In memory of King Curtis, murdered 42 years ago today

Fort Worth native helped make saxophone a lead instrument of rock and roll

It’s a nice, small brownstone with ornate gates on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, just two blocks from Central Park. A young Tom Cruise used to live in the building, as did Robert Downey Jr., when he was with Sarah Jessica Parker. But the front stoop at 50 W. 86th St. holds a tragic memory.

The sax player King Curtis bought this eight-apartment building in 1971, just after he got off a tour with Aretha Franklin. After more than a decade as a first-call session player in Manhattan, he’d saved his money and bought his piece of the island. On August 13 of that year, Curtis had gone downstairs to check on a recently-installed air conditioner that didn’t seem to be working and he saw a couple of junkies hanging out on his steps. The neighborhood was much different than it is today. Heated words led to a scuffle and then a fistfight with 26-year-old ex-con Juan Montanez. But the junkie had a shiv and plunged it into the heart of the dynamic tenor sax player from Fort Worth. Curtis got the knife away and stabbed his attacker, who was arrested at Roosevelt Hospital that night and eventually sent back to prison. But King Curtis was pronounced dead on arrival. He was 37 years old and on the verge of becoming to Aretha what Lester Young was to Billie Holiday, what Maceo Parker was to James Brown. He had the honkin’ horn that clicked with the volcanic voice; they took each other to magical places.

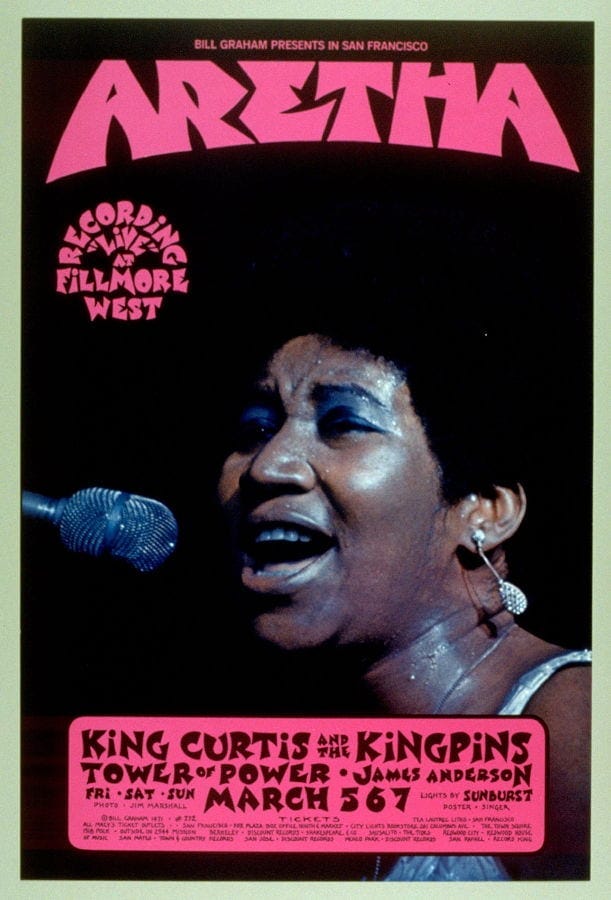

“You heard King Curtis tonight, heard us do our thing together,” the great Lady Soul said at the end of three exhausting and delirious nights of music in March ’71 which have been preserved on a pair of highly-recommended Live at the Fillmore West albums. “We’re gonna do our thing for years to come, I imagine.” But just five months later, the master of the shrieking, stuttering, soulful sax sound had been silenced.

More than 2,000 people attended King Curtis Ousley’s funeral at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church in Manhattan, with Rev. Jesse Jackson delivering the eulogy and Stevie Wonder tacking the name of King Curtis onto his rendition of “Abraham, Martin and John.” Aretha Franklin was there, too, singing her sax man home with a gospel song, “Never Grow Old.”

His killer pleaded guilty to second-degree manslaughter and received a seven-year sentence, disgustingly light when you consider what he also robbed the world of.

But it’s not as if King Curtis hadn’t left his mark. You can hear his influence every time the Saturday Night Live band kicks off another episode. Like his former employer Sam Cooke, who also died senselessly in his 30s, King Curtis packed quite an amazing career into his shortened years. But we’re left wondering where else his horn would’ve led him.

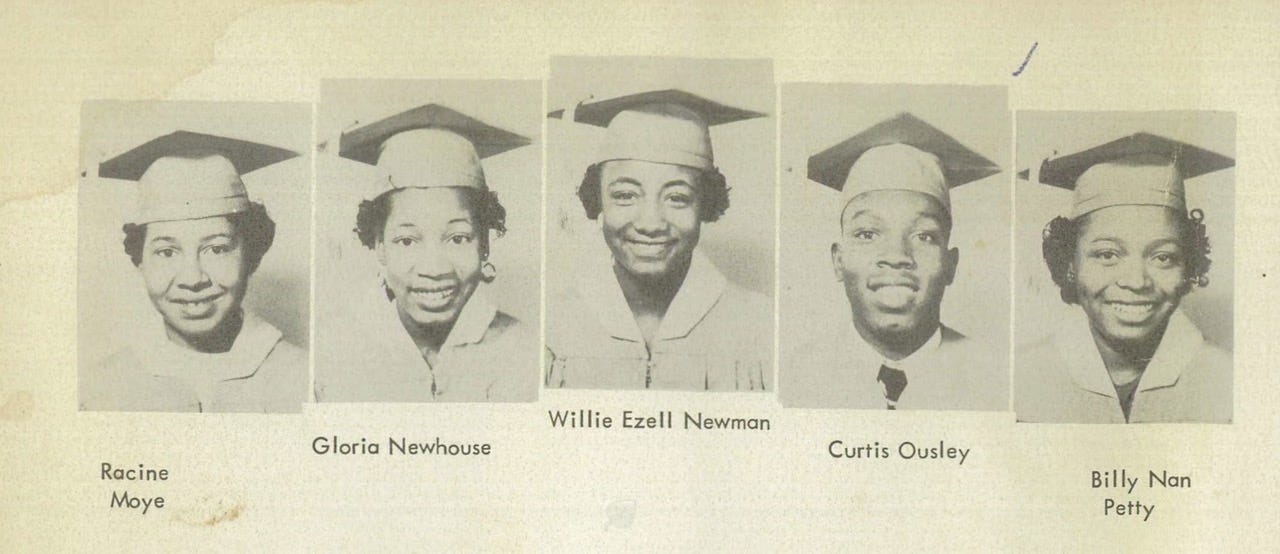

Curtis Ousley, born in 1934 in Fort Worth, went to the same I.M. Terrell High School as jazz sax legends Ornette Coleman and Dewey Redman. Curtis was a proponent of the Texas tenor sax sound pioneered by Illinois Jacquet and Arnett Cobb. Like those Houstonians and Herschel Evans from Temple, King Curtis served his apprenticeship in the band of Lionel Hampton, moving to New York City at age 19.

I.M. Terrell Panther Band: ‘Separate But Superior’

Because of his versatility and ability to frame the feel of a song, Curtis became an in-demand studio player and in 1958 recorded one of the most recognizable sax parts ever with “Yakety Yak” by the Coasters. Curtis came to define Atlantic Records’ rock ’n’ soul sound, as label co-owner/producer Jerry Wexler called on him for hit-producing sessions with Percy Sledge (“When a Man Loves a Woman”), Clyde McPhatter (“A Lover’s Question”) and Franklin (“Respect”). He also recorded with Buddy Holly, Bobby Darin, Wilson Pickett and the Shirelles. Little known fact: King Curtis and his band the Kingpins opened for the Beatles at Shea Stadium in 1965. His last session was on the Imagine LP by John Lennon, who would be murdered, nine years later, just across Central Park from where Curtis was killed.

“King Curtis was my main man,” Rolling Stones sax player Bobby Keys said in 2012. “He had this totally unique phrasing that was almost like country fiddlers.” Keys then hummed the sax part of “Yakety Yak” while miming a violin being played.

As a high schooler near Lubbock who ran errands for Buddy Holly and the Crickets, Keys once picked up Curtis at the airport in Amarillo and drove him to Clovis, New Mexico for sessions with Holly that produced “Reminiscing,” as well as two tracks with Waylon Jennings on vocals.

During the late ’50s, the sax was becoming the lead instrument of rock ’n’ roll and Curtis blew the flamboyant sparks that producers wanted. But he also had instrumental hits under his own name, including “Soul Twist,” which topped the Billboard R&B chart in 1962, “Soul Serenade” (1964), “Memphis Soul Stew” (1966) and “Ode to Billy Joe” (1967). Session work was becoming so lucrative that Curtis and his earliest incarnation of the Kingpins, which included fellow I.M. Terrell alum Cornell Dupree on guitar, rarely toured.

But they made an exception when Sam Cooke took them out on the road in 1963, the year before the singer’s death. Sam and Curtis were kindred spirits, according to Cooke biographer Peter Guralnick, who observed that, like Cooke, Curtis was articulate, outgoing and took his music seriously. King Curtis also liked to gamble; the dice would roll for hours after each show. You couldn’t get such action in the studio. That tour is brilliantly represented by One Night Stand! Live at the Harlem Square Club, 1963, which some critics have called Cooke’s best LP. It’s his answer to James Brown’s Live at the Apollo release, with the explosive Kingpins urging the singer to cut loose like he did during his gospel days. Cooke tips his hat to Curtis on the set-closing “Havin’ a Party” with the line “play that song called ‘Soul Twist.’”

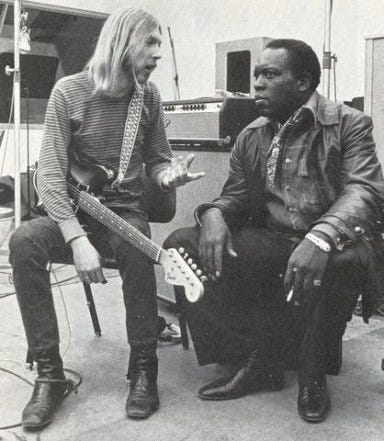

Curtis’s work with Aretha would prove to be even more enduring. His sax was with her from her very first album on Atlantic, 1967’s I Never Loved a Man (the Way I Love You), which producer Jerry Wexler had hoped to cut entirely at FAME studio in Alabama, with the same session players that had cut hits with Wilson Pickett and Clarence Carter. Although a great talent, Aretha had been a disappointment at Columbia Records in the years before signing to Atlantic, but Wexler knew he had to get her down to Muscle Shoals. But after the first day of recording, Aretha and her volatile then-husband Ted White were on a plane back to Detroit. White was on edge about his wife recording with an all-white band in George Wallace country and ended up getting in a drunken fistfight with studio owner Rick Hall at about 4 a.m.

The sessions were moved to NYC, where Wexler flew up the Muscle Shoals guys, including the great rhythm section of drummer Roger Hawkins and bassist David Hood. The first song they recorded in Manhattan was Aretha’s version of Otis Redding’s “Respect,” with Curtis taking a 16-second solo. It would become her first No. 1 and remain a signature song.

Curtis loved Aretha’s piano style and got her to play on a 1970 Sam Moore record (Plenty Good Lovin’) he was producing, something Lady Soul rarely did. But she had an affinity with her bandleader that she had with few people. “Curtis was noble, ballsy and streetwise like nobody I ever knew,” said Wexler, who often used the bandleader as a go-between with a moody Aretha.

The 1971 Kingpins, whose membership included guitarist Dupree, bassist Jerry “Fingers” Jammott, the polyrhythmic prince Bernard Purdie on drums, plus Billy Preston on the Hammond B3 organ and the Memphis Horns, had a similar effect on Aretha Franklin at the Fillmore West, coaxing a majestic performance from the unbridled soul shouter. “Respect” gallops out of the gate as if fueled by pure adrenaline, “Bridge Over Troubled Water” wrings the soul like never before, “Eleanor Rigby” struts over Franklin’s electric piano lead and “Dr. Feelgood” is impossibly lowdown.

At one point, someone from Aretha’s entourage spotted Ray Charles seated in the back of the crowd, and the Queen of Soul called up her male counterpart in the monarchy for a loose and inspired 19-minute jam on “Spirit in the Dark.” It was a strange period for Franklin, who from 1967-69 recorded three of the most remarkable albums in music history.

At the advent of the ’70s, however, Franklin was in a bit of a sales slump, with a live album and a jazzier project going nowhere. Although her 1970 Spirit in the Dark album was one of her best, with the Franklin-penned title track making creative strides, it also registered disappointing sales. Had Arethamania died out? Wexler decided that the key to his prized diva’s rebound was to connect with the hippie rock audience that had so wildly embraced Otis Redding at Monterey. The headquarters of the counterculture was Bill Graham’s music hall the Fillmore, so Wexler booked Aretha into the 2,500-capacity venue for three nights. To make the shows financially feasible, a live recording was planned.

Although Franklin had a touring band, Wexler convinced her to leave them in Detroit in favor of the all-star Kingpins, the tightest band in R&B. The opening show of the three-night stand was the first time Franklin and the Kingpins had played together, though she had just gotten out of the studio with Purdie and Dupree on sessions that would restore Franklin’s perch at the top later in ’71 with “Rock Steady” and “Spanish Harlem.” Franklin’s Live at Fillmore West and Curtis’ album of the same name (which came out a week before his murder), are landmark recordings, finding true geniuses of soul adapting their sound for the rock crowd and, in the process, creating the funky jam band sound. Although many have tried to duplicate what went on at the Fillmore West on March 5-7, 1971, nobody comes close. You can keep your 20-minute versions of “Feelin’ Allright,” performed by Meters/Grateful Dead wannabes. Ears that know better will take Curtis and the band’s rock-funk throwdowns on Buddy Miles’ “Them Changes,” Preston’s monster organ take on “My Sweet Lord” and a sultry, percolating version of “Mr. Bojangles” that should be one of Jerry Jeff Walker’s proudest moments as a writer.

The Live at Fillmore West albums are a jubilant study in musical communication, of instinctively finding a groove and building the intensity. Three-minute songs are stretched out to 10 minutes without any sense of overindulgence. These players were having a blast and the audience knew it, cheering them on with near-religious zeal. Listen to King Curtis today if you can. Play the records in order — Curtis first, then Franklin — and don’t dwell on the stupidity of the tragedy that took him away. Listen to just how alive King Curtis was five months before his death. Breathe in that thick saxophone smoke and dream of what might have been.