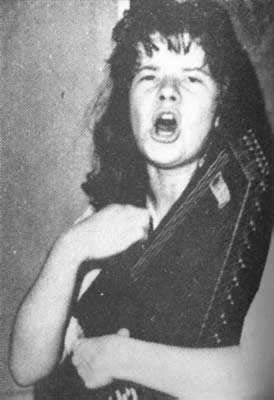

Janis in Austin '62 & '66

From Threadgill's to Monterrey Pop, Joplin became the first true female rock star

To be a high school beatnik in 1960 in Port Arthur, Tex. is to set yourself up for a rough time. But Janis Joplin had made up her mind that she was going to live life her way, damn the small-minded. She discovered the blues at a time when blacks and whites couldn’t eat at the same restaurants in Texas. She read Kerouac and Ferlinghetti in a blue collar town that looked at non-required reading with suspicion. “Men liked to pick on Janis,” said Powell St. John, her former bandmate in the Austin-based Waller Creek Boys.

Joplin spent time in Austin at two junctures in her development as a singer- in 1962, when she attended UT and sang at Threadgill’s, and in early ‘66, when she played the 11th Door and restarted a career with the shriek of Roky Erickson in mind.

“She Dares To Be Different” was the headline of the story written about Janis in 1962, when she was an autoharp-toting folk singer at the University of Texas. The “enviously unrestrained” 19-year-old wore dungarees and went barefoot when other coeds wore dresses or skirts and blouses. But her standing out came at a price, with the unrelentless bullying scarring her, St. John said. “You’re better than them,” he told her, when she cried after a fraternity named her “Ugliest Man On Campus.” Then why are they winning?

Singing was her sanctuary. Janis was born with a powerful voice that could take her where her instincts led, but she didn’t find out until she was about 16 and discovered 1920’s blues queen Bessie Smith. “Love oh love oh careless love,” Janis harmonized and then took the lead on “You’ve made me break a many true vow, then you set my very soul on fire.” Janis’s friends were knocked out. “You sing as good as that lady on the record!”

At that moment her life became about something bigger than P.A.

She displayed advanced intelligence early, skipping second grade, but Janis was a bored C student as a teenager. Her real education came through her small circle of fellow freaks, including Grant Lyons, a record collector who turned her onto Leadbelly and Woody Guthrie. From there she found Odetta and Bessie and Big Mama Thornton and Jean Ritchie. Appalachian folklorist Ritchie sang a repertoire of over 300 songs and Joplin set out to learn every one.

“Whenever Lanny (banjoist Wiggins) and I would suggest a song, Janis would know two others just like it,” St. John said of the earliest get-togethers of Joplin’s first band. “She was always a great singer, understanding the finer points of getting a song across.” Besides Threadgill’s, the Waller Creek Boys played the weekly “folk sings” at the Texas Union, sometimes in a reserved room, sometimes in the Chuck Wagon (which would later become the Cactus Cafe.)

During Joplin’s Port Arthur years, there were frequent 30-mile trips to Vinton, LA, where you could drink at 18 (if they even checked ID). This is where Janis developed her din-knifing cackle. Janis and her friends would party to Jerry LaCroix and the Counts at Buster’s or Lou Ann’s, getting a crash course in soulful American music. A proximity to Louisiana and the Gulf Coast ensured that the Golden Triangle (Beaumont-Orange-Port Arthur) would have a steady supply of roots-reared musicians. But the folk scene was non-existent.

This is where Austin came in. After a secret overnight trip to the mythical liberal outpost, and finding a song-swap at “the Ghetto,” on Nueces St. near Dirty’s, still going at 4 a.m., Janis decided to enroll at UT. She had found her people in Texas. And the state capital had never seen, or heard, anything like Janis.

As Pat Sharpe wrote in that 1962 profile in the Daily Texan: “Janis sings with a certain spontaneity and gusto that cultivated voices sometimes find difficult to capture.” Kenneth Threadgill, a veteran country singer, spotted right away that Janis was special. One night he gave Janis free beer NOT to sing, but that was less an insult than an acknowledgement that he didn’t want to follow her.

Love made Janis different, she was a junkie for it- giving and receiving. That’s why she stayed so close to her parents, even though they fought bitterly as she became a young woman. She knew their love was real, uninfluenced by who she had become. Even as she did hard drugs and kept Southern Comfort in business, she wrote letters home almost daily.

Courage and insecurity were the oversized lenses through which Janis saw the world, at least from the last half of her 27 years. The rebel side came at about age 14, when Janis realized she’d never be one of the pretty girls, the popular girls at Thomas Jefferson High School. Before that, she’d lived a fairly idyllic life, according to all the bios. Her father Seth had a good job with Texaco.

But Joplin built a tough exterior on her days growing up in the sulphur-smelling city of 66,600, whose slogan was “We Oil the World.”

Janis was “from good pioneer stock” she’d say, explaining her ability to handle drugs and alcohol. But she was easily pushed to the emotional breaking point. It was that mix of strength and vulnerability that came through in her singing. The first female rock star, her performances were spirit revivals, with pain and possession doing a cathartic dance. Until the punk explosion of the ‘70s, no white singer was so brilliantly unhappy.

The Janis Joplin heroin overdose death at age 27 is a tragedy told in several books and on the screen. We know about her substance abuse problems and we’ve seen her sensational breakout at Monterrey in ’67, as she donned gold lame’ and transformed into “Pearl.”

But nobody talks much about the moment of musical catharsis in Austin on March 13, 1966. She came to the Methodist Student Center on Guadalupe as a folk/blues singer and left with a soul full of rock n’ roll. Three months later, she was living in San Francisco as the lead singer of Big Brother and the Holding Company.

That show in Austin was the only time Joplin shared the stage with the 13th Floor Elevators, who were two months from the national release of debut single “You’re Gonna Miss Me.” The concert was organized by Joplin’s Jefferson High classmate Tary Owens as a benefit for ailing East Austin fiddler Teodar “Papa T” Jackson, but he passed away a few days earlier so money raised went to bury him.

This was during a sober period for Janis- who’d been bused home from San Francisco as an 88-lb speedfreak in May ’65. But after Austin American Statesman music columnist Jim Langdon, also from Port Arthur, called her “the best white blues singer in America,” Joplin started performing again at Bill Simonson’s 11th Door on Red River.

At the Papa T benefit, she wore a dress with her hair up and belted four blues songs- “Codine,” “I Ain’t Gonna Worry,” “Going Down to Brownsville” and “Turtle Blues”- accompanied only by her guitar. Janis got a huge response from the 400 on hand, then watched the 13th Floor Elevators levitate the crowd.

Janis played one more concert in town as a blues singer, with pianist Robert Shaw at the “Barrelhouse and Blues” show at the Texas Union Ballroom on May 5, 1966. But soon after, fellow UT dropout Chet Helms, with whom she’d hitchhiked to S.F. in Jan. 1963, beckoned her to return to the Bay Area. In the year since Greyhound had an intervention for Janis, Helms and his Family Dog company started booking the earliest hippie concerts in S. F. at the Avalon Ballroom. He had started managing a band he named Big Brother and the Holding Company and wanted Joplin to be the singer.

But Janis was terrified of getting back into the drug scene of California. She had been doing well, going back to school at Lamar University to study anthropology and working in an office. Her family cursed Langdon for encouraging Janis to pursue a music career.

It didn’t take much arm-twisting, though. Janis was ready to enter the rock arena.

She told her family she was going to Austin for a few days, but on June 6, 1966, the day she officially joined Big Brother, she sent them a letter saying she was actually in S.F. “My old friend Chet is now ‘Mr. Big’ in San Francisco,” she wrote. “And the whole town has gone rock n’ roll.”

Janis Joplin became a big star, but three years after Monterrey, she was dead. Her last appearance in Austin was at a “Jubilee” for her earliest mentor Kenneth Threadgill at the Party Barn in Oak Hill in July 1970, three months before her passing. She sang a song she’d not yet recorded called “Me and Bobby McGee” and another Kris Kristofferson song “Sunday Morning Coming Down.” An expected crowd of 500 grew to 5,000 when word got out that Janis was in town and had planned to attend.

Earlier in 1970, Joplin heard that Bessie Smith, her earliest inspiration, did not have a gravestone. Joplin paid for one, with the inscription reading, “The Greatest Blues Singer In the World Will Never Stop Singing.”

MORE READING

“She Dares to Be Different,” Pat Sharpe’s July 27, 1962 article on Janis Joplin

Kenneth Threadgill was much more than Janis’s mentor in a bar apron.

Was looking for your story about Dylan and The Band's first show being in Austin to post this suggestion but didn't see it, so it's out of place but at least in similar time period.. Am a Dylan nerd and long time appreciator of your articles and am looking forward to your Austin music history book's release. Thanks for sharing the chapter portions.. I've mentioned several to some of my long-time Austin friends who are also looking forward to it...

Here's a suggested tidbit for your consideration as possible book inclusion in case you were unaware and it's not too late and it may be useful. I just heard Dylan's interview with Detroit DJ of WDTM Radio on Oct 24 1965. About 12:24, they're talking about all the crowds where half bood or walked out etc, Dylan credits the Austin (and Dallas) audiences as being only ones he's aware of where he knows that they received a strongly enthusiastic and positive reaction from audience. He describes getting a strong feeling that audience "got it" and could appreciate what he and band were doing because they understood the feeling behind what they were doing. He recounts "they clapped and went crazy after every verse" of Just Like Tome Thumbs Blues.

A unique aspect of the interview is Dylan being unusually open and cooperative with interviewer Alan Stone. A few things seem to explain Dylan giving unusually detailed and thoughtful answers and overall cooperation during the 19 minute interview before their sound check/rehearsal. As he mentions, he was of the only DJ's in Detroit that regularly played the first several Dylan records. He had interviewed Dylan a year earlier while still a solo artist and not yet the pop star he currently was, so they'd met and Dylan seemed to trust him. He was well prepared with well thought out questions and respectful to Dylan and his work throughout. And, last but not least, as he mentions in his humble understatement of a comment after pointing out to whoever posted it to YouTube that they misspelled his name, says "Bob insisted we share a bottle of wine before the interview, but it still worked."

Am guessing you may have checked when you wrote the piece about the Austin '65 Dylan & lineup that became the band's first show, but if it's possible to find anyone that was actually at that Austin show and remembers details of it, or a review that mentions details of show, I think it would be interesting to get any recollection they may have of the audience's reaction and specifically clapping after every verse of Tom Thumb's Blues and if they sensed same thing Dylan did about audience "getting it". Just Dylan crediting the Austin audience the way he does in this interview is pretty cool and interesting itself. And coming from Dylan at the time, a big compliment in my opinion.

Transcription of Austin audience related comments from 12:24 into interview: "I'll tell you. It's like it's more like we only played one place so far where I know, I had this very powerful feeling, and that's in Dallas Texas you know and in Austin Texas.. We played concerts down there and we played Tom Thumb's Blues it's called..I don't know if you're acquainted with it or not?..Yes. They knew the feeling, you know what it was all about you know and they clapped after every verse and went wild you know. I mean they really knew. They may not have known exactly maybe what it was all about but they knew the feeling of it. They're very close to the whole Mexican color and everything down there you know and it's the way things feel.."

Link to misspelled "Bob Dylan Allen Stone Interview": https://youtu.be/YB2hmVDErAg?t=742

I have wondered whether Teodar Jackson was related to Stonewall Jackson of the Capital City Quartet. Cactus Pryor told me that as a youth he saw Stonewall perform and viewed him as something as a role model. Stonewall sang bass, Cactus baritone.