Owed to Liberty Lunch 1975-1999

Watch the musical slideshow of Bill Leissner's Lunch documentation

To those of us who moved to Austin in the ’80s and had to hear about how we missed all those amazing ’70s clubs, think of how much worse that would have been if we didn’t have our own AWHQ in Liberty Lunch. But this sacred venue also had a date with the ‘dozer, wiped away in 1999 to make room for Computer Sciences Corporation headquarters. The bare-boned venue’s demise was determined by two words: city owned. The rent in this prime downtown location was only $600 a month, so the Lunch’s days were numbered. For twenty-four years!

Shows were general admission, and we all had our favorite Lunch spot: mine was stage right, six paces back, where the pot smoke from the patio hit the jet stream of sound. The least favorite doorman in the Little Town With the Big Guest List was the guy named David who used to perform weird folk as Blanche. Parked at the Lunch entrance, stone-faced as a Palace guard, he couldn’t quite mask delight when he made someone from the Austin Chronicle pay cover. (Bands loved him.)

Physically, there wasn’t much to the room that used to store lumber. No place to sit. No place to shit, at least in private. When pre-show adrenaline loosened the bowels, acts had to use the gross prison bathrooms because there wasn’t running water backstage. “Are you going to play ‘Stinkpot?’ a fan asked a stall-less, squatting member of Soulhat one night. “I’m playing it now.” (That anecdote came from Chris Riemenschneider on a piece we co-wrote for the Statesman on the Lunch’s demise. I tell you that now because I had to cut Riemenschneider’s credit from the book due to length.)

What made this Lunch so fulfilling was the ever-smiling staff, who got their reward when audience members mouthed “thank you” with a hand on their heart on the way out.

You felt safe at Liberty Lunch, which was all-ages, so many parents just dropped their kids off so they could go out for a quiet dinner—or home for loud sex.

Besides great roadshows, like the February ’92 triplet of Dinosaur Jr., My Bloody Valentine, and Babes in Toyland (Christmas for audiologists!), the Lunch nurtured several local scenes, including funk-rap with Bad Mutha Goose, Do Dat, Bouffant Jellyfish, and Retarted Elf. Any kind of live dance music worked there. Any kind of music really.

“I always thought of it as the Willie Nelson of Austin venues, that one infallible place,” said David Garza, who sold out the Lunch with Twang Twang Shock-a-Boom in 1990. When he left the group, prematurely it seemed, only a hundred showed up for his first solo gig at 405 W. 2nd Street. “Lunch don’t lie,” he laughed.

On a dead night—and there were more of them than Nevilles in New Orleans—the room was so big that it was kind of embarrassing for everyone. But a great night, like when Bonnie Raitt jammed with the Meters, or when Ween played for four inspired hours, or when Replacement fans burned Austin Chronicles in a trash can for heat, was hitting the nightlife jackpot.

Mark Pratz and Jeanette Ward, now married, ran things from ’83- ’99, but let’s not forget the Austin couple that founded Liberty Lunch. Before Esther’s Follies, former UT drama students Shannon Sedwick and Michael Shelton took over the site of a former Calcasieu lumberyard on December 9, 1975. They planned to call this food/ performance space Progressive Grocery, but while scraping the paint off the front of the building they saw the name Liberty Lunch from when the smaller, enclosed room was a café in the ’50s owned by a blind man, Harold Carlson. With the upcoming bicentennial patriotism of 1976, Liberty Lunch was the perfect name.

With chef Emil Vogley, the club’s Cajun-flavored restaurant got a rave in Texas Monthly soon after opening, but the staff was overwhelmed by the demand. The first Liberty Lunch reputation was for excruciatingly slow service. But the music and the beer in the big, open-air space next door gradually took over, with exotic local bands Beto y Los Fairlanes (salsa), the Lotions (reggae), and Steam Heat (funk), inspiring dancing on the pea gravel floor that created dust storms. This was around when Doug Jacques painted that trippy-dippy tropical mural, which especially seemed out of place years later at GWAR.

The city wanted to shut down Liberty Lunch and all those half-naked stoned hippies almost from the very beginning. “Liberty Lunch has always been a point of contention with the city,” said Sedwick. But something cool was happening. And pro-bono lawyers like to dance, too.

After Sedwick and Shelton left in ‘78 to concentrate on Esther’s Pool (at the current Flamingo Cantina location), and the new Buffalo Grille (1116 W. Sixth), Charlie Tesar took over. After constant rain canceled shows in the summer of ’81, they built a roof over the Lunch with girders, trusses, and beams bought from the razed Armadillo. Back doorman Dale Watkins was another continuation. The torch had been passed, but the old Lunch crowd hated it not being alfresco. Austin was so much cooler before roofs.

Pratz graduated from doorman to booker in ’81, then joined with Louis Meyers, manager of Killer Bees, to form Lunch Money Productions two years later. Reggae, African juju music, and, of course, the Neville Brothers from New Orleans, did especially well. Burning Spear would sell out every time.

Sundays were reserved for benefits, with Pratz joking with John Kelso that the Lunch helped just about everyone besides Nuke the Whales.

By the late ‘80s, the 1,100-capacity Lunch was the perfect launching pad for breakout bands like Nirvana, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Green Day, Oasis, Foo Fighters, Beck, Pavement, and Alanis Morrissette, too big for the Continental Club, which Lunch Money also booked. You’d see k.d. lang, when she was a rockabilly singer, and then the next night would be Black Flag and then the Count Basie Orchestra.

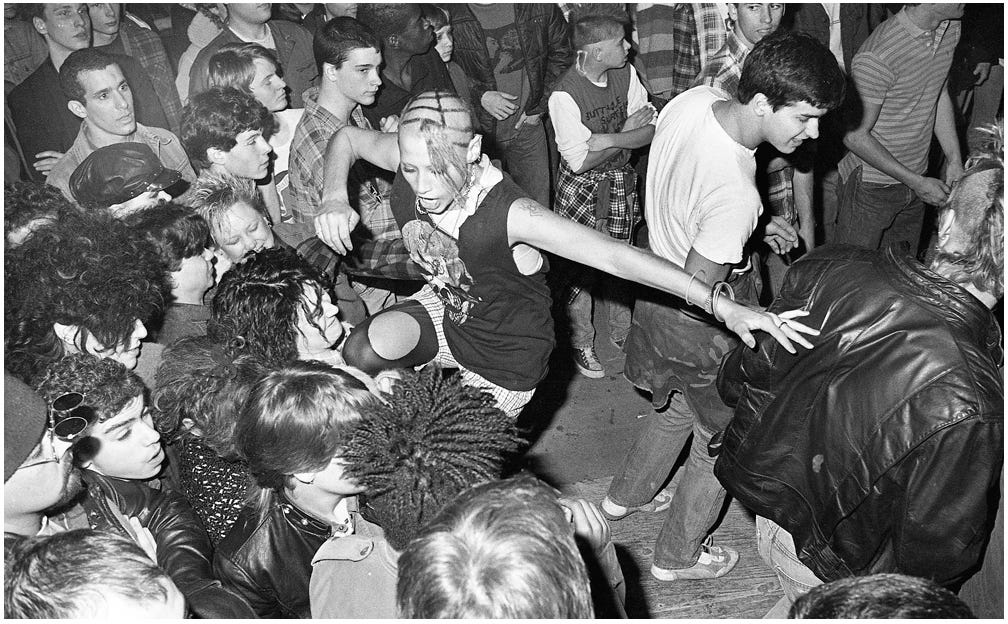

Stage-diving was a constant distraction at punk shows, but Fugazi had a brilliant solution when they made their Austin debut, opening for Bad Mutha Goose, at the Lunch in May 1989. Ian MacKaye announced that anyone from the audience that jumped on the stage would get a kiss on the mouth. The set started, and some young punk still thinking Minor Threat, got on stage and started his leap into the crowd. But MacKaye tackled him, somebody held him down while, for all the audience to see, MacKaye planted a big kiss on the kid’s mouth. Homophobia killed stage-diving at Fugazi. For at least half an hour.

In 1998, the City Council voted to end the Lunch lease and rent the land to a high-tech company. Mayor Kirk Watson pushed for it, based on an expanded tax base. In December of that year, the Greg Dulli incident happened.

After an Afghan Whigs show, the singer got into a fight with a stagehand, was knocked out, and hit the back of his head on the concrete floor, which sent him to Brackenridge with a fractured skull. His lawsuit against the Lunch was eventually dropped, but the club got a black eye in the national music press, with bands vowing to never play there again. Though witnesses said Dulli was the instigator, the p.r. blemish cleared the way for Watson’s wrecking crew. Liberty Lunch was leveled eight months later.

It was only a building, and a homely one at that, but for over two decades Liberty Lunch was a structure where musicians and fans were at their best, because on a good night it couldn’t get any better.

G-L-O-R-I-A-thon

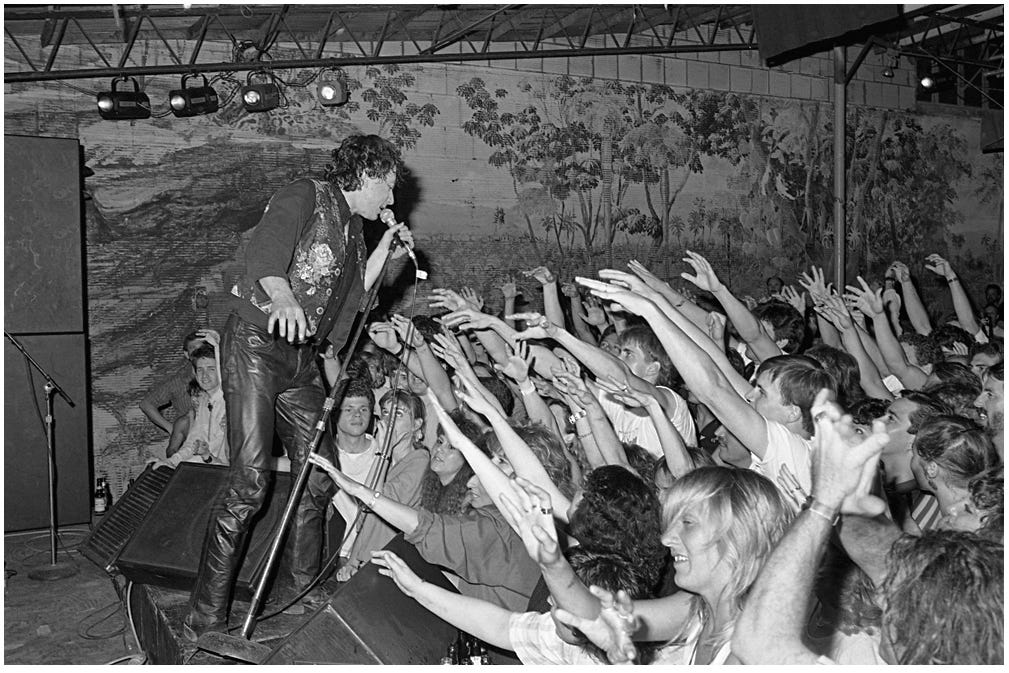

The venue’s perfect swan song came in July 1999, when Michael Hall of the Wild Seeds (and Texas Monthly) had the ridiculous idea of enlisting Austin musicians to keep playing “Gloria” by Them for 24 hours continuously. Who’s going to play at 5 a.m? Or two in the afternoon?

One of Hall’s short-lived bands the Brooders started the one-song marathon at 9 p.m. Friday July 23, kicking it off in a trance of vibrato guitars for 15 minutes. And then Hall started singing those lines that launched 10,000 bands; “She comes ‘round here…” It was another forty-five minutes until the chorus was reached like a climax. “G-L-O-R-I-A, Gloria!” Twenty-three more hours to go.

The Austin music scene showed up like they do. All night, all day. Jam bands, blues players, shuffle drummers, and sax players. (One thing you’ll never see on eBay is a “Gloriathon” bootleg.)

At about three in the afternoon, Van Morrison’s road manager held up a phone as Van the Man sang “Gloria” at a festival in Scotland, and it was piped over the sound system at the Lunch. He didn’t normally perform the 1965 song anymore, Morrison said, but there were a crazy bunch of folks in Austin, Texas playing “Gloria” for twenty-four hours straight, so he dedicated it to them.

A great moment, for sure, but the superstar cameo was a deviation of what was really happening. We were not just toasting a beloved venue and the people who made it shine. We were saying goodbye to a paradise of our youth, a time and place that made us feel as if we finally belonged. The summer of ’99 marked the end of the ’70s and ’80s in Austin. It was time to start families, to get on with the work that would define us, to see what we were really made of now that the fantasy was being torn down.

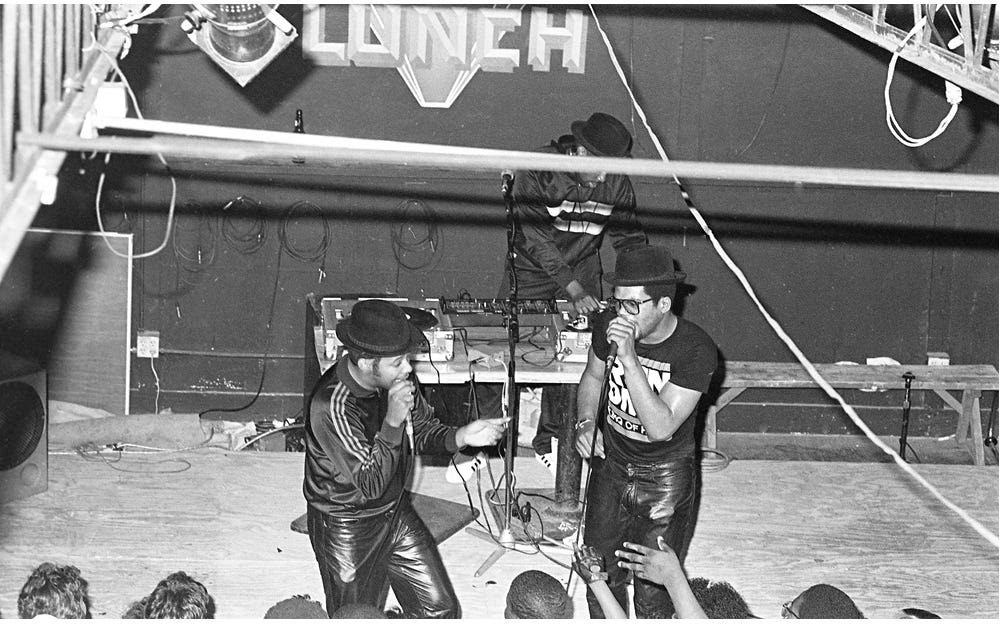

HISTORIC NIGHT: RUN-DMC USHERS IN RAP AGE ON JUNETEENTH

The first rap concert in Austin was the last one at Municipal Auditorium before it became Palmer. A package show featuring Sugarhill Gang, Grandmaster Flash, Funky Four Plus One and the bands Kano and Skyy drew 3,000 fans on April 1, 1981. “We’re not a band,” Flash announced during his set with the Furious Five. “We’re seven guys and two turntables.” Since this show was just eighteen months after the first hip hop record “Rapper’s Delight,” Austin was in on the underground sensation relatively early on. But four years later, Madonna’s crowd hated her opening act at the Erwin Center, lustily booing the Beastie Boys on May 5, 1985. But the whiny, bratty Beasties were pretty terrible back then.

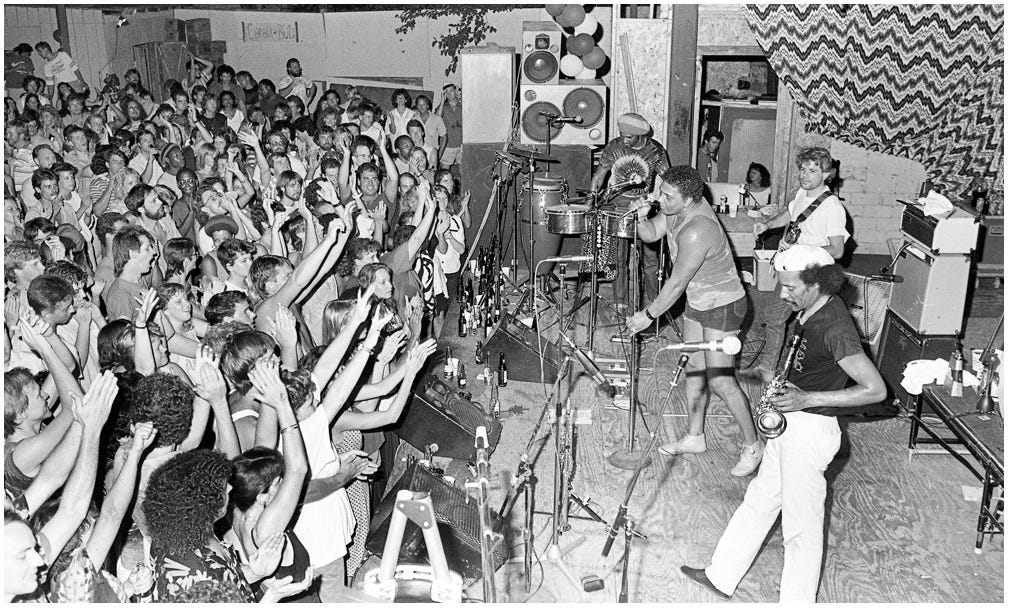

The golden era of hip-hop introduced itself to Austin audiences six weeks later when Run-DMC played a delirious Juneteenth show at Liberty Lunch. This was a year before Raising Hell and its Aerosmith collab on “Walk This Way” drew down the bridge between rock and rap, but Run-DMC had already become the first hip hop act to record a million-selling LP with King of Rock. Joseph “Run” Simmons, Darryl McDaniel and Jam Master Jay played Austin on a day off from the Fresh Festival package tour, which they headlined. They were hotter’n hell!

So it must’ve seemed strange when Harold McMillan of the sponsoring Black Arts Alliance picked up the trio at Robert Mueller Airport in his beat-up Datsun B-210 and took them to the seedy Stars Inn Motel on I-35 near 32nd Street. “They were saying ‘Hey, man, this ain’t in our rider,’ but I had to tell them we were just a broke black arts organization,” McMillan recalled. The BAA paid Run-DMC $5,000 and ended up making a profit of $6,000 on the $10 show.

McMillan’s Datsun with the holes in the floorboard wasn’t the only low ride the rap icons took during their twenty-four hours in Austin. When they showed up at Liberty Lunch before the show, they realized that they’d left their records on their Fresh Fest tour bus and enlisted co-promoter Louis Meyers to take them to the record store, pronto. Meyers drove them to Sound Warehouse on Burnet Road so they could buy vinyl to rap over. “They just climbed in the back of the pickup and we were off,” said Meyers.

The sold-out crowd was about 50-50 Black and white—unheard of in Austin at the time—and they were united in ecstasy when Run-DMC charged out onto the stage. Only problem was that the plywood Liberty Lunch stage had some play in it and every time one of the rappers jumped or even stepped hard, the record would skip. Jay was doing his best to keep the beat going, but it soon became apparent that the only way to save the show was for Run and DMC to be as stationary as possible. They did a lot of that folding arm pose.

It was a thrown-together benefit, but the Run-DMC show is significant for validating hip hop as a live music event to the rock crowd. This wasn’t held at some dance club on Sixth Street, but the proving grounds of Liberty Lunch. Back in 1985, people still didn’t know if rap was more than a fad. But when you felt the power of Run-DMC live, you knew it had the legs of a Kenyan.

(Photo of Mark and J-Net by Dayna Blackwell).

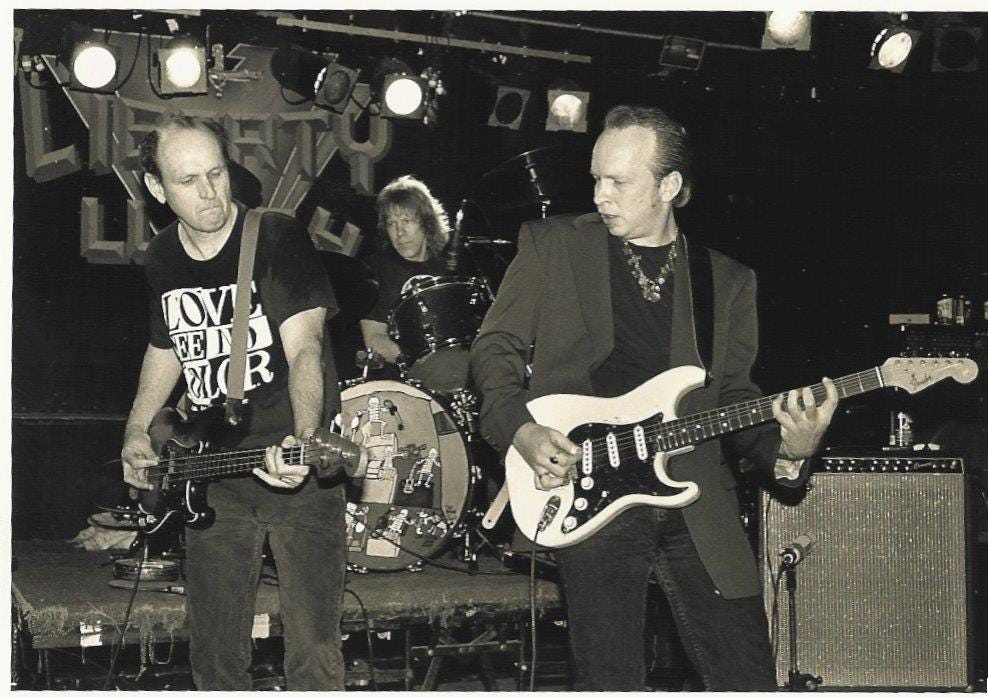

Hub City Movers played our last reunion at Liberty Lunch in October 1985. Mark (and we) were hoping for a bigger turnout. Only other time I was there was next to last time I've seen Buddy Guy (https://technologists.com/privatemp3s/images/20231018_bulletinboardStormBuddy.jpg)

A shame we can't figure out a way to invest in our music venues somehow. Eventually there will not be any live music in central Austin and then what will be the point of living here? Just another city at that point.