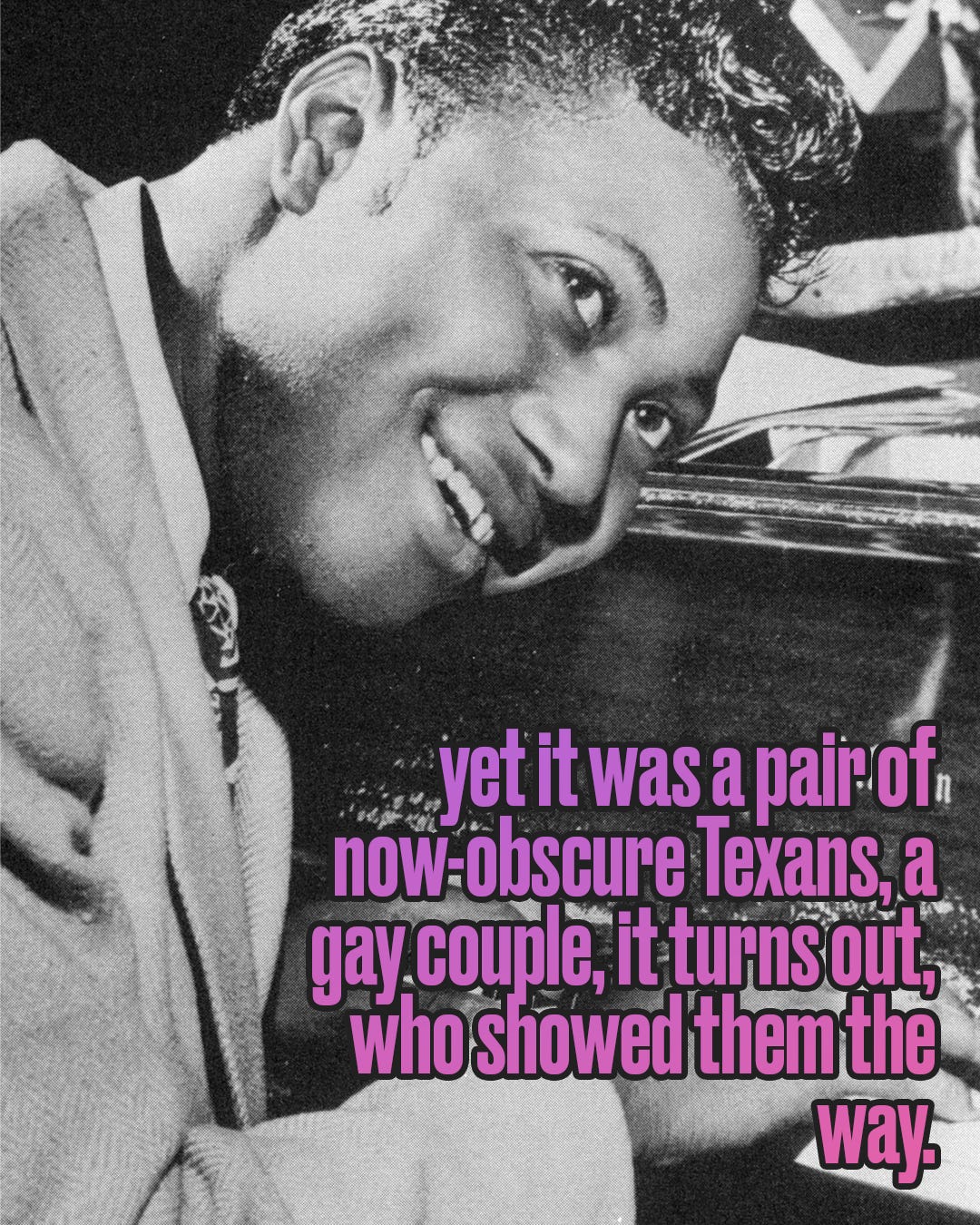

IVORY GHOSTS: Charles Brown and Amos Milburn

Texas R&B piano greats influenced rock 'n' roll, which steamrolled their careers

by Michael Corcoran

Amos loved his whiskey and Charles was a gambling fiend, so the Sportsman Club in Newport, Kentucky, just over the Ohio River from Cincinnati, was a place they could be together with their vices night after night. They also played and sang at the illegal casino, but it’s not like they had a choice.

Charles had a problem with horses that wore numbers and little men, but you didn’t borrow money from Frank “Screw” Andriola unless you had a “can’t miss” tip. The only sure thing, however, ended up being a nightly appearance at the mobster’s Sportsman Club for as long as it took to repay that wager and future debts. In August 1961, the vig gig neared the one-year mark.

That’s the month Hilton Owens started hanging around the Sportsman, which catered to a black clientele. The first night he couldn’t believe the lobby placard that said recording artists Charles Brown and Amos Milburn were playing in the lounge. These guys had number one hits! His job as an undercover Internal Revenue Service agent was to infiltrate and observe the gaming operations, but on hearing Milburn’s “Chicken Shack Boogie,” the first thing Owens investigated was where that fat groove was coming from. When Charles Brown sang “Black Night” during the next set, the tax man figured the roulette tables could wait.

Brown’s songs of romantic yearning were undoubtedly a boon to Andriola’s bordello next door, while Milburn’s sets spurred bar sales. The younger of the two men had become so associated with drinking songs after “Bad, Bad Whiskey” topped the charts in 1950, followed by “Thinkin’ and Drinkin’,” “Let Me Go Home, Whiskey” and the original “One Scotch, One Bourbon, One Beer,” that Amos lined shot glasses on the top of his upright when he played.

“You guys should be headlining at the Apollo!” Owens told the singing ivorysmiths during a break. It had been years since they'd had a hit, but Brown and Milburn were still in their thirties, with skills undiminished. One night, according to his memoir One of the First, Owens approached Charles with a concerned look. “How long would it take you and Amos to get out of here?” The Sportsman was about to be raided as part of new Attorney General Robert Kennedy’s war on mob-controlled activities. “I heard the axes hit the front door and we hid in the ceiling,” Milburn recalled in a recently unearthed 1979 interview, conducted just nine months before his death of a heart attack at age 52.

Charles and Amos looked down from the rafters on that night of August 22, 1961, to see Andriola being led away in handcuffs. Their forced residency was over. But where were they going to go tomorrow night?

At least the pair got a good song out of their dicey situation. In January ’61, Brown and Milburn recorded “I Want To Go Back Home” as a duet for Cincy’s King label. A Sportsman-inspired rewrite of an earlier single on Ace, the record didn’t chart, but Sam Cooke dug it, which was just as good. The soul superstar wanted to re-record the number as a duet with Charles, but on the day of the 1962 session in Los Angeles, Brown went to the racetrack instead. Faced with a studio of musicians on the clock, Cooke changed most of the words into “Bring It On Home To Me” and leaned the melody just far enough to make it legally his own. Lou Rawls sang what would’ve been Brown’s answer part on the classic.

You don’t get famous for what you start. Today, Brown and Milburn – whose suave musicianship helped transform “race records” into the more honorable designation of “rhythm and blues” in the late-‘40s – are far less known than those they inspired.

After Fats Domino rocketed out of the Ninth Ward of New Orleans and onto the top of the R&B charts with first single “The Fat Man” in 1950, he was routinely asked about his influences and acknowledged one name above the others. “I first heard (piano) triplets on an Amos Milburn record,” Domino said in his 2006 biography Blue Monday: Fats Domino and the Lost Dawn of Rock N’ Roll. The three-notes-to-a-beat sound he discovered on Milburn’s 1947 record “Operation Blues” turned up on such hits as “Blueberry Hill,” and would become a foundation of New Orleans R&B – and, therefore, rock n’ roll. Fats said Amos was “the only blues singer I tried to sing like,” and he even hunched over the piano with a cherubic grin like his hero from Houston.

The model for a teenaged Ray Charles, meanwhile, was Charles Brown of Texas City, who helped define West Coast Blues with a brooding, yet always elegant style that spoke to African Americans hopeful for a better life after World War II. “Charles Brown was a powerful influence on me in the early part of my career, especially when I was struggling down in Florida,” Charles noted in the Brother Ray bio by David Ritz. “I made many a dollar doing my imitation of his 'Drifting Blues.’ That was a hell of a number.”

Ironically, the intensified music of Brown’s and Milburn’s protégés steamrolled the ‘78s of jumpin’ and swayin’ blues that had given them a jukebox education. Teenagers in the ‘50s were learning to live in the moment and had no use for the musicians who anticipated rock n’ roll. Brown and Milburn both hit a cold streak in 1954, after “Rock Around the Clock” by Bill Haley and the Comets changed everything. From 1946 to 1953, Brown and Milburn had more than 15 hit R&B singles each. After that, they had none.

Aladdin Records tried to make its former chart-toppers relevant again by booking them into Cosimo Matassa’s hit factory in New Orleans in Sept. 1956, backed by the musicians who’d recently played on number one records by Domino and Little Richard. But the results were disappointing, financially, at least. Brown recorded 11 tracks in one day, but only three were released. Milburn re-cut “Chicken Shack Boogie” in the same session, and although the recording blows away almost anything else on the charts in ’56, few ever heard it. “It was too fast for R&B and too slow for rock n’ roll,” Milburn reasoned of radio’s rejection of the French Quarter version of his signature tune. You had to sing like your hair was on fire in 1956 and Charles and Amos were too cool for that.

One has to wonder if the music biz buzz about the Brown/Milburn relationship might’ve also had something to do with why they fell out of favor. It was known in their musical circle that Brown and Milburn were gay – a fact confirmed through interviews with their musicians, an ex-wife and a manager/lawyer. “Various older musicians told us they were a couple,” said guitarist Danny Caron, Brown’s bandleader from 1987 until the pianist’s 1999 death at age 76. “But the public didn’t know about it.” Brown’s manager Howell Begle, who worked for the estate until early 2019, when he died after a skiing accident, said he’d heard the pair of piano greats were together during the years they were on King Records, from 1960-63. But he never heard that from Brown himself. “Charles and I were very close and he never once talked about being gay,” said Begle.

Brown’s ex-wife Mabel Scott, herself a popular singer/pianist, was frank about her relationship with “the great love of my life” in an interview with RJ Smith for his 2006 book The Great Black Way. “He was a homosexual,” she said of Brown, “and the men drove me crazy.” The couple’s splashy showbiz wedding of 1949, which made the cover of Ebony, was the back-page divorce of '51.

Milburn was outed by his longtime guitar player Texas Johnny Brown in a 1987 interview published in the book Texas Blues. “He was gay, but easy to get along with,” said Brown, revealing a slight discomfort.

Brown’s sexual orientation “wasn’t a secret to us,” said 85-year-old blues belter Carol Fran, whose husband, esteemed Houston guitarist Clarence Holliman (1937-2000), played in Brown’s band for many years. Everyone called Holliman “Gristle” after an infamous incident, which Fran confirmed, on the road with Brown. In a moment of misplaced lust one night, the singer went to grab the guitarist’s crotch and had his hand slapped away. “Ah, man, it’s just gristle,” Brown remarked. Holliman wore the nickname like a badge.

Neither Brown nor Milburn ever publicly admitted to being gay because it just didn’t make financial sense to ruin the fantasies of so many female record and ticket buyers. There was also the choice between the closet and the cell. Sexual activity between persons of the same gender was a criminal act in all states until the mid-‘60s.

The pair came off as domestic partners in interviews, with Brown praising Milburn's dinner chops. “He made chitlins and neckbones and anything you wanted. I loved his way with food,” Brown said in 1993, but later complained about his roommate’s drinking. ”Amos and I lived in the same apartment and he was out partying every night, acting like the world was coming to an end,” said Brown, who drank only rarely.

Brown and Milburn’s close association goes back to 1946, when Charles was ridin’ high with “Drifting Blues” and Amos, just back from the war, was the new boogie-woogie prince of Houston. “Charles was an admirer of mine even before I moved to L.A.,” Amos told bluesologist Charlie Lange. When he sang blues ballads, it was obvious Milburn also looked up to Brown.

The eighth of 12 children and the first born in Texas to Louisiana natives, Amos was a natural on the piano. His musician brother Frederick, older by 12 years, showed him a few things and he quickly took off from there. There would be no church for young Amos, who found his religion hanging outside Third Ward juke joints in the late ‘30s.

According to the liner notes of Mosaic’s 1994 set The Complete Aladdin Recordings of Amos Milburn, the piano prodigy had an early act billed “He-Man Martha Raye,” performing novelty numbers he’d heard the comedic hoofer sing in movies like 1941’s Navy Blues. Raye joined the USO in 1942 and in November of that year a 15-year-old Amos became 17 on his paperwork and enlisted in the Navy. He was assigned to the food crew of a ship based in the Philippines, and it’s not known if Seaman Milburn ever met “The Big Mouth,” but you can be sure he entertained the fellas with his Martha routine. And he certainly had access to a piano, because just a month after returning to Houston from the Navy in October 1945 to attend Amos Sr.’s funeral (pneumonia), he was playing Sid’s Ranche nightclub, the hottest chicken shack in Houston. Six months later Milburn opened for T-Bone Walker at Don Robey’s Bronze Peacock.

The big three of boogie woogie piano – Pete Johnson, Albert Ammons and Meade Lux Lewis – were big influences on Milburn, as were jazz pianist Art Tatum, R&B great Louis Jordan and Nashville’s Cecil Gant, “the G.I. Sing-sation,” who also moved between ballads and boogie-woogie. But the most significant musical moment of his life as a listener, he’s said, came when his ship pulled into the harbor at Long Beach, California at the end of the war and the radio picked up “Blues at Sunrise” by Ivory Joe Hunter. It was a new day on the coast and Milburn heard a smooth and soulful world he wanted to be part of. Backing Kirbyville, Texas native Hunter on the lowdown 1945 recording were Johnny Moore’s Three Blazers with Charles Brown playing that sly, sparkling piano that Amos took right to his heart.

African-American musicians from Texas didn’t flock to Memphis or Chicago, they went to South Central LA – a Harlem with palm trees – bringing the heavy blues and gospel feel from home, but refining it with inventive instrumentation and silken vocals. In the mid-‘30s blues guitarists T-Bone Walker from Dallas, Rockdale’s Pee Wee Crayton and Austin-born Johnny Moore came looking for more opportunities in a relaxed racial climate and mined the Central Avenue strip for gigs. Nat Cole, from Chicago, was still the King on the LA club scene, but even he had an essential Texan – Johnny Moore’s younger brother Oscar Moore – who crafted the small combo jazz guitar style during his 10 years (1937-’47) with the King Cole Trio.

Charles Brown made it to L.A. in late 1944 and quickly drew notice by winning a talent show at the Lincoln Theater with a wry segue of Earl Hines’ “Boogie With the St. Louis Blues” into “Warsaw Concerto.” Brown, who’d been a high school science teacher in Texas just a year prior, proved to be the kind of cultured bluesman that Central Avenue was looking for. He was hired on the spot to play piano at Ivie’s Chicken Shack (ironically, an upscale joint), where he rotated with his best friend from Prairie View A&M (class of ’42) Richie Dell Archia. The sister of noted jazz saxman Tom Archia, Richie got Charles that teaching job at Carver High in Baytown right out of college because her father was the principal. But sheer talent is what opened the doors for Brown in the music field.

Johnny Moore was in the audience at the Lincoln the night Brown dazzled on those piano instrumentals. His band was a Blazer short, needing a piano player who could handle lead vocals, so Moore tracked down Brown, who was working during the day as an elevator operator at a department store. Asked to audition, the pianist said he wasn’t a vocalist. But Charles gave it a try, singing 1941 hit “Embraceable You” by his favorite singer Helen “O’Connell. The Blazers were Three again and went to work right away, making music that made babies.

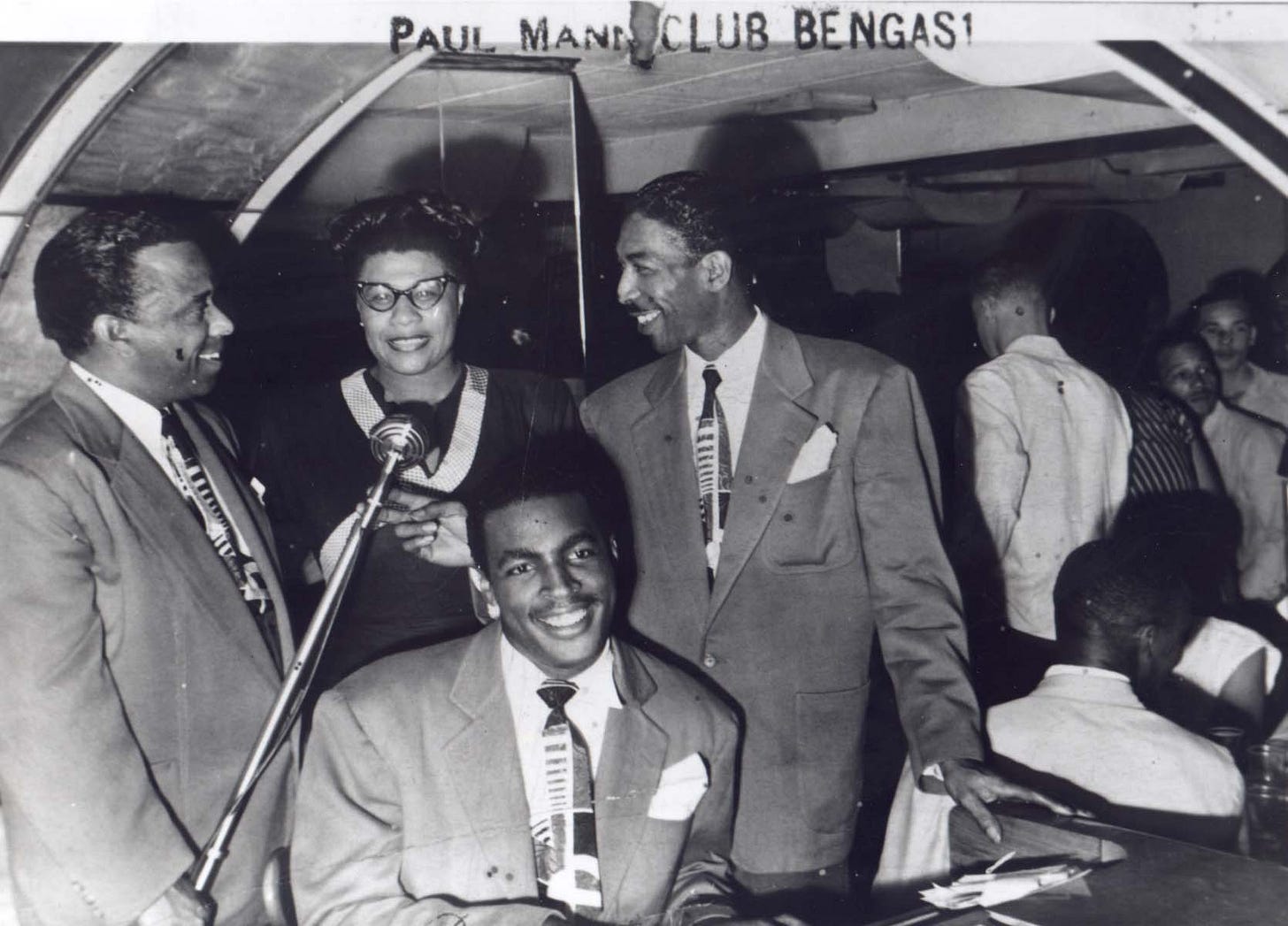

Milburn was discovered at San Antonio’s Keyhole Club in the summer of ’46 by Lola Ann Cullum, the 50-year-old wife of a prominent Houston dentist. Active in Houston black society, the Cullums made the Houston Informer front page when they put up W.C. Handy, “Father of the Blues,” in March 1946. The visit seemed to have strengthened musical aspirations in Lola Ann, whose life of transitions began when she went from Weimar farm girl to the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority at Howard University circa 1914. Cullum trekked to the Keyhole, a 350-capacity former movie theater at the corner of Pine and Iowa Streets, that summer night to see Duke Ellington. Way down on the bill was Milburn, who played his own set and backed the brother-sister dance team of Mack & Ace. “When you come back to Houston,” Cullum told 19-year-old Milburn, “let’s make some recordings.” Lola Ann had just bought a Soundmirror tape recorder, the first available to the public, and was eager to get in on the postwar R&B explosion.

Cullum had a slow blues tune she’d been messing around with called “After Midnight,” which Milburn finished on the Cullum’s baby grand piano and sang in the style of Charles Brown. The demo, recorded on paper-backed magnetic tape, appealed to the Mesner brothers, Leo and Eddie, who had the hit with “Drifting Blues” when their L.A. label was called Philo. They were looking for the next Charles Brown, but what the renamed Aladdin Records signed was the first great rock n’ roll piano player. Milburn’s roadhouse romper “Down the Road Apiece,” from the maiden Milburn session in September 1946, got the juices flowing like a first kiss. When Chuck Berry covered the tune in 1960, Milburn’s record was the source, not the tamer 1940 original by the Will Bradley Trio. To give it some extra grease, Milburn scat-hummed over his lightning right hand, while his left kept a furious beat. Boogie-woogie had been popular for almost 20 years, but no one had heard it played as spectacularly.

“Mrs. Cullum,” as everyone called her, brought her next discovery Lightnin’ Hopkins to Aladdin in November 1946, and went two-for-two as a talent scout when Hopkins hit the Top Ten in 1949 with “T-Model Blues.” A female manager in the 1940s was rare, indeed, and Cullum no doubt met with prejudice. But she was sharp, educated, connected and used maternal instincts to get the most out of her acts and those who could benefit them. A “hands on” rep, she bought Milburn’s clothes and helped him and Aladdin staff producer/saxophonist Maxwell Davis choose the songs to record. She even drove the band on the road. But when Cullum’s management contract was up for renewal in 1949, the Mesners convinced Milburn he was too hot for her to handle. A heartbroken Cullum started a record label in Houston, Don Robey’s turf, but after releasing just one single by Honeyboy Edwards in 1951, she went back to being a fulltime dentist’s wife. The yearly, dwindling, royalty checks as co-writer of “Chicken Shack Boogie” and “Hold Me Baby” were all she had to show for her time in the music biz.

While Lightnin’ Hopkins also went back to Houston, Amos had found his paradise in L.A. He was named #1 R&B jukebox artist of 1949, at age 21, landing four singles – “Chicken Shack Boogie,” “Bewildered,” “Hold Me Baby” and “Roomin’ House Boogie” – on the list of the 30 most-played ‘78s of the year. Milburn repeated as jukebox champ in 1950, with Brown taking the top spot the next year with the haunting “Black Night” spending 14 weeks at #1.

Aladdin was one of the big four independent R&B labels on the West Coast after WWII – along with Modern, Imperial and Specialty – and Milburn and Brown were its biggest stars. Both were sensational piano players, but their music was two sides of the R&B coin, with Milburn’s joviality the flip of Brown’s entrancing melancholy. Charles was classically trained, Amos couldn’t read music. But they were both bluesmen and a natural pairing on their constant co-headliner tours, creating a range of moods.

“The first night me and the boys played the Apollo, the crowd was wondering ‘what are these Texas cowboys gonna do up there?’,” Milburn recalled in 1979. “The curtains parted, we came on to ‘Chicken Shack Boogie’ and it looked like the roof was gonna blow off!” The best joints are generally the most dangerous, but you take your chances, was the song’s message, which went over especially well on 125th Street. Milburn had played enough chicken shacks in Outskirts, Texas to have seen it all by a young age and he poured all that reality over a song prominent bandleader Johnny Otis called “one of the greatest records of all time.”

Charles Brown kept his piano blues in a more laid-back, swankier locale. Matinee idol handsome, with a voice like an aching, lingering whisper, Charles had women in front of the stage practically humping the legs of his piano. Even his holiday classic “Merry Christmas, Baby” (1947) exuded sexuality. Topped by a toupee or beret, Brown liked to wear matching mink capes and neckties and in private was as flamboyant as Little Richard, according to Ruth Brown. But onstage Charles was the smooth, sexy Captain of a forlorn ship, looking for a harbor.

Originally dismissed by Metronome as “closely reproducing every nuance of Nat King Cole’s voice and piano,” Brown actually had a unique style that breaded his languid voice with a heavy gospel past. Baptist Church choir director Swannie Simpson, whose daughter Mattie gave birth to Charles at age 20 and died the day before she turned 21, raised her grandson in Texas City with his grandfather Conquest Simpson. (Coincidentally, the Simpsons were from Opelousas, La., as was the Milburn family.) After Charles got good on that church keyboard, Swannie paid for lessons for him to learn classical piano and stayed on his ass, sometimes with a switch. “His grandmother used to beat the hell out of him, but he loved her,” said Caron, who listened to Brown’s stories of his upbringing on the long bus rides between gigs in the ‘90s. He sometimes recounted detailed interactions with his mother, though she died when he was six months old.

Brown’s father Mose drank heavily, chased women and neglected his son. Brown told Caron that his father once left him, at age three or four, in the parlor of a cathouse while Mose went upstairs. “Charles blamed his father for his mother’s death, giving her syphilis,” Caron said. The 1923 death certificate of Mattie Brown lists syphilis as a contributing factor to the main cause, exhaustion from gastroenteritis (stomach flu.) “Mose had moved to the Panhandle to work and he came back to Texas City to get Charles. That’s when his car got stuck on the railroad tracks and he was killed by a train,” Caron continued. Mose Brown died in 1928, when his son was 5 and a half. “Charles told me that he wondered how his life would’ve turned out if his father took him away from his grandparents. He said he certainly wouldn’t have been a musician.”

But, then, he also might not have turned into a degenerate racetrack gambler, known to drop his last $1,000 on a single race. It was Johnny Moore, 16 years his senior, who introduced Brown to pari-mutuel wagering, an instant obsession explored in the Blazers’ 1946 single “Race Track Blues.” Cash was always an issue between Moore and singer Brown, who was the star of the group no matter what the damn marquee said. When the guitarist sold "Drifting Blues" to Philo for $800, Brown was incensed. He wrote that song while a student at Central High in Galveston, yet had to share credit with the other two Blazers. Worse, Moore taking the short money on the future R&B Record of 1946 cost Brown hundreds of thousands of dollars he could’ve turned into millions at the racetrack.

Brown went solo in 1948 and hit the top five with “Get Yourself Another Fool,” whose title could’ve been aimed at Moore. His first #1 smash was 1949’s “Trouble Blues,” which Sam Cooke covered in 1963 on the classic, Brown-influenced LP Night Beat. Lieber-Stoller’s first hit “Hard Times,” was Brown’s last in 1952, with the title presaging the years ahead, as his records flopped, his booking agent jumped ship and the union hounded him for dues.

“There might have been some homophobic agents or club owners,” said Caron. “But the gambling hurt Charles’ career more than anything. You couldn’t give him any money. It would be gone in an hour.”

Both dropped by Aladdin in 1957, Brown and Milburn were drifting without a sail. But the pair finally caught a whiff of luck in Cincinnati in September 1960 when King Records owner Syd Nathan, also surprised that the R&B piano icons were playing some local gambling den, sent for Brown and Milburn. “Syd Nathan said we needed to write a new Christmas song,” Milburn recalled in 1979. “Me and Charles were living in the same hotel room, so he went to one side to work on his song and I went to the other side to work on mine.” Brown’s crooner “Please Come Home for Christmas” became the seasonal radio hit (especially after the Eagles covered it in 1978), but there’s nothing “B” about the flip side – Milburn’s rollicking “Christmas (Comes But Once a Year),” with its then-inventive ska-styled beat. Brown covered it on his 1961 Christmas album for King.

The pair split up, at least label-wise, when Milburn left King for Motown in 1963. In another case of bad timing, his Return of the Blues Boss LP was buried under the emergence of labelmates Marvin Gaye, the Supremes and Stevie Wonder, who had their first big hits that year.

Brown and Milburn both got married in Ohio in the mid-‘60s, with Brown moving to Columbus to be with the recently widowed Eva McGhee, who “owned the largest garage in town,” Brown told Living Blues magazine in 1994. Milburn relocated to Cleveland with third wife Ann Marie Macarol, just six years out of Euclid High. (He had earlier been married in ’46 and ’54.) Though the Ohio marriages didn’t last, they seemed to have provided some needed separation between the codependents. Brown moved to the West Coast after his divorce, playing jazzy organ in lounge trios and reconnecting with Johnny Moore, while Milburn stayed in Cleveland, where he remained a regional star.

In 1969, while playing Satan’s Den in Cincinnati, Milburn’s left hand stopped listening to his brain. Instead of that steady boogie-woogie bass line, there was a flail of fingers unsure where to go. “When I went to tell the club owner, he said, ‘Amos, your mouth is crooked.’ I had a stroke right there onstage.”

Milburn had recovered sufficiently to play a "Battle of the Blues" with Brown at a political fundraiser in 1970 at the Viking Lounge in Cincinnati. But later that year, Amos had a second stroke that left him wheelchair-bound and severely piano-challenged. Doctors ordered 42-year-old Milburn to quit drinking after the first stroke, but he just couldn’t leave the scotch alone. “You know how stupid you can be sometimes? I went right back to ‘Bad, Bad Whiskey’," he said. "I was never a dope fiend, but I drank Canada dry.”

On Milburn’s final session in 1976, re-recording “One Scotch” for a West Coast R&B compilation, producer Johnny Otis had to play the left-handed parts on the piano.

While that hypnotic southpaw groove had always been a Milburn strength, Brown’s trademark was a glistening right hand that played off his vocals. Johnny Moore made him practice with his left hand tied behind his back because the Blazers had a four-stringer in Eddie Williams and Brown’s instinctive bass patterns were unnecessary. His left hand was relegated to foundation chords in the Blazers, but later in his career, Brown showed he could play it all, like the missing link between Liberace and Little Richard. “Charles was a piano savant,” said Caron. “He could play anything in any key instantly, and never forgot any tunes.”

A fan of Brown’s vintage mellow steam, Caron had doubted aloud that the singer was still alive when he and fellow musician Michael “Hawkeye” Herman were spinning old records in Berkeley, California one afternoon in the mid-‘80s. “Charles Brown lives a couple blocks from here,” Hawkeye said. An incredulous Caron found the R&B great in Section 8 housing, making extra scratch singing “Just the Way You Are” and “Bridge Over Troubled Waters” in piano lounges in the Bay Area. “He had a little spinet piano at home, but his chops were still great, his singing still great.” After playing a Christmas gig with Brown, Caron convinced him to revisit his career more seriously and leave the Billy Joel covers to the hacks. “If you put together a really good band, this could work.”

It did. A residency at New York City club Tramps led to the lauded album One More for the Road, semi-released on Blue Side in 1986 and reissued on Alligator in ‘89. That year Bonnie Raitt, fresh from her Nick of Time Grammy haul, took Charles on the road for 45 dates as her opening act. The comeback was on. “Charles always called Bonnie his ‘Rising Sun’ and Ruth Brown his ‘Setting Sun,’” said publicist Joan Myers, who worked with Raitt and both Browns at the time. “He was just so gracious and thankful for every little thing that went his way.” Brown received three Grammy nominations in the ‘90s for LPs on Rounder’s blues offshoot Bullseye Records.

Playing the 1995 wedding of Ted Danson and Mary Steenburgen was not only a nice payday, but attendees Tom Hanks and Bill and Hillary Clinton became huge fans. In ‘97, the National Endowment for the Arts awarded Brown a National Heritage Fellowship, and the next year he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as an early influence. Brown passed away a month before the induction, from congestive heart failure at age 76, so Bonnie Raitt accepted the honor for her good friend, “the Sequoia of the Blues,” whose music she called “the most astounding mix of delicacy and roar.”

Charles Brown had a celeb-heavy Los Angeles funeral in January 1999, with preacher Solomon Burke presiding. “When I was coming up, I just wanted to be Charles Brown,” Little Richard said in the eulogy. “Then, later on, I just wanted to be Ruth Brown.” It was not a sad affair. During the viewing, singer-pianist Hadda Brooks, a 1940’s label-mate, slipped a black eyeliner pencil in Brown’s suit jacket inside pocket. He never went anywhere without one.

The reception was held at the deceased’s favorite place on earth, Hollywood Park race track. A banner across the entrance read “Welcome Home Charles Brown.”

There was no such charmed ending for Milburn, whose last decade was spent in a wheelchair, with use of only one arm. His daughter Elaine Milburn Monroe, 71, said Charles Brown rarely, if ever, visited during those years, when Amos embraced religion with a passion he once gave to the blues. After he passed on January 3, 1980, Milburn’s four-inch obit in the Houston Chronicle was no more detailed than the one for a local banker who died the same day. There was almost no national attention for the passing of a man who recorded rock n’ roll records eight years before Bill Haley (whose own comeback was also nullified by drink).

Any addiction is just masking another issue: a painful upbringing, low self-esteem, depression, or maybe having to hide a romance that society condemned as a disease, an aberration. Singing all those songs about women when it’s a man you love can take its psychic toll. But sometimes the same thing that drives people to alcohol or gambling also makes them master a discipline. If you can make sense of those 88 keys of black and white, through practice and single-minded devotion, then you can find a measure of peace and power in your crazy world. If only until the song’s over.

Amos and Charles were victims of their vices, and of times that changed too fast or not at all. But for a while, they were the most talented couple in America.

Originally published by the byNWR.com website, where it was no longer available on Charles Brown’s 100th birthday this week.

What a wonderful read...thank you! I've been a fan of Charles Brown for a very long time.

As I'm working on a cover version of Charles Brown's "Black Night", I've been searching for background info on him .... and boy did I find it here. This essay is a real gem. Thanks for writing.

By the way, do you know who played guitar on the original recording of Black Night?