Austin On the Map: Junior Brown

Before Charley Crockett, there was this guit-steel master who charmed the world

This is a chapter from the upcoming Austin On the Map: The Musicians Who Made the Live Music Capital Cool.

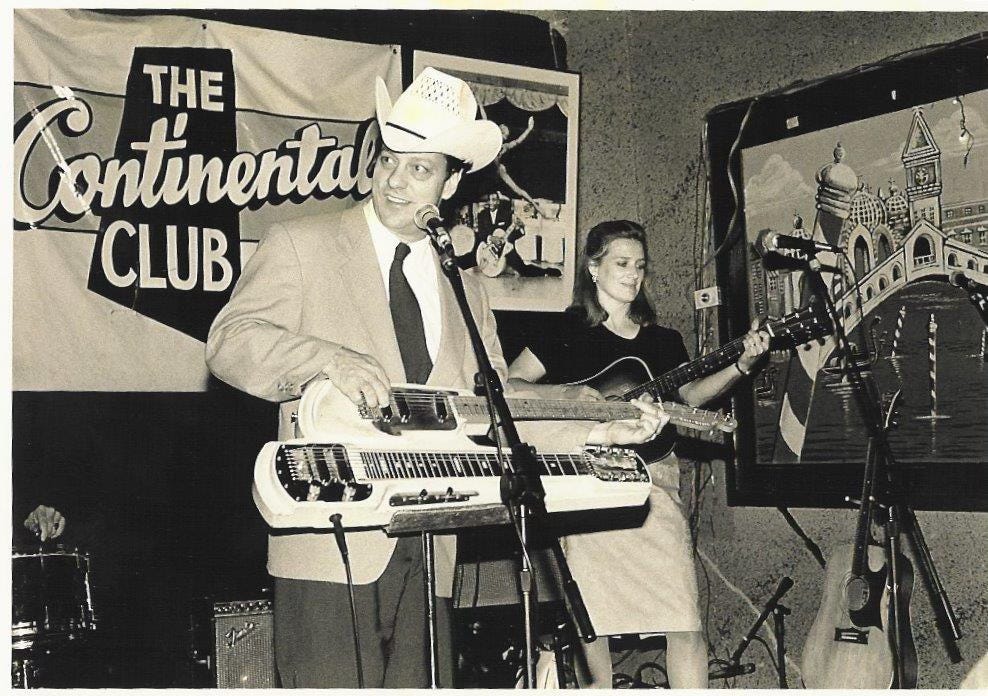

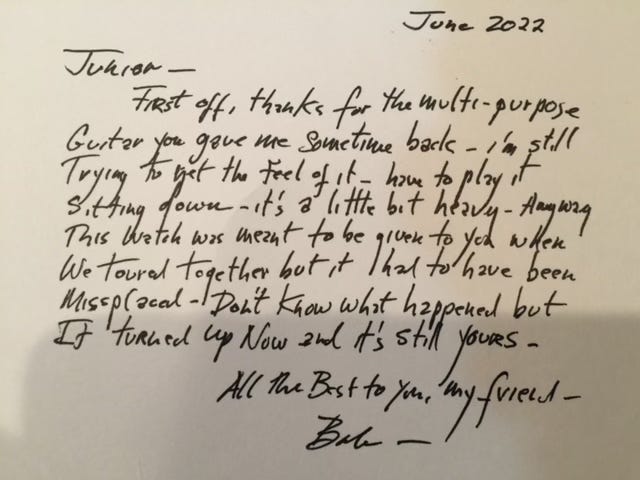

Junior Brown and his double-neck “guit-steel” didn’t become a thing until the early ‘90s, when he and rhythm guitarist wife Miss Tanya Rae went from packing Henry’s every Tuesday to becoming a national fascination with his scintillating live sets and quirky videos on CMT. But the honky tonk time machine had been playing music in Austin clubs for almost 20 years before his big breakout. Coaxing sparks out of his guitar contraption, with a voice deeper than the holler, Junior Brown was Jerry Reed and Ernest Tubb in the same suit. Everybody loved him, even Bob Dylan, who gave Junior an engraved pocket watch after he opened some shows.

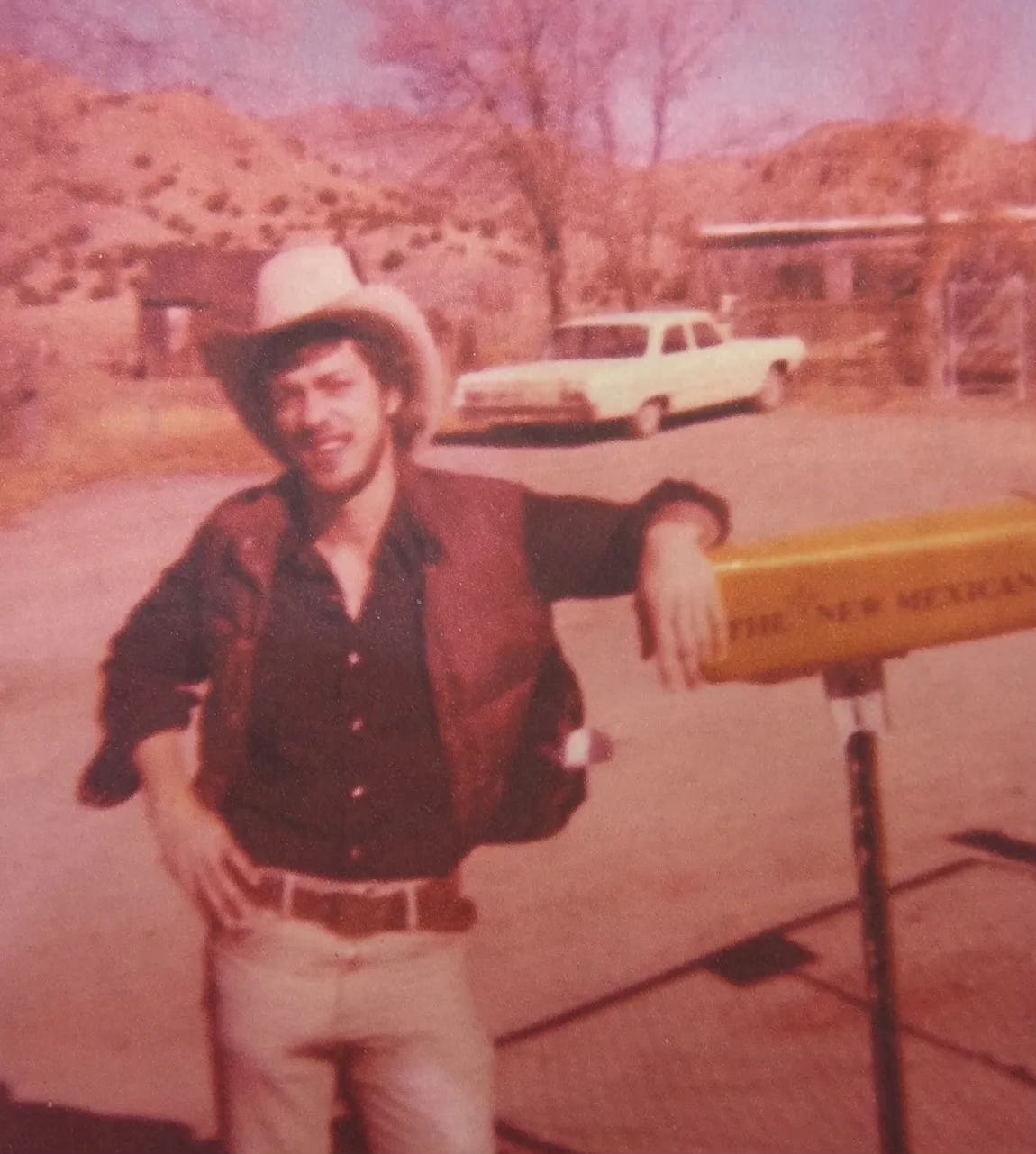

Junior Brown made Austin cooler than Nashville, just like it was in ‘74, when he came to town from New Mexico with bluegrassy country band the Last Mile Ramblers. Statesman country columnist Townsend Miller called the Ramblers “one of the finest bands ever to visit Austin,” after catching their second set in town at the River City Inn (304 E. Sixth). “Townsend adopted us,” said Junior, “even putting us up at his house.” Miller and wife Rita were empty-nesters who said “stay as long as you want,” which ended up being about a month.

The group was also embraced by Kenneth Threadgill, who Junior said was a lot like Townsend in that, “they were older guys that had the minds of younger people. They were out in the clubs every night because they just loved the music.”

Before they moved back to New Mexico, the Ramblers had a regular gig at the Texas Opry House annex, a cozy club that eventually became part of Arlyn Recording Studio after Willie Nelson bought the building in ‘77 and renamed it Austin Opry House. “When I was recording Guit With It (at Arlyn in 1993), I noticed the old fireplace that had been partially plastered over,” Junior said. “My mind immediately went back to when Austin was such a different place, and there were pickers and singers inhabiting that little room every night.” Willie sat in almost nightly at the club that’s been almost forgotten. Other regulars included Milton Carroll, Dee Moeller, members of Plum Nelly and Flaco Jimenez. “Musicians from all over were flocking to Austin to see what the fuss was about.”

Junior later played with Dusty Drapes and the Dusters, then Tex Thomas and the Danglin’ Wranglers on Sunday nights at Hut’s, which led to a short stint with Asleep at the Wheel. J.B. was a head-turning hired hand who cobbled gigs to pay the bills, but his schedule became more regular when he joined Alvin Crow and the Pleasant Valley Boys on guitar and steel in 1980. Besides the hippie joints like Soap Creek #2 (the old Skyline Club), the hard-gigging Crow band played the Broken Spoke for hardcore country fans every week. One night in ‘82, “cowpunk” pioneers Rank and File saw Junior at the Spoke and stole him away to replace Alejandro Escovedo on a European tour opening for Elvis Costello. It wasn’t Junior’s style of country, and he didn’t like the punks bumping into his steel guitar stand, but Rank got him out of Austin for a few months.

He didn’t become Junior Brown, solo artist, until a 1984 single of “Too Many Nights in a Roadhouse” on Speedy Sparks’ Dynamic Records announced the arrival of the brilliant triple-threat (singer-songwriter-guitarist).

Marveling at a double-neck guitar Michael Stevens had made for Christopher Cross, Junior designed the guit-steel hybrid in the early ‘80s so he could more easily jump between guitar and lap steel. Stevens finished the stringed Frankenstein in 1985.

The next year Brown moved to Claremore, OK to teach guitar at the Hank Thompson School of Music at Rogers State College. His parents had both been educators- father Samuel E. a professor at St. John’s College in Santa Fe, and mother Dorothy a noted cellist- who were not too pleased when Junior dropped out of high school in Santa Fe to play the bars. “I started out in the rock clubs,” said Brown, once backing Bo Diddley, “but there was more money playing the country bars” like the Play Pen and the Turf Club.

Junior also took classes at Rogers on a Pell Grant, mainly for the free room and board. Two of his instructors were Texas Playboy legends Leon McAuliffe, the steel guitar pioneer, and guitarist Eldon Shamblin, but Junior didn’t learn much in the classroom, where “they mainly just told Bob Wills stories,” he laughed. After class was the real education, with Junior playing in their band. The first recording of Junior’s “Hillbilly Hula Girl” had him trading licks with Leon on a demo cassette.

It was during his time at Rogers that Junior met Tanya Rae Rasberry, one of his guitar students, who he’d marry in 1988. Her steady rhythms on guitar and baritone-sweetening harmonies would be key to Junior’s rise, plus “the lovely Miss Tanya Rae” added to the visual sense. Born again Christians, the Browns dressed like a couple going to church in Waco, which was refreshing during that time of upstart country bands in embroidered gabardine jackets. Junior notoriously had no use for dress-up country bands like BR5-49, that he was often co-billed with. He was not a nostalgia act!

Marty Stuart, during his mainstream fling of the ‘90s, was another one who brought out Junior’s grumpiness. One night, Stuart and his running buddy Travis Tritt stopped in to see Junior at Headliner’s East on Sixth Street. They were partying after filming the video for “Put Some Drive In Your Country” at the Black Cat Lounge, causing a bit of a ruckus in the back of the club. After the set, Stuart told Junior he had recently purchased Ernest Tubb’s old tour bus and it was parked outside. “You wanna come see it?” But Junior passed. “The last time I was in that bus,” he said after Stuart slipped away with Tritt, “so was Ernest Tubb.”

Brown’s natural disdain for Nashville was stoked by an ill-fated 1988 relocation with his new bride. He unveiled the guit-steel backing Peter Rowan at the Grand Ol’ Opry, but gigs were rare. “We were hocking everything we owned,” said Junior. “One day we sold a piece of jewelry for $150 and I said we could either get our phone turned back on or put gas in the car to drive to Austin,” Junior recalled. “I’ll start packing,” was Tanya Rae’s answer.

It was a great decision. The very first night back in town, Junior got a job with Al Dressen, whose Sausage Swingers (after Dressen’s family business), had just been renamed the Super Swing Revue. But it was the solo-billed shows with Tanya Rae that built his following. Their Sunday night residency at the Continental Club in ‘89 started slow, with owner Steve Wertheimer having to dip into the till to keep the reluctant Browns coming back. But after word got out that there was a guy in a cowboy hat who interjected Jimi Hendrix and surf guitar into his offbeat country songs, the club was packed. “I’d look out into the audience and it was full of guitar players,” Junior said.

The Browns added Brother Steve Layne on standup bass and went through drummers at a pace that suggested a documentary on those days be called Spinal Hat. Most notable in this game of musical drum seats was Buddy Miles, who brought an air of legitimacy to the Jimi licks. “He could play anything,” Junior recalled. “He had so much resonance, even with the brushes.” Brown also played with the Experience rhythm section of Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell at a festival in Seattle.

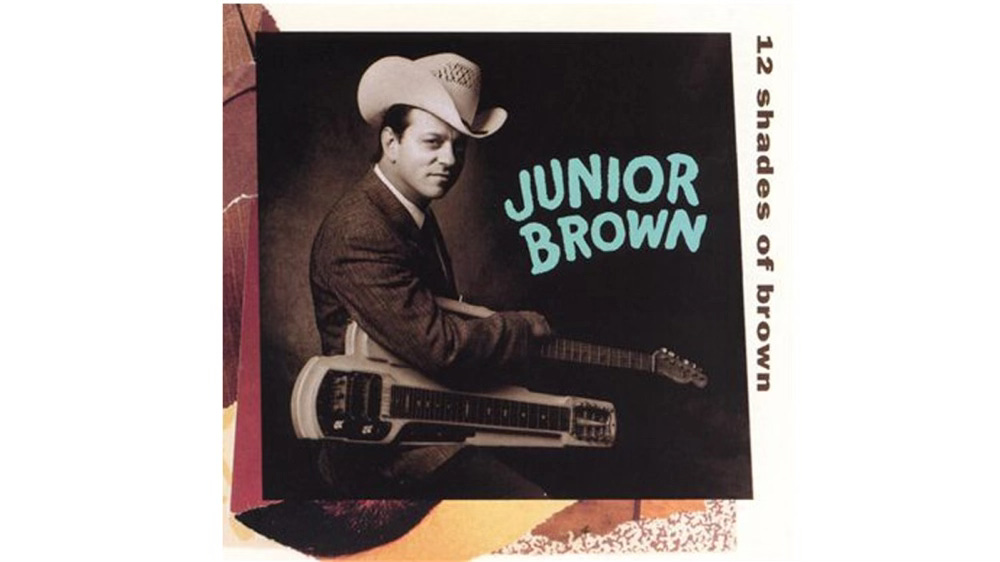

Junior points to a Thursday set at SXSW 1989 as the turning point in his career. In the Continental audience was Nashville booking agent Bobby Cudd (who still books Junior). At that same SXSW, a cab driver was playing a cassette of 12 Shades of Brown when his fare Nick Lowe asked “who’s that,” which led to its release on Jake Riviera’s Demon Records in 1990. Cudd dubbed his copy of the cassette and shopped it around Nashville before Curb, the home of Tim McGraw, showed interest.

Recorded at Spencer Starnes’ Bee Creek Studio, and produced by Brown, 12 Shades, which kicks off with “My Baby Don’t Dance to Nothin’ But Ernest Tubb,” was recently listed by Rolling Stone magazine among “The 50 Country Albums Every Rock Fan Should Own.” The LP was funded by Lockhart club owner Dwayne Kaufman, who booked the Browns into his Sea Willow Bar & Grill and was blown away. “He didn’t ask for anything,” said Junior, “not even that I pay him back.” Kaufman was eventually reimbursed $5,000 when Curb reissued 12 Shades in 1993, along with the new Guit With It.

Brown insisted on producing his albums, which was fine with Curb. “They thought, ‘well, we can’t change this guy, so we’ll just support him,” said Brown, which is what every artist wants to hear. But Curb dropped the ball in other ways. They misspelled Junior’s instrument “guilt-steel” and one of his signature tunes “My Wife Thinks Your Dead” on Greatest Hits, for instance, and sent producers of Me Myself & Irene an inferior take of “Highway Patrol” for the opening sequence. Junior had re-recorded it with Pig Robbins on piano. But what especially infuriated Junior was when he recut “Freedom Machine” with legendary engineer Eddie Kramer, and the Long Walk Back LP used the lackluster original version. “That was three days in the studio wasted.”

Junior’s two-step with Nashville garnered three Grammy nominations, and a CMA award for Best Country Music Video in 1996 for “My Wife Thinks You’re Dead.” He also rated a nine-minute segment on CBS News Sunday Morning. His cult became a fanbase.

Junior’s fire and technique on an instrument of his own design has made fans out of legends like steel guitar giant Lloyd Green, who credited Junior with coaxing him out of retirement. They like what he’s doing and seek him out.

“One day I got a call from Duane Eddy,” recalled Junior. “He said ‘Hank Garland loves your playing and wants to meet you.’ Well, that knocked me out! Hank Garland was one of the greatest guitar players of all time. This man invented reverb for amplifiers!”

Garland, whose career was cut short by a 1961 car accident that left him with a brain injury, lived in Florida until his 2004 passing, and Junior would stop by whenever he came through on tour to pay his respects. On one visit Garland presented his protege with a Leo Fender lap steel guitar, which may have been a prototype because it didn’t have a serial number. It’s made out “To my best friend Junior Brown,” and signed Hank Garland.

Junior never did win a Grammy. Do you think he cares?

PREVIOUSLY

One of my favorite bands. I have great memories of a not too crowded set at the Continental Club .Just closed my eyes and listened .

Great edu-ma-cation on one of my favorite acts. Only seen him in person twice, but it was awesome!