… He was genuinely happy to share the joy and the spotlight with those around him.”

Clark had a special kinship with Stevie Ray Vaughan, who convinced his mentor to quit his job as an auto mechanic in 1975 to join Triple Threat Revue with Stevie and Lou Ann Barton as the other Threats. After about a year, W.C. left to form his own Blues Revue, and SRV’s band became Double Trouble. While in Triple Threat, Clark co-wrote “Cold Shot” with Mike Kindred, one of Vaughan’s biggest records. W.C. continued to get royalty checks through the years, and didn’t have to work as hard as he did in his 80s, but he was never too good for a gig. In the last years of his life, W.C. Clark played restaurants, dives, and even a gameroom in Hays County called Pinballz Kingdom. “He said playing kept him young,” says Anna Bosworth, the general manager at Giddy Ups, where Clark held a weekly residency for six years. “W.C. was always very engaging during his shows; answering the listeners' questions or telling wonderful stories about his life and songs that he wrote.” On his last show at Giddy Ups, Bosworth says he was “a little off, but I think his regular followers, myself included, just chalked it up to being old or being tired and not feeling well.”

“He didn’t just want to sit home by himself,” says Moerbe, who’s been his manager since 1987, when a 48-year-old Clark self-released his first album. Always the teacher, it was important for him to let fans know where the blues really started in Austin, in such Black clubs as the Victory Grill, Charlie’s Playhouse, the Hideaway, Sam’s Showcase and Ernie’s Chicken Shack. W.C. played ‘em all.

Clark grew up in a big, religious family in the St. John’s Colony neighborhood of North Austin, near where the ACC Highland campus is today. As a 12-year-old he played guitar for the Southern Wonders gospel quartet, but his first paying gig was as a 16-year-old at the Victory Grill, joining T.D. Bell’s band the Cadillacs. A stint with Blues Boy Hubbard and the Jets at Charlie’s Playhouse led to his discovery by Joe Tex, the “Chitlin Circuit” showman from Navasota, who took him on the road until his early ‘70s retirement to become a Muslim minister. Clark was also proficient on bass, which made him in-demand as a sideman.

When Clark returned to Austin in the early ‘70s, the blues scene had changed significantly, with the action moving west of I-35 to the One Knite, and the New Orleans Club. “Storm (with Jimmie Vaughan and Doyle Bramhall) was the first all-white blues band I’d ever seen,” he told me in 2002. W.C. played bass in James Polk and the Brothers, then started his own interracial band when he recruited Polk’s singer Angela Strehli for a new outfit called Southern Feeling. Eventually the singer and guitarist became a couple.

Clark didn’t sign his first record deal, with Blacktop in ‘94, until he was 55. By then he’d already had an Austin City Limits taping on his 50th birthday, shared with SRV, who lobbied hard for Clark. Finally with national distribution, Clark made up for lost time at Blacktop, winning two W.C. Handy Awards, the most prestigious in the blues field, in the “blues/soul” category. His most-telling Handy was in 1998, when he was named Artist Most Deserving of Wider Recognition. That could be engraved on his tombstone, for W.C. Clark should’ve been one of the biggest names in contemporary blues. Maybe his style was more soul than blues, and he was stuck in the middle.

Clark’s biggest record was his first for the Alligator label- 2002’s From Austin with Soul. "I've never made a record before that felt so right," Clark said by phone from a Travelodge outside Milwaukee. Garnering rave reviews and scattered airplay on stations as far away as Ottawa, the man in the fedora took to the road like a 23-year-old with a debut album to push. "Man, it's like everything is falling into place after all these years." Another Handy for Song of the Year came for “Let It Rain” from that album.

Five years earlier, Clark wasn't sure he'd ever play music again. Consumed with guilt after a van he was driving flipped off the road 40 miles north of Dallas, killing his fiancee Brenda Jasek and longtime drummer Pete Alcoser Jr., Clark didn't think he could ever take the stage again with the same fire. His album Texas Soul was winning new fans, but all he could think about was what he'd lost.

But after a few months in mental limbo, he had a revelation. "I was sitting on a commode, of all places, and I decided to stop feeling sorry for myself," Clark said. "I stared at my hands, which had been hurt in the accident, and I realized that it's all in God's hands and what he put me here to do was sing and play guitar, so what was I waiting for?"

1998's Lover's Plea, which included a song written for Jasek called "Are You Here, Are You There," won another W.C. Handy, and when Austin City Limits repackaged a jam between Clark and Vaughan on a "Best of" show later that year, he was exposed to a new generation of blues guitar aficionados. Getting back in the van was the hard part, Clark said, but finding appreciative crowds at every stop kept him going.

"Folks are always writing about how I taught Stevie and Jimmie, but I actually learned as much from them as they learned from me," he said of the Vaughan brothers. "The No. 1 thing those young cats taught me was endurance. As long as the people are coming out to see you, you play as long and as hard as you can every night."

The blues are about making something positive from a negative situation -- a good song from a bad time -- and nobody knew about such silver linings like Clark. After the fatal '97 accident, doctors ran several tests on W.C. to make sure there weren't internal injuries. And that's when they detected that he had prostate cancer.

"They never would've found it if it wasn't for that accident," Clark said. "How's that for dumb luck?" After doctors implanted time release pellets in Clark's prostate, the cancer had almost completely disappeared by 2002.

"I done survived a lot in the last few years," said Clark. "It wouldn't make sense to let up now."

Eventually life catches up to you, and taps you on the shoulder to say it’s over. A working musician for almost 70 years, Clark “played music up to the last week of his life,” says manager Moerbe. “He was surrounded by people who loved and supported him until the very end. What’s a better legacy than that?”

A funeral is being planned. Clark is survived by a daughter, Brittany Mays, two brothers- Daniel and Charles- and sister Mary.

Excellent piece, Michael. I'm glad you mentioned WC's bass playing side. First time I saw WC play was with Triple Threat Revue. Stevie was only singing on a couple of songs at that time and, to be honest, I didn't think he would progress beyond that many. Lou Ann was so sexy and such a powerful singer and presence, whenever I saw her sing I had goose bumps that lasted a week or two afterward. I can't remember what kind of bass WC was playing. I don't know why that detail bothers me, but it's bugged me for years. I know it wasn't a long scale Fender.

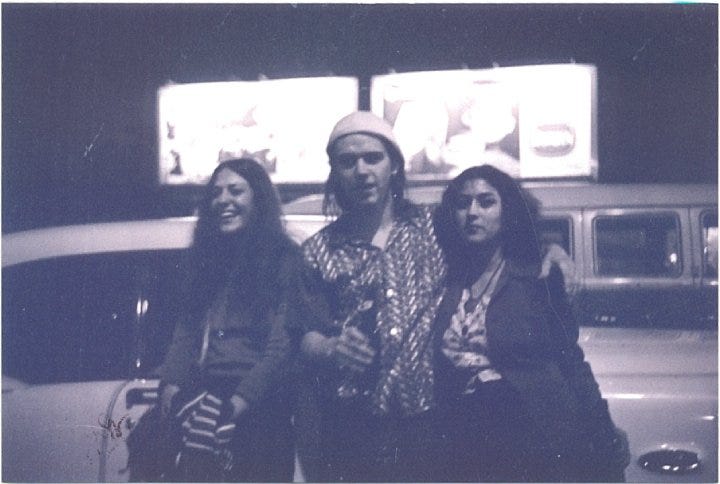

ACL photographer Scott Newton and I would rarely miss a WC gig in the late 80s. We really wanted more folks to come out to see him, so we hatched an idea to get him on an Austin City Limits taping by pitching it as "best of" the musicians whom WC had played with, calling it a tribute to WC on his 50th birthday. ACL really wanted to do another SRV taping, but Stevie's manager Alex Hodges was uninterested. WC called Stevie and Jimmie himself and asked if they’d play our proposed ACL taping, and they both said Yes. I picked the drummer and bass player (Barry "Frosty" Smith and Jon Blondell). Then we pitched it to ACL producer Terry Lickona, and he said OK. Helping make that event happen was one proud day for me and for Scott, but most importantly, for WC, a wonderful person who deserved more respect and love. His voice, the tone of his guitar, his smile, his willingness to help other people, he was a heavy soul. At that time it was rare that you were featured on ACL if you didn’t have a national release. He got one soon after that taping. The song featured in the clip you posted was written by Stevie and WC at rehearsal.