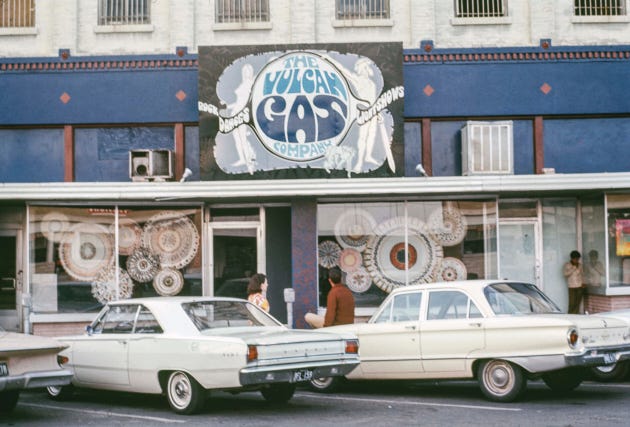

Austin's first hippie mecca: Vulcan Gas Company

The '60s: Storefront on Congress Avenue opened for the Armadillo

There were folkie clubs like the Cliché in West Campus, the Eleventh Door on Red River and the Chequered Flag on Lavaca, which handed out a 45 containing the very first recorded version of Jerry Jeff Walker’s “Mister Bojangles” during the 1967 grand opening week. Before that, Bill Simonson’s chairless id club on 24th St. across from the Varsity Theater was Beatnik Central, where “darkness was the decor” (Jerry Jeff Walker) and everybody sat on the floor and snapped their fingers. The groovy Methodist Student Center at 2423 Guadalupe St. had a coffee shop with candles. And, of course, there were the Thursday night “folk sings” at the Texas Union. But things were about to change for the louder.

When Bob Dylan and the Band played their first-ever concert together at Municipal Auditorium (later “Palmer”) in September 1965, the first set was solo acoustic and the second set was one of raging electric guitars and pounding rhythms. And that’s how Austin music segued in the ‘60s, when folk music gave way to rock n’ roll.

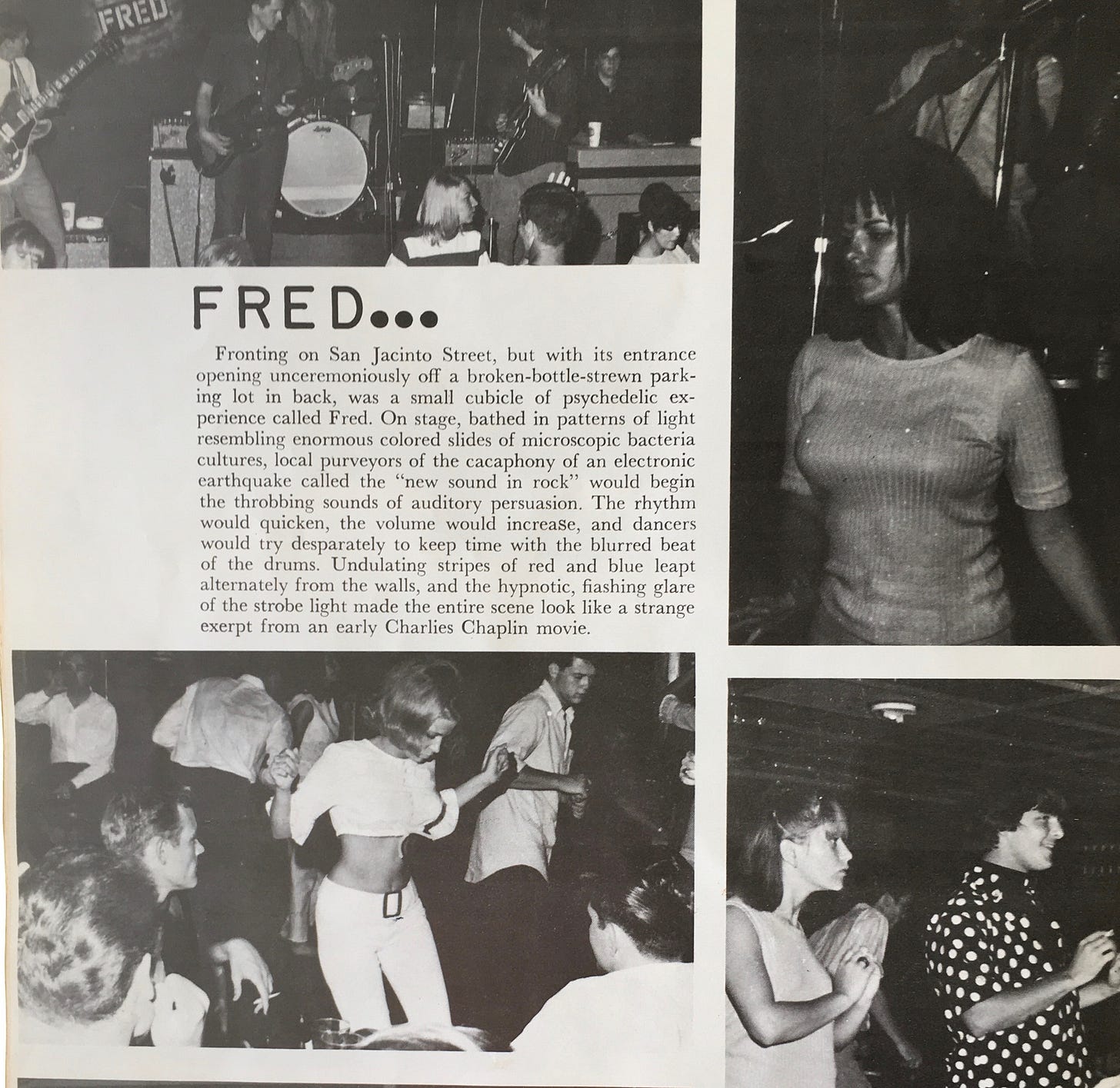

The San Jacinto strip between 15th and 19th was where the action was for rock bands and fans in the mid-’60s. Fred was Austin’s first “hippie club” at 1809 SJ, but lasted only a few months before it was shut down in late ‘66 for serving alcohol to a minor. In it’s place came Marie Nohra’s Club Saracen, which also featured light shows with bands like Conqueroo, Sweetarts and the Chevelles, but moved from Saint Jack to 1418 Lavaca in 1968, replaced by the Red Baron and then Hungry Horse. Marge Funk’s Jade Room booked garage rock like Roky Erickson’s first band the Spades on week nights, but the weekends catered to the college crowd with cover bands like the Rhythm Kings, moonlighting music teachers from Black high schools who played soul music and jazz/swing.

On Red River you had the New Orleans Club, which based its name on the preferred Dixieland jazz, but then started booking rock acts like the Wig, and the 13th Floor Elevators, whose sets often aired live on KAZZ-FM.

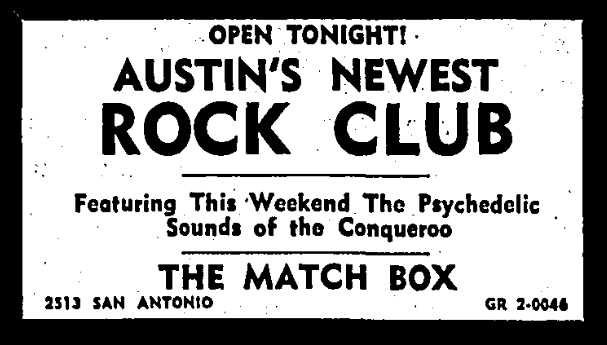

West Campus got a rock club in Dec. 1966 with the Match Box at 2513 San Antonio St. Conqueroo, Mance Lipscomb, the Nomads and others rotated on the schedule with experimental films. By the end of ‘67, it was the Match Box Theater, where you could watch movies and drink beer four decades before Alamo Drafthouse.

After the Nov. 1966 release of the mind-expanding debut LP Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators, with the hit single “You’re Gonna Miss Me,” the Elevators outgrew the clubs and pressed the need for a bigger venue. The Electric Grandmother collective rented Doris Miller Auditorium on the Eastside in Jan. ‘67 and booked The Elevators and Conqueroo, drawing 2,000 fans, but the acoustics were horrendous.

The Eastside welcomed longhairs, with the I.L. Club and the Ascot Room on E. 11th occasionally booking hippie bands, who drew better than the Black blues acts. Conqueroo, which had an African-American in Ed Guinn, led the Eastern migration, though the I.L. sign called them “The Kangaroos.”

The Electric Grandmother became the Vulcan Gas Company and put on the “Love-In at Zilker” in September 1967. The next month, partners Gary Scanlon, Don Hyde, Sandy Lockett and Houston White rented a big, ugly storefront at 316 Congress from Joe Dacy. Neighboring businesses didn’t want the hippies, but Dacy showed up unannounced one night and was impressed with what was going on. Pay the rent on time and we’re cool.

Others weren’t so understanding. With a former resident in the White House, sending boys off to Vietnam, there was a tense situation between war-protesting longhairs and law enforcement in Austin (even though it was an ex-Marine with a crewcut who killed all those people from the Tower in 1966). A beer and wine license would only draw more scrutiny, so the Vulcan didn’t even try to get one. The Statesman, whose city columnist Wray Weddell had a particular distaste for the hippie hangout, refused ads from the Vulcan the first year, according to Hyde. Which made the club’s 23” x 28” posters of great importance, as such artists as Gilbert Shelton, Jack Jackson and Jim Franklin blew minds and sold tickets.

Rent was $350 a month, but since the only income was the admission fee, usually $2, money was always an issue. There were often more people loitering in front and behind the the club, where they could hear the music just fine, than inside. It was where you went to score pot or LSD, which was legal to possess the first year the Vulcan opened, but against the law to distribute. Co-owner White got popped for selling six tabs to an undercover officer in May ‘68.

The Vulcan also showed old movies by the Marx Brothers and the Three Stooges, which is where Shelton said he got the idea for The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers comics. He figured he could make something funnier and relevant to the times. The characters, who would make Shelton famous and well-compensated, debuted as an ad for the no-budget Texas Hippies March on the State Capitol film shown at the Vulcan. The crowd roared at the Freak Brothers, but the movie sucked.

After KAZZ, the most progressive radio station in town, was sold to KOKE in ‘67, general manager Bill Josey Sr. and son Bill Jr. (“Rim Kelly” on the air) started the Sonobeat label to record the best bands from their remotes. After being blown away by Beaumont’s Johnny Winter at the Vulcan, the Joseys signed him and had Sonobeat’s only financial success when they sold The Progressive Blues Experiment, recorded live in an otherwise empty Vulcan in ‘68, to Imperial Records.

The counterculture headquarters was an un-airconditioned hellhole, but capable of magical nights, as 900 heads would pack in to see acts like Big Mama Thornton, the Velvet Undergound, Jimmy Reed, Moby Grape, Mance Lipscomb, the Fugs and all the local faves.

The Vulcan had competition just two months after opening when the Pleasure Dome debuted in Dec. ‘67 with Miami transplants, the Thingies, at the 222 E. Sixth location that housed the Hard Rock Cafe in later years. The Dome lasted only a few months. Same with the Ozone Forest “teen psychedelic club” at 3405 Guadalupe.

Janis Joplin and Big Brother were too big for the Vulcan and so the owners booked them at the Hemisfair Theater in San Antonio on Nov. 21, 1968. But after the singer, who got her start in Austin, canceled the sold-out concert due to illness, promoters lost $3,500. A disgusted Hyde dumped 3,000 posters he had made- one for each ticketholder- into the trash. “We never really recovered,” said Hyde.

The Vulcan tried selling membership cards- at $1 a year- to stay afloat, and Johnny Winter, fresh from his stunning Columbia debut, came back to play a two-night benefit in March 1970. But the club held on only until July that year, (remember: no air conditioning), which left an incredible void in the scene. Then a few weeks later, Shiva’s Head Band manager Eddie Wilson went out the back door of the Cactus Club on Barton Springs Road to take a leak and before him was an abandoned National Guard Armory that was just about the same size as the Fillmore in San Francisco.

316 Congress later became the location of Duke’s Royal Coach Inn, a short-lived, yet beloved punk/new wave club that was a one-year link between Raul’s and Club Foot. It’s currently the home of Patagonia outdoor clothing.

LEGENDARY NIGHT: WHEN MUDDY MET JOHNNY

Johnny Winter was instrumental in exposing the legendary Chicago bluesman Muddy Waters to ‘70s rock audiences, producing and playing guitar on the 1977 comeback album Hard Again and its crossover gem “The Blues Had a Baby and They Named It Rock and Roll.” But the duo had never met before playing on a bill together- Winter’s trio opening- at the Vulcan Gas Company on August 2 & 3, 1968.

On the first night, a Friday, the Waters band didn’t arrive at the Congress Avenue club until after Winter finished. “They did a standard 45-minute set,” Vulcan co-owner Don Hyde recalled. The band wasn’t even wearing their customary suits, as photos by Burton Wilson show, with piano player Otis Spann's glare at the camera underlining the mood of the set. “It was only 10:45 (when they were done), so I asked Johnny if he would play for a couple hours more and he said sure.”

Muddy was still in his dressing room when Winter came back out and blew the doors off the place, a scene captured by rock critic Larry Sepulvado in a review he mailed to Rolling Stone. Waters came out to the side of the stage and his jaw dropped at the albino’s authentic blues style. He found a pay phone backstage and put in a collect call to King Curtis, the sax player and Freddie King producer who was scouting talent for Atlantic spinoff Cotillion. Hyde was standing next to Muddy when he held up the phone for about a minute during Winter’s set and then returned to the receiver. “He white!” Waters exclaimed. “I mean, he REALLY white! Can you believe this shit?”

The next night, the Waters band showed up in sharp suits and played a magnificent two-hour set that left no question about who was the master and who was the protégé. “I think maybe we’d been driving all day Friday and we were tired,” said Muddy’s harmonica player Paul Oscher. “And then we were well-rested on Saturday and got down to business.”

That second night, Muddy called Johnny up for a couple songs to the delight of the sold-out crowd, and a bond built of mutual respect was born. Rolling Stone printed Sepulvado’s review, which led to a crazy bidding war and a $600,000 record deal for Winter on Columbia, the largest for any rock band up to that time.

---------top group image of folks in front of the famous Vulcan, by Belmer Wright who did a lot of photography down there....

What a fantastic story!! Extra big thanks for this one Michael.