"Willie Nelson Can't Sing"

Dumbest sentence I ever wrote was as new country music critic in Dallas

When I first started reading music reviews in newspapers and magazines, I thought the opinions were fact. Then one day a critic trashed Physical Graffiti and I realized the scribe tribe could be absolutely clueless. Years late I’d have first person proof.

When it was my job for over 20 years, I felt that daily newspaper music critics were meaningless and, at their worst, pretentious. Like anybody really cares what we think about people much more talented. The goal was not to get readers to share my opinion, but to have them read the whole thing. I wanted attention for the writing, not the assessment. I was on a mission of elegant ignorance. I didn’t care about the blowback, that was part of the act.

Please direct your attention to Exhibit A, the lead story of the features section from the Dallas Morning News in March 1992. Based on a few clippings of edge-of-Nashville acts Rosanne Cash, Foster & Lloyd, Kentucky Headhunters and the O’Kanes, I had just been hired as country music critic in the genre’s No. 1 mainstream market in the U.S. For my first essay on a Texas country music legend, I opened by writing that Willie Nelson can’t sing. WHAT??!!

I meant in the traditional way of country singers, but that wasn’t instantly apparent in this meandering piece. I was being provocative, but every time country radio ragged on me, they’d take calls from folks who’d say, ‘Isn’t he the (bleep) who thinks Willie can’t sing?!” After two years of being “the country music critic who hates country,” and before construction was completed on the rail to ride my ass outta town, the DMN moved me over to pop music critic. The era of “the Red-Headed Strangler” was over! After this video that proves Willie is among the greatest country singers of all time, I reprint the DMN article which advanced Farm Aid V at Texas Stadium.

by Michael Corcoran

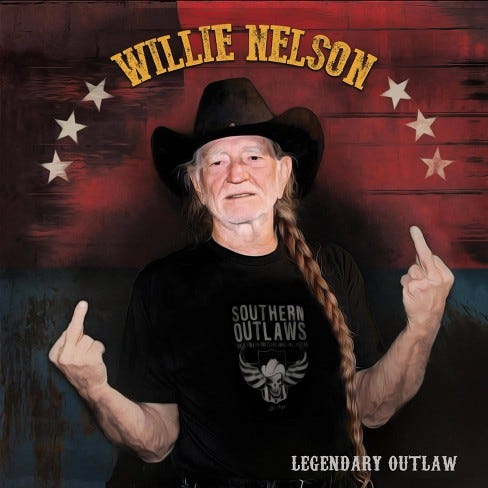

Willie Nelson can't sing. Call him a song stylist if you must, but that doesn't make his voice any less nasal or behind the beat. In a genre that rewards masculinity with gold and platinum, Nelson is brave enough to sing like a wounded she-devil. Wearing pigtails, no less.

His vocals skitter and shine like a flashlight into the emotional caverns of his songs. Willie Nelson can't sing the way Larry Bird can't jump.

When Nelson closes his eyes during ''Night Life'' and shakes his chin at ''listen to the blues they're playing . . . listen to what the blues are saying,'' the words mean more than when Ray Price sang them. Then ''Shotgun Willie'' flails away on his beat-up guitar like an escaped convict filing his shackles. Listen to what the blues are saying.

No, Willie Nelson can't sing in the classic way, but it's the way he can't that has helped make him an American folk hero. That and the ability to fatten thin air with miraculous songs and an unflinching image of down-homeliness. He's made the world richer by creating ''Crazy'' for Patsy Cline, ''Hello Walls'' for Faron Young, ''Funny How Time Slips Away'' for Billy Walker.

If Nelson could sing, he probably wouldn't have written so many great songs. He wouldn't have reinvented himself 20 years ago into a country music outlaw. He wouldn't constantly organize his friends and famous acquaintances to perform in cultural extravaganzas he originally called ''picnics'' and now titles Farm Aid. If he could sing, he wouldn't be Willie.

And even while stepping up his performing schedule to help chip away at a massive IOU to the IRS, Nelson leads Farm Aid to its fifth benefit concert Saturday at Texas Stadium near Dallas.

''The main goal is to educate the public about the hard times facing the American farmer and the effect that has on all of us,'' Nelson says. Recently, attention has been focused as much on the plight of Willie Nelson as that of the small, independent farmer. To wit: In 1990, Nelson was served with a $32 million bill for delinquent taxes - one of the largest ever for an individual. The amount was later modified to $16.7 million. To put a dent in the debt, Nelson released Who'll Buy My Memories? in conjunction with the IRS. He hoped that the CD, which was marketed on TV, would sell 3 million copies, as many as his best-selling LP, 1978's Stardust. His collection of acoustic songs sold just over 200,000 copies.

Even worse, he’s reeling and dealing with the death of his son Billy, who committed suicide on Christmas 1991.

Willie Nelson doesn't write songs like he used to.''It was a lot easier to write when I was young and hungry, with something to prove,'' he says. ''Nowadays I have to rely on pure, raw ego to get me motivated. The challenge is now in other things.''

Other things like Farm Aid. Nelson gets out and lets the public know that bacon and eggs don't grow on trees and, if they did, who planted the trees? He tells politicians that the guy who printed the label on a loaf of bread makes more than the man who grew the wheat that made the bread, and that's not right. Then he calls up more famous friends and goes to Vegas until it's time for the big day.

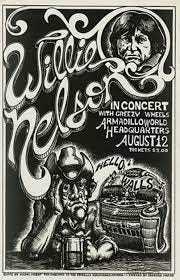

The seeds for Farm Aid V were planted in 1972, when Nelson moved to Austin, Texas, after his house in Nashville burned down. Even before he had a chance to settle in, Nelson found signs that country music was about to change.

At the Dripping Springs Reunion, an underattended music festival, he saw firsthand that some rock 'n' roll fans loved country music, and some country fans liked rock 'n' roll. He also learned that massive events have a much greater chance of failure when you have to pay the acts. One of the promoters later killed himself, and the other had to clean out his personal bank account to pay Loretta Lynn her $30,000 guarantee.

To Nelson, the concert was a revelation, however. In Texas, where the '60s lasted until 1974, you didn't see Bubbas and Jolenes congregated in the same place as Ciscos and Sunshines.

Nelson started growing his hair and wearing an earring. He stopped shaving.

''I saw that the kids were smarter than I was,'' he says. ''Here were all these bands knocking out the world in T-shirts and jeans, and I'm wearing these uncomfortable suits. I thought, 'Well, maybe I'm dancing to the wrong drummer.' ''

He put in a call to his good friend Waylon Jennings and said, ''Man, you're not going to believe what's going on down in Austin.'' When Jennings first played the Armadillo, opening for Commander Cody, he took a look out at the place packed with hippies and almost didn't want to go on. Pre-outlaw Jennings was used to people two-stepping to his music, not boogieing as if they had checked their rhythm at the door. ''They're gonna love you,'' Nelson assured him. The crowd went wild when Jennings started his set and later called him back for three encores.

Nelson held his first Fourth of July Picnic in 1973 on Burt Hurlbut's ranch in Dripping Springs, Texas. Just as with the lineup of Farm Aid, Nelson's picnics were mostly country, but there were a few rock bands and folkies as well. Doug Sahm compares the picnics to the '60s musical festivals in San Francisco, but with much less face-painting and a lot more cowboys.

Sahm, who has known Nelson for almost 30 years, tries to explain the Nelson charm that draws people in: ''Man, it's like . . . ya know, it's this sorta . . . I guess the only way to say it is that Willie's just so dang nice. I've never seen him yell at anybody or even walk away mad. He's the coolest.''

Sahm offers a story to show how hard it is to fluster Nelson.

''One time a bunch of us were sitting around a campfire, and Willie got too close, so his pants caught on fire. He didn't even notice until the fire was almost up to his knee. He looked down, saw the flames and said, 'What have we here?' Then he threw a few handfuls of dirt on his pants until the fire was out.''

''Saintly'' is how Wilson describes Nelson's demeanor.

''He possesses a patience with his fans which I've only seen rivaled by Muhammad Ali. He'll sign autographs for hours and chat with fans until he's either talked to every one of them or one of his boys leads him away,'' he says. ''There's no questioning the size of Willie's heart. I mean, who else with all his financial problems would put on a benefit for someone else?''

Only a moron would have read the whole article and come away thinking you had anything but admiration for Willie, and his voice and his whole body of work. You were right by the way, he doesn't sing like any other country crooner!

One of my greatest regrets is never going to one of his picnics when I lived in Texas. I enjoyed your article.